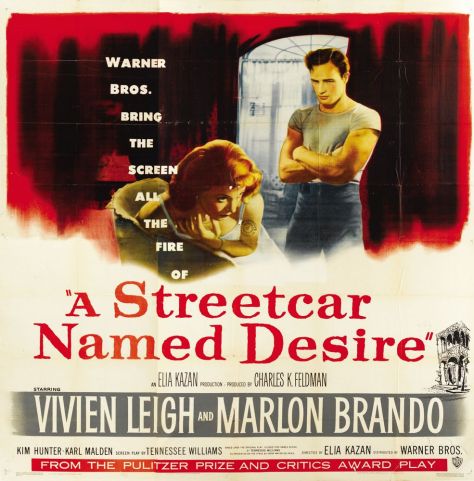

Vivien Leigh and Marlon Brando star in Elia Kazan’s acclaimed adaptation of Tennessee Williams’ landmark play – back in UK cinemas from 7 February.

Vivien Leigh and Marlon Brando star in Elia Kazan’s acclaimed adaptation of Tennessee Williams’ landmark play – back in UK cinemas from 7 February.

Occupying a railway arch in London’s buzzing Flat Iron Square, Bar Douro was created as a way to bring authentic Portuguese food to London. With ties to Portugal traced back through the family, Bar Douro has matched exquisite Portuguese wines with all the tradition of local Portuguese food. The atmospheric 30-cover marble counter-top dining space offers an intimate window to the best of Portuguese culinary heritage.

When designer Richard Found discovered the dream plot on which to build his serene contemporary retreat overlooking a lake, he didn’t bet on what happened next. In the grounds stood a derelict 18th-century gamekeeper’s cottage, which was immediately spot-listed by Historic England. “It changed the whole dynamic of what I thought would be a straightforward new-build project, and became a far more arduous planning exercise.”…

House Proud is a series of videos created by the Telegraph which showcase some of Britain’s most idiosyncratic, quirky, unusual and unforgettable homes. A celebration of British eccentricity and imagination, in each film the owner gives us an intimate guided tour and tells us the story of their unique property.

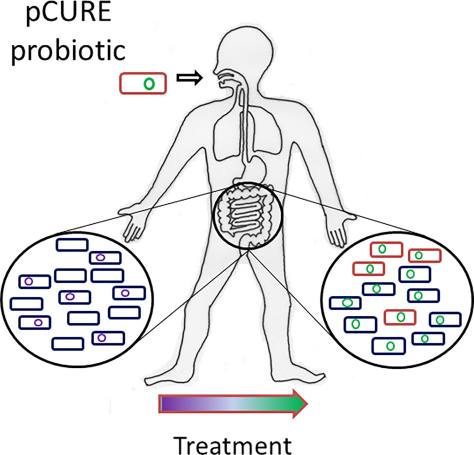

From a Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News online article:

“We were able to show that if you can stop the plasmid from replicating, then most of the bacteria lose the plasmid as the bacteria grow and divide. This means that infections that might otherwise be hard to control, even with the most powerful antibiotics available, are more likely to be treatable with standard antibiotics.”

“We were able to show that if you can stop the plasmid from replicating, then most of the bacteria lose the plasmid as the bacteria grow and divide. This means that infections that might otherwise be hard to control, even with the most powerful antibiotics available, are more likely to be treatable with standard antibiotics.”

Researchers headed by a team at the University of Birmingham in the U.K. have developed a probiotic drink containing genetic elements that are designed to thwart antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in gut bacteria at the genetic level. The drink targets small DNA elements called plasmids that carry antibiotic resistance genes, and which are able to replicate independently and spread between bacteria. By preventing these plasmids from replicating, the antibiotic resistance genes are displaced, effectively resensitizing the bacteria to antibiotics.

In GQ’s on-going quest to road test the contenders for the 2020 Car Awards, chef Paul Ainsworth takes a trip down memory lane in a brand new old-school British roadster.

The winners of the Car Awards, in association with Michelin, will be revealed on 3 February, 2020. Full coverage will appear in the March issue of GQ, on sale 6 February. For more information visit: GQ.co.uk

In a new film released as part of Cambridge University’s focus on Sustainable Earth, Dr Jane Goodall DBE talks about the environmental crisis and her reasons for hope. “Every single day that we live, we make some impact on the planet. We have a choice as to what kind of impact that is.”

At the age of 26, Jane Goodall travelled from England to what is now Tanzania, Africa, and ventured into the little-known world of wild chimpanzees. Among her many discoveries, perhaps the greatest was that chimpanzees make and use tools. She completed a PhD at Newnham College in Cambridge in 1966, and subsequently founded the Jane Goodall Institute in 1977 to continue her conservation work and the youth service programme Roots & Shoots in 1991.

She now travels the world as a UN Messenger of Peace. “The human spirit is indomitable. Throughout my life, I’ve met so many incredible people – men and women who tackle what seems impossible and won’t give up until they succeed. With our intellect and our determined spirit, and with the tools that we have now, we can find a way to a better future.”

Cambridge University’s focus on Sustainable Earth looks at how we transition to a carbon zero future, protect the planet’s resources, reduce waste and build resilience.

Lionel Shriver (born Margaret Ann Shriver; May 18, 1957) is an American journalist and author who lives in the United Kingdom. She is best known for her novel We Need to Talk About Kevin, which won the Orange Prize for Fiction in 2005 and was adapted into the 2011 film of the same name, starring Tilda Swinton.

Shriver has written for The Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times, The New York Times, The Economist, contributed to the Radio Ulster program Talkback and many other publications. In July 2005, Shriver began writing a column for The Guardian, in which she has shared her opinions on maternal disposition within Western society, the pettiness of British government authorities, and the importance of libraries (she plans to will whatever assets remain at her death to the Belfast Library Board, out of whose libraries she checked many books when she lived in Northern Ireland). She currently writes regularly for The Spectator.

In online articles, she discusses in detail her love of books and plans to leave a legacy to the Belfast Education and Library Board.

From Wikipedia

London – For Tullio Crali (1910-2000) Futurism was not just a school of painting, but an attitude to life itself. Reflecting the movement’s enthusiasm for the modern world, his imagery embraced technology and the machine as important sources of creative inspiration. However, with its particular focus on “the immense visual and sensory drama of flight”, Crali’s work is most closely associated with the genre of ‘aeropainting’, which dominated Futurist research during the 1930s.

London – For Tullio Crali (1910-2000) Futurism was not just a school of painting, but an attitude to life itself. Reflecting the movement’s enthusiasm for the modern world, his imagery embraced technology and the machine as important sources of creative inspiration. However, with its particular focus on “the immense visual and sensory drama of flight”, Crali’s work is most closely associated with the genre of ‘aeropainting’, which dominated Futurist research during the 1930s.

Crali discovered Futurism when he was just fifteen years old. An immediate convert, he officially joined the movement in 1929 and quickly developed his own distinctive interpretation of its artistic principles. Despite incorporating recognisable details such as clouds, wings and propellers, Crali’s thrilling

imagery challenged conventional notions of realism by means of its dynamic perspectives, simultaneous viewpoints and powerful combination of both figurative and abstract elements.

As a result of his talent, versatility and unshakable commitment to Futurist ideas, Crali swiftly became one of the movement’s key representatives. He continued to be its staunchest advocate during the post-war era, remaining faithful to Futurism’s aesthetic tenets throughout his life.

Featuring rarely seen works from the 1920s to the 1980s, this exhilarating exhibition covers every phase of the artist’s remarkably coherent career, including iconic aeropaintings, experimental works of visual poetry and mixed-media reliefs, as well as examples of ‘cosmic’ imagery dating from the 1960s, inspired by advances in space exploration. Also featured are a large number of Crali’s famous Sassintesi: enigmatic compositions of stone and rock, ‘sculpted’ by natural forces.

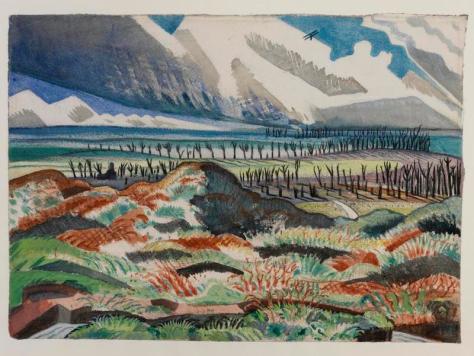

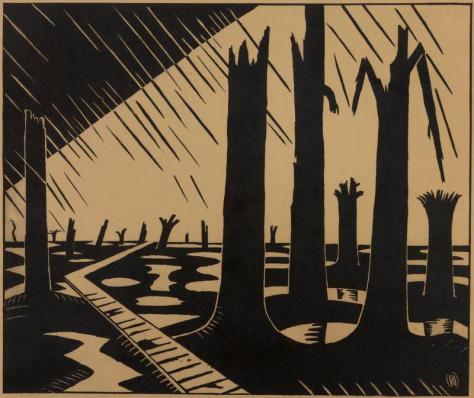

Paul Nash (11 May 1889 – 11 July 1946) was a British Surrealist painter and war artist, as well as a photographer, writer and designer of applied art. Nash was among the most important landscape artists of the first half of the twentieth century. He played a key role in the development of Modernism in English art.

Born in London, Nash grew up in Buckinghamshire where he developed a love of the landscape. He entered the Slade School of Art but was poor at figure drawing and concentrated on landscape painting. Nash found much inspiration in landscapes with elements of ancient history, such as burial mounds, Iron Age hill forts such as Wittenham Clumps and the standing stones at Avebury in Wiltshire. The artworks he produced during World War I are among the most iconic images of the conflict. After the war Nash continued to focus on landscape painting, originally in a formalized, decorative style but, throughout the 1930s, in an increasingly abstract and surreal manner. In his paintings he often placed everyday objects into a landscape to give them a new identity and symbolism.

Official World War I Artist – In November 1917 Nash returned to the Ypres Salient as a uniformed observer with a batman and chauffeur. At this point the Third Battle of Ypres was three months old and Nash himself frequently came under shellfire after arriving in Flanders. The winter landscape he found was very different from the one he had last seen in spring. The system of ditches, small canals and dykes which usually drained the Ypres landscape had been all but destroyed by the constant shellfire. Months of incessant rain had led to widespread flooding and mile upon mile of deep mud. Nash was outraged at this desecration of nature. He believed the landscape was no longer capable of supporting life nor could it recover when spring came. Nash quickly grew angry and disillusioned with the war and made this clear in letters written to his wife. One such written, after a pointless meeting at Brigade HQ, on 16 November 1917 stands out,

I have just returned, last night from a visit to Brigade Headquarters up the line and I shall not forget it as long as I live. I have seen the most frightful nightmere of a country more conceived by Dante or Poe than by nature, unspeakable, utterly indescribable. In the fifteen drawings I have made I may give you some idea of its horror, but only being in it and of it can ever make you sensible of its dreadful nature and of what our men in France have to face. We all have a vague notion of the terrors of a battle, and can conjure up with the aid of some of the more inspired war correspondents and the pictures in the Daily Mirror some vision of battlefield; but no pen or drawing can convey this country—the normal setting of the battles taking place day and night, month after month. Evil and the incarnate fiend alone can be master of this war, and no glimmer of God’s hand is seen anywhere. Sunset and sunrise are blasphemous, they are mockeries to man, only the black rain out of the bruised and swollen clouds all though the bitter black night is fit atmosphere in such a land. The rain drives on, the stinking mud becomes more evilly yellow, the shell holes fill up with green-white water, the roads and tracks are covered in inches of slime, the black dying trees ooze and sweat and the shells never cease. They alone plunge overhead, tearing away the rotting tree stumps, breaking the plank roads, striking down horses and mules, annihilating, maiming, maddening, they plunge into the grave, and cast up on it the poor dead. It is unspeakable, godless, hopeless. I am no longer an artist interested and curious, I am a messenger who will bring back word from the men who are fighting to those who want the war to go on for ever. Feeble, inarticulate, will be my message, but it will have a bitter truth, and may it burn their lousy souls.”

Nash’s anger was a great creative stimulus which led him to produce up to a dozen drawings a day. He worked in a frenzy of activity and took great risks to get as close as possible to the frontline trenches. Despite the dangers and hardship, when the opportunity came to extend his visit by a week and work for the Canadians in the Vimy sector, Nash jumped at the chance. He eventually returned to England on 7 December 1917.

From Wikipedia

Electric planes could soon fly commuters from city to city, a transport minister has disclosed. George Freeman, minister for transport and innovation, told The Telegraph’s “Chopper’s Brexit Podcast” that there was “a whole opportunity for short-haul transport at low altitude” that the country was yet to grasp.

In an episode of 2020 predictions, Mr Freeman said: “This will be the year where we begin to see a whole new world of low level aviation, Velocopters, electric planes. We already run the world’s first commercial electric plane service and Boris and I have been looking at how we can develop UK leadership in electric plane technology.” Mr Freeman said the planes could take eight passengers and fly at 2,500ft and could be used for “short hops between cities that take you an hour or two in the car, pumping out carbon monoxide.”

“At the moment the electric plane seats eight. But you know what the aerospace industry is like – eight soon becomes 18, and that soon becomes 28. We are determined to lead in the revolution of clean transport.”

To listen to the podcast in full, head here: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/politics/…