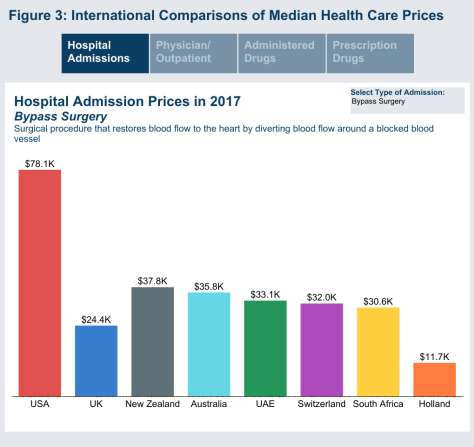

From Health Care Cost Institute (HCCI) online release (12/17/19):

Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) is one of the world’s most loved artists. His paintings, drawings and letters inspire people of all ages. His work can be admired in numerous museums around the world. Many places where the artist lived and worked can be visited, from the Netherlands to the South of France. About 25 organisations and museums in the Netherlands, Belgium and France have joined forces under the name Van Gogh Europe. Together they are actively engaged in maintaining and promoting Van Gogh’s heritage.

Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) is one of the world’s most loved artists. His paintings, drawings and letters inspire people of all ages. His work can be admired in numerous museums around the world. Many places where the artist lived and worked can be visited, from the Netherlands to the South of France. About 25 organisations and museums in the Netherlands, Belgium and France have joined forces under the name Van Gogh Europe. Together they are actively engaged in maintaining and promoting Van Gogh’s heritage.

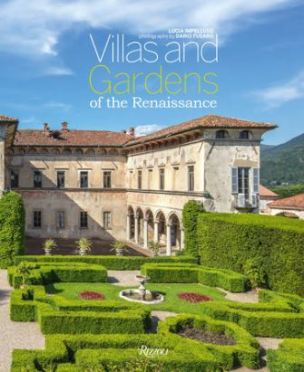

An historical text introduces each property, giving an overview of its origins. The villas have been specially photographed for this book by Dario Fusaro, with views of both the palace interiors and their grounds, as well as the gardens, glimpses of the halls, details of the furnishings, and a focus on the frescoes, where still preserved. Explanatory text offers insights on the most

An historical text introduces each property, giving an overview of its origins. The villas have been specially photographed for this book by Dario Fusaro, with views of both the palace interiors and their grounds, as well as the gardens, glimpses of the halls, details of the furnishings, and a focus on the frescoes, where still preserved. Explanatory text offers insights on the most  interesting frescoes, such as those of Veronese at Villa Barbaro. For the first time, Fusaro also employs a drone with the purpose of capturing the architectural structure and elements of each Italian Renaissance garden, from above and as a whole.

interesting frescoes, such as those of Veronese at Villa Barbaro. For the first time, Fusaro also employs a drone with the purpose of capturing the architectural structure and elements of each Italian Renaissance garden, from above and as a whole.

A stunning collection of photographs celebrating the excellence of the Italian Renaissance period through palaces and gardens built between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

The book illustrates nine locations of extraordinary artistic and architectural interest, conceived by prominent Italian families and dynasties as urban villas or country houses centered around the pursuit of entertainment and leisure. These lavishly decorated and frescoed palaces are adorned with handcrafted furniture and works of art and surrounded by gardens that retain their original layout to this day–a very rare feature.

To read more and/or purchase: https://www.rizzoliusa.com/book/9788891821324

Join the Red Bull Air Force for a wingsuit flying adventure as they travel into Switzerland’s Vaud Alps.

Red Bull Air Force members Mike Swanson, Miles Daisher and Andy Farrington start their journey in the town of Bex, Switzerland, eventually making it to the top of the Les Diablerets glacier—a whopping 3,210 meters above sea level.

Watch as the crew, joined by athletes Roberta Mancino and Scotty Bob Morgan wingsuit fly past “Glacier 3000,” a suspension bridge connecting two mountain peaks. With scenic views and jaw-dropping action, it’s the Swiss adventure of a lifetime— presented with the support of Villars-Gryon-Les Diablerets-Bex-Glacier 3000.

Website: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLnuf8iyXggLEp_2gb3jtTm_D4nle3jrnz

Today, Monday December 16, marks 75 years since the beginning of one of World War II’s most savage battles. In December 1944, the Nazi army surprised U.S. and Allied forces in the frozen forests of Belgium. Badly outnumbered, the U.S. lost 10,000 soldiers amid frigid conditions in the war’s deadliest conflict. John Yang reports on the commemoration of what became known as the Battle of the Bulge.

Today, Monday December 16, marks 75 years since the beginning of one of World War II’s most savage battles. In December 1944, the Nazi army surprised U.S. and Allied forces in the frozen forests of Belgium. Badly outnumbered, the U.S. lost 10,000 soldiers amid frigid conditions in the war’s deadliest conflict. John Yang reports on the commemoration of what became known as the Battle of the Bulge.

Filmed, Edited and Directed by: Joerg Daiber

I will never understand why so many people go to such an obvious Insta-tourist-trap like Santorini when there are so many amazing alternatives in Greece. Take Amorgos for instance. It’s the easternmost island in Greece’s Cyclades island group. With a land area of just 121 square kilometers, the island has a population of nearly 2000 people. It’s incredibly beautiful and no mass tourism is spoiling the fun so far.

The island was featured in Luc Besson’s film “The Big Blue.” Enjoy this trip around Amorgos and let me know what you think in the comments below. Shot by Joerg Daiber during the Yperia Film Festival in Amorgos.

Website: http://www.spoonfilm.com/

From a Literary Review online review:

The Toulousain Charles Dantzig wrote, ‘I find the Marseillais tiresome, especially those who, as soon as you speak to them, start to bang on about the uniqueness of being Marseillais, adding with a particular sort of whining machismo that no one likes them and everyone defames them. Their humour is nothing more than pitiable braggadocio.’ Régis Jauffret, who grew up there, is pithier: ‘Marseille is a tragic city. It formed my imagination.’ (It’s an imagination of peerless bleakness.)

The Toulousain Charles Dantzig wrote, ‘I find the Marseillais tiresome, especially those who, as soon as you speak to them, start to bang on about the uniqueness of being Marseillais, adding with a particular sort of whining machismo that no one likes them and everyone defames them. Their humour is nothing more than pitiable braggadocio.’ Régis Jauffret, who grew up there, is pithier: ‘Marseille is a tragic city. It formed my imagination.’ (It’s an imagination of peerless bleakness.)

Nicholas Hewitt died in March, less than a month after completing the text of Wicked City. It’s a fine monument to his curiosity, compendious knowledge, resourcefulness and measured enthusiasm. He calls it ‘a series of snapshots’, which is perhaps too modest. If they are snapshots, they have been photoshopped and retouched to accord with his vision of the city and its well-rehearsed mythology of outsiderdom and exceptionalism, edginess and banditry. And his aspiration to explore Marseille’s hold on the ‘nation’s imagination’ is also too modest. The ‘international imagination’ would be more apt.

Nicholas Hewitt died in March, less than a month after completing the text of Wicked City. It’s a fine monument to his curiosity, compendious knowledge, resourcefulness and measured enthusiasm. He calls it ‘a series of snapshots’, which is perhaps too modest. If they are snapshots, they have been photoshopped and retouched to accord with his vision of the city and its well-rehearsed mythology of outsiderdom and exceptionalism, edginess and banditry. And his aspiration to explore Marseille’s hold on the ‘nation’s imagination’ is also too modest. The ‘international imagination’ would be more apt.

To read more: https://literaryreview.co.uk/babylon-on-sea

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the history and social impact of coffee. From its origins in Ethiopia, coffea arabica spread through the Ottoman Empire before reaching Western Europe where, in the 17th century, coffee houses were becoming established.

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the history and social impact of coffee. From its origins in Ethiopia, coffea arabica spread through the Ottoman Empire before reaching Western Europe where, in the 17th century, coffee houses were becoming established.There, caffeinated customers stayed awake for longer and were more animated, and this helped to spread ideas and influence culture. Coffee became a colonial product, grown by slaves or indentured labour, with coffea robusta replacing arabica where disease had struck, and was traded extensively by the Dutch and French empires; by the 19th century, Brazil had developed into a major coffee producer, meeting demand in the USA that had grown on the waggon trails.

With

Judith Hawley

Professor of 18th Century Literature at Royal Holloway, University of London

Markman Ellis

Professor of 18th Century Studies at Queen Mary University of London

And

Jonathan Morris

Professor in Modern History at the University of Hertfordshire

Producer: Simon Tillotson

Filmed, Edited and Directed by: Txema Ortiz

Navarra a beautiful and wonderful place. A lost paradise.

4K timelapse done entirely in Navarra. This video shows only a small part of the many charming places that this land has, in which you can admire various areas of the Navarra geography, its contrasts and its diversity of landscapes, which make it a very beautiful place to landscape and cultural level, a place to visit because it is worth it, its landscapes, its people, its culture and its cuisine are unique.

Video made with more than 15,000 photographs and several months of work at different times of the year.

Website: https://vimeo.com/txemaortiz