Though U.S. legislation targeting the problem of surprise medical bills advanced out of key congressional committees in 2019 with support from leaders in both parties, Congress ultimately failed to pass a law to end such bills.

Though U.S. legislation targeting the problem of surprise medical bills advanced out of key congressional committees in 2019 with support from leaders in both parties, Congress ultimately failed to pass a law to end such bills.

Erin Fuse Brown is an associate professor of law at Georgia State University. Stephen Morrissey, the interviewer, is the Executive Managing Editor of the Journal.

Center for the Digital Future at USC Annenberg (Feb 19, 2020):

Many Americans are willing to make significant personal tradeoffs to lower their health insurance rates or medical costs, such as agreeing to 24/7 personal monitoring or working with artificial intelligence instead of a human doctor, the Center for the Digital Future at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism finds.

Many Americans are willing to make significant personal tradeoffs to lower their health insurance rates or medical costs, such as agreeing to 24/7 personal monitoring or working with artificial intelligence instead of a human doctor, the Center for the Digital Future at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism finds.

Among the study’s findings:

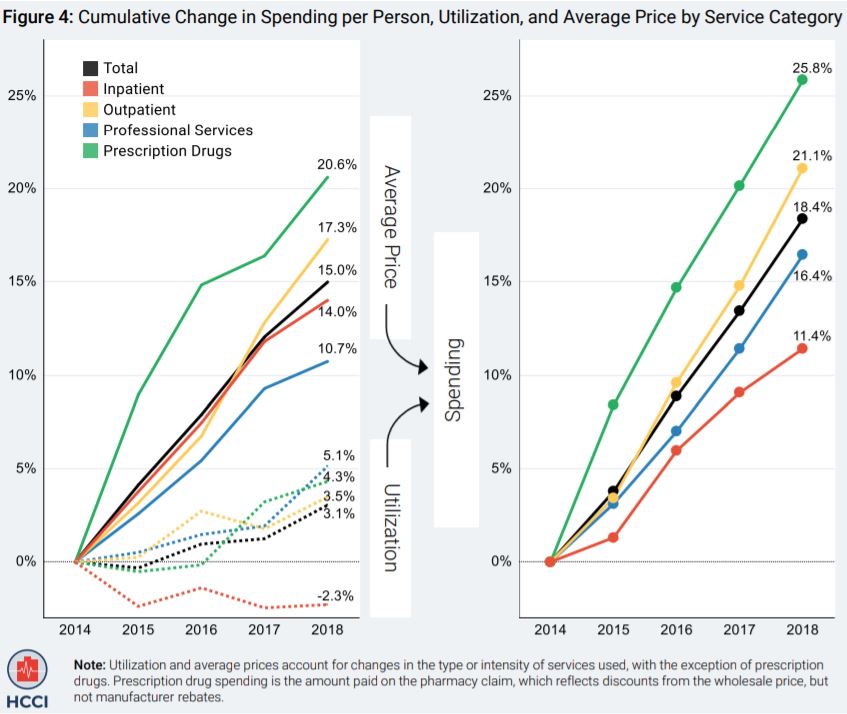

Per-Person Health Care Spending Grew 18% from 2014 to 2018, Driven Mostly by Prices

The report examines four groups of health care services and dozens of sub-categories. Of the four major categories, outpatient visits and procedures saw the highest 2018 spending increase (5.5%). Other notable trends include:

From a JAMA Network online article (February 4, 2020):

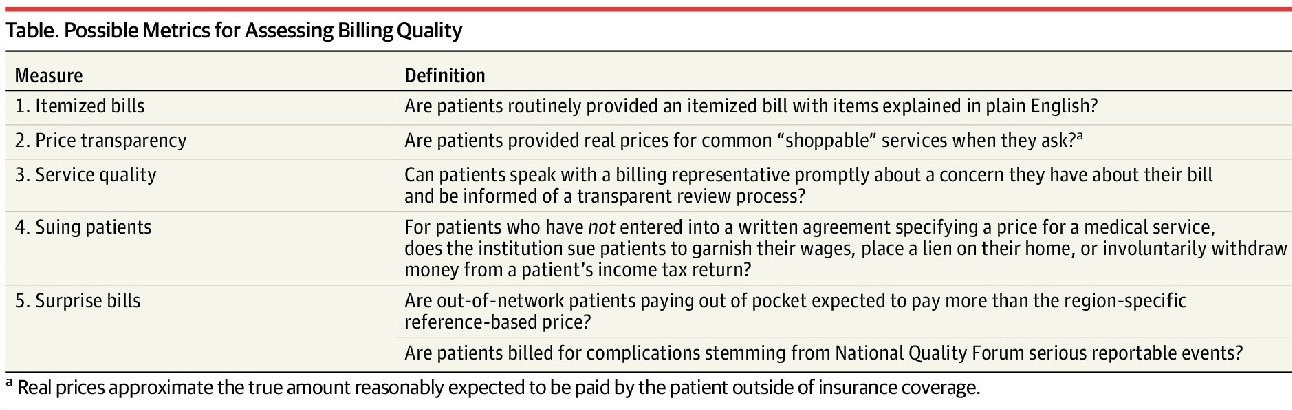

High medical prices and billing practices may reduce public trust in the medical profession and can result in the avoidance of care. In a survey of 1000 patients, 64% reported that they delayed or neglected seeking medical care in the past year because of concern about high medical bills. The field of quality science in health care has developed measures of medical complications; however, there are no standardized metrics of billing quality.

High medical prices and billing practices may reduce public trust in the medical profession and can result in the avoidance of care. In a survey of 1000 patients, 64% reported that they delayed or neglected seeking medical care in the past year because of concern about high medical bills. The field of quality science in health care has developed measures of medical complications; however, there are no standardized metrics of billing quality.

A recent study found that only 53 of 101 hospitals were able to provide a price for standard coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Notably, among the hospitals that provided a price, the price ranged from approximately $44 000 and $448 000 and was not associated with quality of care as measured by risk-adjusted outcomes and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons composite quality score.

A recent study found that only 53 of 101 hospitals were able to provide a price for standard coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Notably, among the hospitals that provided a price, the price ranged from approximately $44 000 and $448 000 and was not associated with quality of care as measured by risk-adjusted outcomes and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons composite quality score.

In the same way that there is wide variation in pricing, aggressive collection tactics also can be highly variable by institution. In a recent analysis, 36% (48/135) of hospitals in Virginia garnished wages of patients with unpaid medical bills, and 5 hospitals accounted for 4690 garnishment cases in 2017, representing 51% of all cases.7 In total, 20 054 lawsuits were filed in Virginia against patients for unpaid debt. For many hospitals that sue patients, legal action follows multiple attempts to contact patients through letters and calls, and some hospitals may offer to set up payment plans or even negotiate charges.

From a Health Care Cost Institute (HCCI) release (12/17/19):

In a WTOP-FM interview, Health Affairs Editor-In-Chief Alan Weil assesses how consumers may (or may not) benefit from two long-anticipated rules, recently unveiled by the Trump Administration, that increase price transparency for both hospitals and insurers.

In a WTOP-FM interview, Health Affairs Editor-In-Chief Alan Weil assesses how consumers may (or may not) benefit from two long-anticipated rules, recently unveiled by the Trump Administration, that increase price transparency for both hospitals and insurers.From a New York Times online article:

For new patients, whose visits entail more work than those of established patients, facility fees typically range from $131 to $322 per visit; for established patients, they are slightly lower. In surgical centers and free-standing emergency rooms, the facility fee can be thousands of dollars.

For new patients, whose visits entail more work than those of established patients, facility fees typically range from $131 to $322 per visit; for established patients, they are slightly lower. In surgical centers and free-standing emergency rooms, the facility fee can be thousands of dollars.

A facility fee is an additional charge that some medical practices can add to the cost of each doctor visit. The additional charge usually comes as a surprise because, unlike an exam or a test or treatment, the facility fee is not tied directly to hands-on care.

The purpose of the facility fee is to compensate hospitals for the expense of maintaining the physical premises. Hospital-owned, off-campus medical practices are also allowed to charge the facility fee to cover specific regulatory requirements, such as building codes, disaster preparedness, equipment redundancy and other items that are largely invisible to patients.

To read more: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/01/well/live/why-was-my-doctor-visit-suddenly-so-expensive.html