The Moulin Rouge, the famous cabaret with a windmill that opened in the Montmartre section of Paris 130 years ago, is still drawing crowds to its spectacular shows featuring a chorus line of often-topless dancers. And it’s now  the inspiration for a hit Broadway musical. Correspondent Alina Cho visits the landmark that has inspired artists and writers (and even marriage proposals), and talks with its artistic director and dancers, along with the Tony Award-winning set designer of the new Broadway show, “Moulin Rouge!: The Musical.”

the inspiration for a hit Broadway musical. Correspondent Alina Cho visits the landmark that has inspired artists and writers (and even marriage proposals), and talks with its artistic director and dancers, along with the Tony Award-winning set designer of the new Broadway show, “Moulin Rouge!: The Musical.”

Moulin Rouge (“Red Mill”) is a cabaret in Paris, France.

The original house, which burned down in 1915, was co-founded in 1889 by Charles Zidler and Joseph Oller, who also owned the Paris Olympia. Close to Montmartre in the Paris district of Pigalle on Boulevard de Clichy in the 18th arrondissement, it is marked by the red windmill on its roof. The closest métro station is Blanche.

Moulin Rouge is best known as the birthplace of the modern form of the can-can dance. Originally introduced as a seductive dance by the courtesans who operated from the site, the can-can dance revue evolved into a form of entertainment of its own and led to the introduction of cabarets across Europe. Today, the Moulin Rouge is a tourist attraction, offering musical dance entertainment for visitors from around the world. The club’s decor still contains much of the romance of fin de siècle France.

From Wikipedia

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, historian, writer, essayist, social critic, political activist, and Nobel laureate. At various points in his life, Russell considered himself a liberal, a socialist and a pacifist, although he also confessed that his sceptical nature had led him to feel that he had “never been any of these things, in any profound sense.” Russell was born in Monmouthshire into one of the most prominent aristocratic families in the United Kingdom.

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, historian, writer, essayist, social critic, political activist, and Nobel laureate. At various points in his life, Russell considered himself a liberal, a socialist and a pacifist, although he also confessed that his sceptical nature had led him to feel that he had “never been any of these things, in any profound sense.” Russell was born in Monmouthshire into one of the most prominent aristocratic families in the United Kingdom.

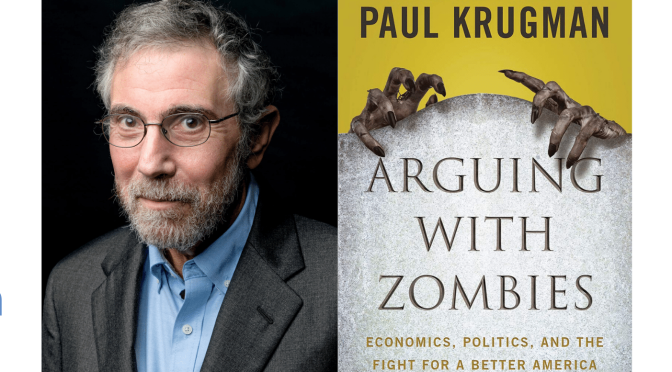

Bloomberg Opinion columnist Barry Ritholtz interviews economist, bestselling author and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman, whose most recent book is “Arguing With Zombies: Economics, Politics, and the Fight for a Better Future.”

Bloomberg Opinion columnist Barry Ritholtz interviews economist, bestselling author and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman, whose most recent book is “Arguing With Zombies: Economics, Politics, and the Fight for a Better Future.”  Paul Robin Krugman (born February 28, 1953) is an American economist who is the Distinguished Professor of Economics at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, and a columnist for The New York Times. In 2008, Krugman was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his contributions to New Trade Theory and New Economic Geography. The Prize Committee cited Krugman’s work explaining the patterns of international trade and the geographic distribution of economic activity, by examining the effects of economies of scale and of consumer preferences for diverse goods and services.

Paul Robin Krugman (born February 28, 1953) is an American economist who is the Distinguished Professor of Economics at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, and a columnist for The New York Times. In 2008, Krugman was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his contributions to New Trade Theory and New Economic Geography. The Prize Committee cited Krugman’s work explaining the patterns of international trade and the geographic distribution of economic activity, by examining the effects of economies of scale and of consumer preferences for diverse goods and services.

The vivid photographs are arranged according to the signs’ imagery, with sections such as Spirit of the West, On the Road, Now That’s Entertainment, and Ladies, Diving Girls & Mermaids. Sixteen of the most iconic landmark signs include brief histories on how that unique sign came to be. A resource section includes a photography index by location and a Neon Museums Visitor’s Guide.

The vivid photographs are arranged according to the signs’ imagery, with sections such as Spirit of the West, On the Road, Now That’s Entertainment, and Ladies, Diving Girls & Mermaids. Sixteen of the most iconic landmark signs include brief histories on how that unique sign came to be. A resource section includes a photography index by location and a Neon Museums Visitor’s Guide.

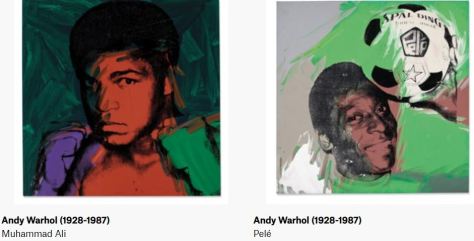

‘The sports stars of today are the movie stars of yesterday,’ proclaimed the artist. It was true; thanks to rapid advances in TV broadcasting, sporting champions in the 1970s were starting to achieve the same level of popularity as other entertainers.

‘The sports stars of today are the movie stars of yesterday,’ proclaimed the artist. It was true; thanks to rapid advances in TV broadcasting, sporting champions in the 1970s were starting to achieve the same level of popularity as other entertainers.