-

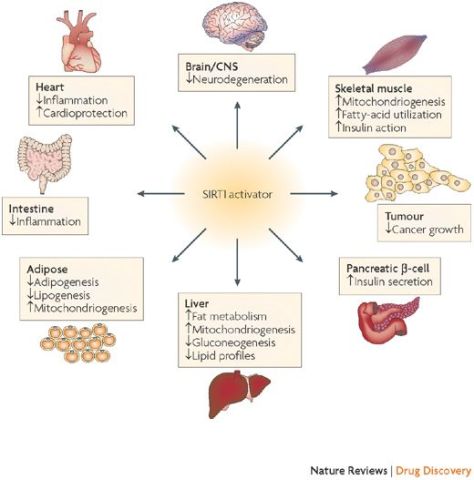

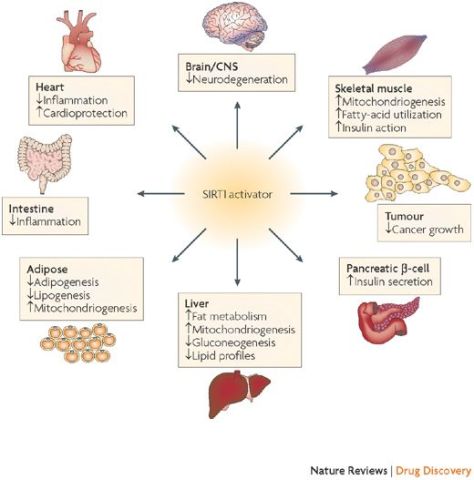

Sirtuins are a family of signaling proteins involved in metabolic regulation. SIRT1 (along with SIRT6 and SIRT7) are proteins are employed in DNA repair.

From Wikipedia:

Sirtuins are a class of proteins that possess either mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase, or deacylase activity, including deacetylase, desuccinylase, demalonylase, demyristoylase and depalmitoylase activity. The name Sir2 comes from the yeast gene ‘silent mating-type information regulation 2‘, the gene responsible for cellular regulation in yeast.

From in vitro studies, sirtuins are implicated in influencing cellular processes like aging, transcription, apoptosis, inflammation and stress resistance, as well as energy efficiency and alertness during low-calorie situations. As of 2018, there was no clinical evidence that sirtuins affect human aging.

Aging

Although preliminary studies with resveratrol, an activator of deacetylases such as SIRT1, led some scientists to speculate that resveratrol may extend lifespan, there was no clinical evidence for such an effect, as of 2018.

In vitro studies shown that calorie restriction regulates the plasma membrane redox system, involved in mitochondrial homeostasis, and the reduction of inflammation through cross-talks between SIRT1 and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), but the role of sirtuins in longevity is still unclear, as calorie restriction in yeast could extend lifespan in the absence of Sir2 or other sirtuins, while the in vivo activation of Sir2 by calorie restriction or resveratrol to extend lifespan has been challenged in multiple organisms.

In this episode of the podcast, Nature reporter Davide Castelvecchi joins us to talk about the big science events to look out for in 2020. We’ll hear about multiple missions to Mars, a prototype electric car, efforts to prevent dengue, and more.

In this episode of the podcast, Nature reporter Davide Castelvecchi joins us to talk about the big science events to look out for in 2020. We’ll hear about multiple missions to Mars, a prototype electric car, efforts to prevent dengue, and more.

In this video, best-selling author Abraham Verghese, MD, discusses the origins of the study he coauthored identifying 5 practices that foster meaningful connections between physicians and patients.

In this video, best-selling author Abraham Verghese, MD, discusses the origins of the study he coauthored identifying 5 practices that foster meaningful connections between physicians and patients.

The proportion of patients who have two or more medical conditions simultaneously is, however, rising steadily. This is currently termed multimorbidity, although patient groups prefer the more intuitive “multiple health conditions.” In high income countries, multimorbidity is mainly driven by age, and the proportion of the population living with two or more diseases is steadily increasing because of demographic change. This trend will continue.

The proportion of patients who have two or more medical conditions simultaneously is, however, rising steadily. This is currently termed multimorbidity, although patient groups prefer the more intuitive “multiple health conditions.” In high income countries, multimorbidity is mainly driven by age, and the proportion of the population living with two or more diseases is steadily increasing because of demographic change. This trend will continue.

Among older adults age 50–80, 43% had ever reviewed doctor ratings; 14% had reviewed ratings more than once in the past year, 19% had done so once in the past year, and 10% had reviewed ratings more than one year ago.

Among older adults age 50–80, 43% had ever reviewed doctor ratings; 14% had reviewed ratings more than once in the past year, 19% had done so once in the past year, and 10% had reviewed ratings more than one year ago. Ratings and reviews for nearly everything can be found online these days, including doctors. How are older adults using these ratings in their decisions about choosing doctors? In May 2019, the University of Michigan National Poll on Healthy Aging asked a

Ratings and reviews for nearly everything can be found online these days, including doctors. How are older adults using these ratings in their decisions about choosing doctors? In May 2019, the University of Michigan National Poll on Healthy Aging asked a

WHO’s definition of health is famously “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”. One of the oldest medical texts we know of, The Science of Medicine attributed to Hippocrates, sets out the goal of medicine in comparable terms: “the complete removal of the distress of the sick”.

WHO’s definition of health is famously “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”. One of the oldest medical texts we know of, The Science of Medicine attributed to Hippocrates, sets out the goal of medicine in comparable terms: “the complete removal of the distress of the sick”.