Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, historian, writer, essayist, social critic, political activist, and Nobel laureate. At various points in his life, Russell considered himself a liberal, a socialist and a pacifist, although he also confessed that his sceptical nature had led him to feel that he had “never been any of these things, in any profound sense.” Russell was born in Monmouthshire into one of the most prominent aristocratic families in the United Kingdom.

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, historian, writer, essayist, social critic, political activist, and Nobel laureate. At various points in his life, Russell considered himself a liberal, a socialist and a pacifist, although he also confessed that his sceptical nature had led him to feel that he had “never been any of these things, in any profound sense.” Russell was born in Monmouthshire into one of the most prominent aristocratic families in the United Kingdom.

In the early 20th century, Russell led the British “revolt against idealism”. He is considered one of the founders of analytic philosophy along with his predecessor Gottlob Frege, colleague G. E. Moore and protégé Ludwig Wittgenstein. He is widely held to be one of the 20th century’s premier logicians. With A. N. Whitehead he wrote Principia Mathematica, an attempt to create a logical basis for mathematics, the quintessential work of classical logic. His philosophical essay “On Denoting” has been considered a “paradigm of philosophy”. His work has had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, artificial intelligence, cognitive science, computer science (see type theory and type system) and philosophy, especially the philosophy of language, epistemology and metaphysics.

Russell was a prominent anti-war activist and he championed anti-imperialism. Occasionally, he advocated preventive nuclear war, before the opportunity provided by the atomic monopoly had passed and he decided he would “welcome with enthusiasm” world government. He went to prison for his pacifism during World War I.[75] Later, Russell concluded that war against Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany was a necessary “lesser of two evils” and criticised Stalinist totalitarianism, attacked the involvement of the United States in the Vietnam War and was an outspoken proponent of nuclear disarmament. In 1950, Russell was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature “in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought”.

From Wikipedia

As you will see from my portfolio, travel plays a huge part in my image-making. I visited nine countries in 2017 alone, and close to twenty since my journey into architectural photography began. I have always been fascinated by different cultures, foods, textures and colours. It is this love for travel, combined with my deep passion for photography, that keeps me motivated and dedicated to putting in the long lonely hours of research and logistical planning to then get out with the camera time and time again.

As you will see from my portfolio, travel plays a huge part in my image-making. I visited nine countries in 2017 alone, and close to twenty since my journey into architectural photography began. I have always been fascinated by different cultures, foods, textures and colours. It is this love for travel, combined with my deep passion for photography, that keeps me motivated and dedicated to putting in the long lonely hours of research and logistical planning to then get out with the camera time and time again.

comes over my life when I think […] that I’ve earned my reputation out of other people’s downfall. I’ve photographed dead people and I’ve photographed dying people, and people looking at me who are about to be murdered in alleyways. So I carry the guilt of survival, the shame of not being able to help dying people.’

comes over my life when I think […] that I’ve earned my reputation out of other people’s downfall. I’ve photographed dead people and I’ve photographed dying people, and people looking at me who are about to be murdered in alleyways. So I carry the guilt of survival, the shame of not being able to help dying people.’  On top of a hill a few miles from Don McCullin’s house in Somerset is a dew pond, a perfectly circular artificial pond for watering livestock. Nobody knows how long it has been there; some dew ponds date back to prehistoric times, and it’s tempting to think that this one served the Bronze Age hill-fort that overlooks the site. McCullin is obsessed with the pond. For more than 30 years, whenever he has had the time, he has walked up the hill and stood there with his camera waiting for the right moment to take a photograph. Often, the moment never comes: he can spend hours there, just looking. ‘It’s as if it has a hold over me,’ he tells me when I visit him at home in early January. ‘I can’t leave it alone, I photograph it all the time. And yet I think I’ve done my best picture the first time I ever did it. I can’t tell you how.’

On top of a hill a few miles from Don McCullin’s house in Somerset is a dew pond, a perfectly circular artificial pond for watering livestock. Nobody knows how long it has been there; some dew ponds date back to prehistoric times, and it’s tempting to think that this one served the Bronze Age hill-fort that overlooks the site. McCullin is obsessed with the pond. For more than 30 years, whenever he has had the time, he has walked up the hill and stood there with his camera waiting for the right moment to take a photograph. Often, the moment never comes: he can spend hours there, just looking. ‘It’s as if it has a hold over me,’ he tells me when I visit him at home in early January. ‘I can’t leave it alone, I photograph it all the time. And yet I think I’ve done my best picture the first time I ever did it. I can’t tell you how.’

The plan was simple: he would embark on a journey through his life in food in pursuit of the meal to end all meals. It’s a quest that takes him from necking oysters on the Louisiana shoreline to forking away the finest French pastries in Tokyo, and from his earliest memories of snails in garlic butter, through multiple pig-based banquets, to the unforgettable final meal itself.

The plan was simple: he would embark on a journey through his life in food in pursuit of the meal to end all meals. It’s a quest that takes him from necking oysters on the Louisiana shoreline to forking away the finest French pastries in Tokyo, and from his earliest memories of snails in garlic butter, through multiple pig-based banquets, to the unforgettable final meal itself.

“Life begins at 55, the age at which I published my first book,” he wrote in “From Eros to Gaia,” one of the collections of his writings that appeared while he was a professor of physics at the Institute for Advanced Study — an august position for someone who finished school without a Ph.D. The lack of a doctorate was a badge of honor, he said. With his slew of honorary degrees and a fellowship in the Royal Society, people called him Dr. Dyson anyway.

“Life begins at 55, the age at which I published my first book,” he wrote in “From Eros to Gaia,” one of the collections of his writings that appeared while he was a professor of physics at the Institute for Advanced Study — an august position for someone who finished school without a Ph.D. The lack of a doctorate was a badge of honor, he said. With his slew of honorary degrees and a fellowship in the Royal Society, people called him Dr. Dyson anyway.

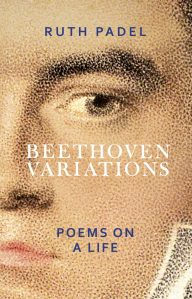

Like Beethoven, the poet Ruth Padel first came to love and understand music through playing the viola. Her great grandfather, a concert pianist, studied music in Leipzig with Beethoven’s friend and contemporary. Her latest collection

Like Beethoven, the poet Ruth Padel first came to love and understand music through playing the viola. Her great grandfather, a concert pianist, studied music in Leipzig with Beethoven’s friend and contemporary. Her latest collection  She was joined in an evening of readings and conversation about Beethoven, poetry and music by poets Raymond Antrobus and Anthony Anaxagorou, both of whom are currently engaged in creative projects working on and from the life and work of Beethoven.

She was joined in an evening of readings and conversation about Beethoven, poetry and music by poets Raymond Antrobus and Anthony Anaxagorou, both of whom are currently engaged in creative projects working on and from the life and work of Beethoven. Ruth Sophia Padel (born 8 May 1946) is a British poet, novelist and non-fiction author, in whose work “the journey is the stepping stone to lyrical reflections on the human condition”. She is known for her explorations through poetry of migration and refugees,science, and homelessness; for her involvement in wildlife conservation, Greece, and music; and for her belief that poetry “connects with every area of life” and “has a responsibility to look at the world”. She is Trustee for conservation charity New Networks for Nature, has served on the Board of the Zoological Society of London, and broadcasts for BBC Radio 3 and 4 on poetry, wildlife and music. In 2013 she joined King’s College London, where she is Professor of Poetry.

Ruth Sophia Padel (born 8 May 1946) is a British poet, novelist and non-fiction author, in whose work “the journey is the stepping stone to lyrical reflections on the human condition”. She is known for her explorations through poetry of migration and refugees,science, and homelessness; for her involvement in wildlife conservation, Greece, and music; and for her belief that poetry “connects with every area of life” and “has a responsibility to look at the world”. She is Trustee for conservation charity New Networks for Nature, has served on the Board of the Zoological Society of London, and broadcasts for BBC Radio 3 and 4 on poetry, wildlife and music. In 2013 she joined King’s College London, where she is Professor of Poetry.

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, historian, writer, essayist, social critic, political activist, and Nobel laureate. At various points in his life, Russell considered himself a liberal, a socialist and a pacifist, although he also confessed that his sceptical nature had led him to feel that he had “never been any of these things, in any profound sense.” Russell was born in Monmouthshire into one of the most prominent aristocratic families in the United Kingdom.

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, historian, writer, essayist, social critic, political activist, and Nobel laureate. At various points in his life, Russell considered himself a liberal, a socialist and a pacifist, although he also confessed that his sceptical nature had led him to feel that he had “never been any of these things, in any profound sense.” Russell was born in Monmouthshire into one of the most prominent aristocratic families in the United Kingdom.