From a New Atlas online review:

Now VanDoIt has capitalized on the launch of the 2020 Transit AWD to make its modular vans even more capable and versatile, letting owners option right up to a full-blown off-road, off-grid adventure vessel. It received a pre-production prototype from Ford and got to work rejiggering its modular conversion around the updated van, bearing fruit in the all-new LIV.

Earlier this year, Ford announced plans to launch an all-wheel-drive Transit as part of its updated 2020 US van lineup. That might seem like small product news, but it means that the US market will finally get a second factory AWD van to compete with the Mercedes Sprinter 4×4 that came over the Atlantic in 2015. It also means we can expect to see camper vans that look more like this one. The masters of modularity at VanDoIt become the first Americans to offer a camper van on the all-new Transit AWD, adding the LIV van as the second model in their lineup of super-flexible adventure vans. With a full selection of plug-and-play equipment, the LIV can flex between eight-seat, toy-hauling sleeper van and fully equipped multi-bed camper.

I chose to call myself a portrait photographer because labels were always being thrown on me. When I was at Rolling Stone I was a ‘rock-and-roll photographer’, at Vanity Fair I was a ‘celebrity photographer’. You know, I’m just a photographer. I realised I wasn’t really a journalist. I have a point of view and, while these photographs that I call portraits can be conceptual or illustrative, that keeps me on the straight and narrow. So I settled on this brand called ‘portraits’ because it had a lot of leeway. But I don’t think of myself that way now: I think of myself as a conceptual artist using photography.

I chose to call myself a portrait photographer because labels were always being thrown on me. When I was at Rolling Stone I was a ‘rock-and-roll photographer’, at Vanity Fair I was a ‘celebrity photographer’. You know, I’m just a photographer. I realised I wasn’t really a journalist. I have a point of view and, while these photographs that I call portraits can be conceptual or illustrative, that keeps me on the straight and narrow. So I settled on this brand called ‘portraits’ because it had a lot of leeway. But I don’t think of myself that way now: I think of myself as a conceptual artist using photography. I remember going to the Factory in 1976 and watching Andy Warhol work. I’d been there before, earlier in the 70s, photographing Joe Dallesandro and Holly Woodlawn, and then Paul Morrissey. Warhol was a fixture of New York. It was just shocking when he died, because he was everywhere. I don’t know how he did it, but he was out at everything. You felt that if he was at a place you were at, then you were at the right place.

I remember going to the Factory in 1976 and watching Andy Warhol work. I’d been there before, earlier in the 70s, photographing Joe Dallesandro and Holly Woodlawn, and then Paul Morrissey. Warhol was a fixture of New York. It was just shocking when he died, because he was everywhere. I don’t know how he did it, but he was out at everything. You felt that if he was at a place you were at, then you were at the right place.

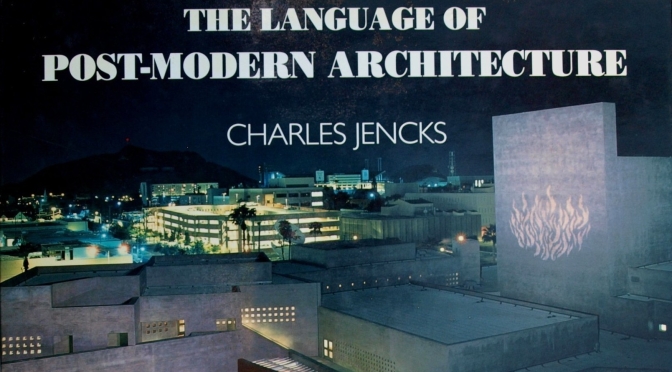

Jencks’s book grew out of his PhD thesis, supervised by Reyner Banham at the University of London in the late 1960s, and paved the way for his later, more explicitly polemical The Language of Post-Modern Architecture (1977). In this bestselling book, Jencks set out his stall for a pluralist architecture that rejected what he saw as modernism’s reductive ‘univalent’ approach, swapping it for a symbolically rich and historically engaged ‘multivalent’ postmodernism. For good or bad it became the defining book of its era, an unabashed rejection of mainstream modernism that ushered in a new architectural style.

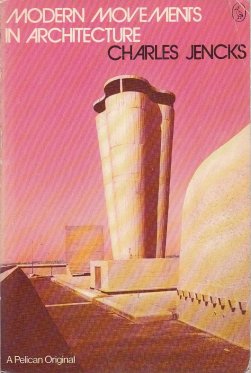

Jencks’s book grew out of his PhD thesis, supervised by Reyner Banham at the University of London in the late 1960s, and paved the way for his later, more explicitly polemical The Language of Post-Modern Architecture (1977). In this bestselling book, Jencks set out his stall for a pluralist architecture that rejected what he saw as modernism’s reductive ‘univalent’ approach, swapping it for a symbolically rich and historically engaged ‘multivalent’ postmodernism. For good or bad it became the defining book of its era, an unabashed rejection of mainstream modernism that ushered in a new architectural style. Modern Movements in Architecture (1973) by Charles Jencks was one of the first books on architecture I read, a birthday present given to me the summer before I started my degree. In some ways, it spoiled things: I thought all architecture books would be that much fun. Modern Movements in Architecture is a complex and sophisticated history, but it wears its learning lightly. It relates architecture to a wider cultural discourse and it is unafraid to be critical, even of some architects, such as Mies van der Rohe, who were previously considered to be above criticism.

Modern Movements in Architecture (1973) by Charles Jencks was one of the first books on architecture I read, a birthday present given to me the summer before I started my degree. In some ways, it spoiled things: I thought all architecture books would be that much fun. Modern Movements in Architecture is a complex and sophisticated history, but it wears its learning lightly. It relates architecture to a wider cultural discourse and it is unafraid to be critical, even of some architects, such as Mies van der Rohe, who were previously considered to be above criticism.

“Everywhere is the wait and the gathering,” concludes “Resort.” A kind of soporific haze has seeped into de Chirico’s imagination, asserted through evocations of sleeping and dreaming. Even the violence and ambiguous sexual imagery of “The Mysterious Night” yield to a final note of definitive somnolence: “Everything sleeps; even the owls and the bats who also in the dream dream of sleeping.”

“Everywhere is the wait and the gathering,” concludes “Resort.” A kind of soporific haze has seeped into de Chirico’s imagination, asserted through evocations of sleeping and dreaming. Even the violence and ambiguous sexual imagery of “The Mysterious Night” yield to a final note of definitive somnolence: “Everything sleeps; even the owls and the bats who also in the dream dream of sleeping.” He daydreams of Mexico or Alaska and invokes a future-oriented “avant-city” and a distant day where he is immortalized, albeit in an old-fashioned mode as a “man of marble.”

He daydreams of Mexico or Alaska and invokes a future-oriented “avant-city” and a distant day where he is immortalized, albeit in an old-fashioned mode as a “man of marble.”

Every possible step is done online, and for most meals customers must reserve—and often pay—in advance, essentially buying tickets through a service called Tock that’s mostly used only by high-end restaurants. This means no host manning a podium, no reservation or PR teams, no extra staff on a slow night, almost no food waste, and better guest communications. It also allowed them to go from 20 employees to four full-time and three part-time workers.

Every possible step is done online, and for most meals customers must reserve—and often pay—in advance, essentially buying tickets through a service called Tock that’s mostly used only by high-end restaurants. This means no host manning a podium, no reservation or PR teams, no extra staff on a slow night, almost no food waste, and better guest communications. It also allowed them to go from 20 employees to four full-time and three part-time workers.

One of the most impressive aspects of the book is the wealth of contextual material, which never feels digressional but illuminatingly sets the scene for Hilliard’s remarkable life and achievement. His early life in Exeter; the family networks of goldsmiths in Devon and London; the political, religious and cultural worlds he would have encountered in London, Geneva, Paris and also – usually overlooked – in Wesel and Frankfurt; all make for compelling reading. This book is not just the definitive biography of Hilliard but essential reading for anyone interested in late 16th- and early 17th-century England.

One of the most impressive aspects of the book is the wealth of contextual material, which never feels digressional but illuminatingly sets the scene for Hilliard’s remarkable life and achievement. His early life in Exeter; the family networks of goldsmiths in Devon and London; the political, religious and cultural worlds he would have encountered in London, Geneva, Paris and also – usually overlooked – in Wesel and Frankfurt; all make for compelling reading. This book is not just the definitive biography of Hilliard but essential reading for anyone interested in late 16th- and early 17th-century England.

In this artist’s book of 120 iPhone and iPad drawings,

In this artist’s book of 120 iPhone and iPad drawings,

The VillageMD primary care clinic, called Village Medical at Walgreens, is the first of five sites to open in Houston. Four more clinics are slated to open by the end of the year. The Village Medical clinics are

The VillageMD primary care clinic, called Village Medical at Walgreens, is the first of five sites to open in Houston. Four more clinics are slated to open by the end of the year. The Village Medical clinics are