From a BMJ Study article (April, 2020):

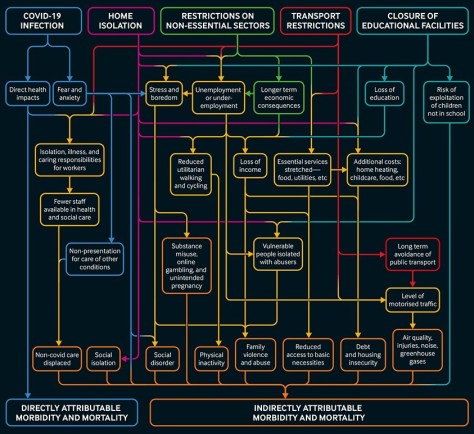

Compared with usual diet, moderate certainty evidence supports modest weight loss and substantial reductions in systolic and diastolic blood pressure for low carbohydrate (eg, Atkins, Zone), low fat (eg, Ornish), and moderate macronutrient (eg, DASH, Mediterranean) diets at six but not 12 months. Differences between diets are, however, generally trivial to small, implying that people can choose the diet they prefer from among many of the available diets (fig 6) without concern about the magnitude of benefits.

The worldwide prevalence of obesity nearly tripled between 1975 and 2018.1 In response, authorities have made dietary recommendations for weight management and cardiovascular risk reduction.23 Diet programmes—some focusing on carbohydrate reduction and others on fat reduction—have been promoted widely by the media and have generated intense debates about their relative merit. Millions of people are trying to lose weight by changing their diet. Thus establishing the effect of dietary macronutrient patterns (carbohydrate reduction v fat reduction v moderate macronutrients) and popular named dietary programmes is important.

Biological and physiological mechanisms have been proposed to explain why some dietary macronutrient patterns and popular dietary programmes should be better than others. A previous network meta-analysis, however, suggested that differences in weight loss between dietary patterns and individual popular named dietary programmes are small and unlikely to be important.4 No systematic review and network meta-analysis has examined the comparative effectiveness of popular dietary programmes for reducing risk factors for cardiovascular disease, an area of continuing controversy.

From a BMJ online release (March 17, 2020):

“The finding in two randomised trials that advice to use ibuprofen results in more severe illness or complications helps confirm that the association seen in observational studies is indeed likely to be causal. Advice to use paracetamol (acetaminophen) is also less likely to result in complications.”

“The finding in two randomised trials that advice to use ibuprofen results in more severe illness or complications helps confirm that the association seen in observational studies is indeed likely to be causal. Advice to use paracetamol (acetaminophen) is also less likely to result in complications.”

Scientists and senior doctors have backed claims by France’s health minister that people showing symptoms of covid-19 should use paracetamol (acetaminophen) rather than ibuprofen, a drug they said might exacerbate the condition.

Ian Jones, a professor of virology at the University of Reading, said that ibuprofen’s anti-inflammatory properties could “dampen down” the immune system, which could slow the recovery process. He added that it was likely, based on similarities between the new virus (SARS-CoV-2) and SARS I, that covid-19 reduces a key enzyme that part regulates the water and salt concentration in the blood and could contribute to the pneumonia seen in extreme cases. “Ibuprofen aggravates this, while paracetamol does not,” he said.

Ian Jones, a professor of virology at the University of Reading, said that ibuprofen’s anti-inflammatory properties could “dampen down” the immune system, which could slow the recovery process. He added that it was likely, based on similarities between the new virus (SARS-CoV-2) and SARS I, that covid-19 reduces a key enzyme that part regulates the water and salt concentration in the blood and could contribute to the pneumonia seen in extreme cases. “Ibuprofen aggravates this, while paracetamol does not,” he said.

From a BMJ Research study (March 4, 2020):

Habitual fish oil supplementation is associated with a 13% lower risk of all cause mortality, a 16% lower risk of CVD mortality, and a 7% lower risk of CVD events among the general population

Habitual fish oil supplementation is associated with a 13% lower risk of all cause mortality, a 16% lower risk of CVD mortality, and a 7% lower risk of CVD events among the general population

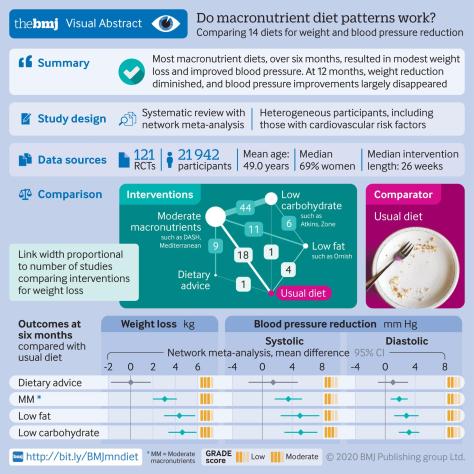

Fish oil is a rich source of long chain omega 3 fatty acids, a group of polyunsaturated fats that primarily include eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid. Initially, these compounds were recommended for daily omega 3 fatty acid supplementation for the prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Consequently, the use of fish oil supplements is widespread in the United Kingdom and other developed countries.

Several mechanisms could explain the benefits for clinical outcome derived from fish oil supplementation. Firstly, the results of several studies have indicated that supplementation with omega 3 fatty acids has beneficial effects on blood pressure, plasma triglycerides, and heart rate, all of which would exert a protective effect against the development of CVD. Secondly, several trials have shown that omega 3 fatty acids can improve flow mediated arterial dilatation, which is a measure of endothelial function and health. Thirdly, omega 3 fatty acids have been shown to possess antiarrhythmic properties that could be clinically beneficial. Finally, studies have reported that fish oil can reduce thrombosis. Additionally, studies have reported that the anti-inflammatory properties of fish oil could have a preventive role in the pathophysiology of CVD outcomes. Other mechanisms could also be involved to explain the effect of fish oil on CVD outcomes.

From a BMJ Research online study (March 4, 2020):

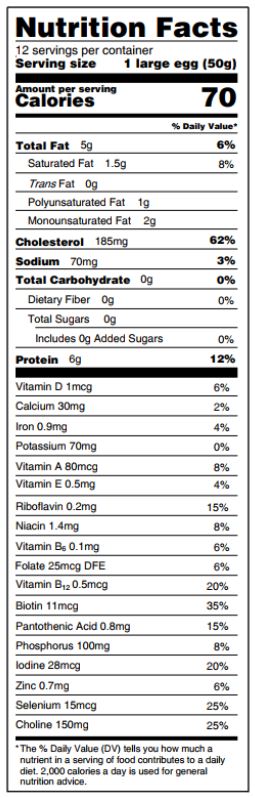

We found no association between egg consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease in three large US cohorts. Results from the updated meta-analysis lend further support to the overall lack of an association between moderate egg consumption (up to one egg per day) and cardiovascular disease risk.

We found no association between egg consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease in three large US cohorts. Results from the updated meta-analysis lend further support to the overall lack of an association between moderate egg consumption (up to one egg per day) and cardiovascular disease risk.

Eggs are a major source of dietary cholesterol, but they are also an affordable source of high quality protein, iron, unsaturated fatty acids, phospholipids, and carotenoids.

Eggs are a major source of dietary cholesterol, but they are also an affordable source of high quality protein, iron, unsaturated fatty acids, phospholipids, and carotenoids.

Introduction: In the United States, cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in men and women. Diet and lifestyle undisputedly play a major part in the development of cardiovascular disease. In the past, limiting dietary cholesterol intake to 300 mg per day was widely recommended to prevent cardiovascular disease. However, because of the weak association between dietary cholesterol and blood cholesterol, and considering that dietary cholesterol is no longer a nutrient of concern for overconsumption, the most recent 2015 dietary guidelines for Americans did not carry forward this recommendation.

From a BMJ Opinion article (Feb 28, 2020):

A lack of adequate knowledge is probably the driving force for the public panic, particularly at the early stages of an outbreak—highlighting the fact that information is crucial. Misunderstandings about the information that is available, even worse exaggerating such information, may further aggravate the panic. Unfortunately, these phenomena are not uncommon. To relieve the public panic, an effective approach would be timely publication of trustworthy research evidence in a manner appropriate for the public.

A lack of adequate knowledge is probably the driving force for the public panic, particularly at the early stages of an outbreak—highlighting the fact that information is crucial. Misunderstandings about the information that is available, even worse exaggerating such information, may further aggravate the panic. Unfortunately, these phenomena are not uncommon. To relieve the public panic, an effective approach would be timely publication of trustworthy research evidence in a manner appropriate for the public.

Click here for real-time update

To date, there have been a number of reports and research papers published in peer reviewed journals. However, this information is largely aimed at researchers and healthcare professionals. The study findings are often obscure for the general public. Some of the published evidence is reporting on early findings and there are some methodological limitations. If inappropriately interpreted, they could misinform the public and could potentially cause further panic or psychological stress. We believe that providing the public with timely and credible evidence and appropriate interpretation is very important. Disseminating the evidence effectively is critical to improving the public’s understanding of the outbreak.

The emergent corona virus (SARS-CoV-2) outbreak in China is fast changing, just this week reported cases of the disease covid-19 jumped as new data became available. In this video Wendy Burns, and Peter Openshaw from Imperial College London explain what we know about the basic structure of the virus, it’s mode of transmission, the symptoms and pathogenesis of the diease, what we currently know about treatment, and how the virus may adapt in the future.

To read more about corona virus, all The BMJ’s resources are being made freely available at https://www.bmj.com/coronavirus

From a The BMJ Views and Reviews article by David Oliver (February 5, 2020):

Last year the Lancet published a paper on the impact of wearing gowns, surveying 928 adult patients and carrying out structured interviews with 10 patients. Over half (58%) reported wearing the gown despite feeling uncertain that it was a medical necessity. Gown design was considered inadequate, with 61% reporting that they struggled to put it on or required assistance and 67% reporting that it didn’t fit. Most worryingly, 72% felt exposed, 60% felt self-conscious, and 57% felt uncomfortable wearing the gown.

Last year the Lancet published a paper on the impact of wearing gowns, surveying 928 adult patients and carrying out structured interviews with 10 patients. Over half (58%) reported wearing the gown despite feeling uncertain that it was a medical necessity. Gown design was considered inadequate, with 61% reporting that they struggled to put it on or required assistance and 67% reporting that it didn’t fit. Most worryingly, 72% felt exposed, 60% felt self-conscious, and 57% felt uncomfortable wearing the gown.

I’ve often wondered why on earth we routinely put so many patients into hospital gowns within minutes of their arrival at hospital.

Sometimes referred to as “dignity gowns,” such dignity as they afford is only in comparison to being stark naked. They don’t come in a wide range of sizes or lengths, and they’re open along the back. You tend to get what you’re given and make do. The effect is to leave patients with lots of exposed flesh, with underwear or buttocks intermittently displayed and a feeling of extreme vulnerability, not to mention being cold if they have no other layers to wear.

From a The BMJ online editorial:

The proportion of patients who have two or more medical conditions simultaneously is, however, rising steadily. This is currently termed multimorbidity, although patient groups prefer the more intuitive “multiple health conditions.” In high income countries, multimorbidity is mainly driven by age, and the proportion of the population living with two or more diseases is steadily increasing because of demographic change. This trend will continue.

The proportion of patients who have two or more medical conditions simultaneously is, however, rising steadily. This is currently termed multimorbidity, although patient groups prefer the more intuitive “multiple health conditions.” In high income countries, multimorbidity is mainly driven by age, and the proportion of the population living with two or more diseases is steadily increasing because of demographic change. This trend will continue.

The cluster around diabetes is a good example, with the common serious disease affecting the heart, nervous system, skin, peripheral vasculature, and eyes. Diabetologists already provide care for the cluster of multiorgan diseases around diabetes, and some specialties, such as geriatrics or general practice, have multimorbidity at their heart. For most, however, training and service organisation are not optimised to face a multimorbidity dominated future.

The shift includes moving from thinking about multimorbidity as a random assortment of individual conditions to recognising it as a series of largely predictable clusters of disease in the same person. Some of these clusters will occur by chance alone because individuals are affected by a variety of commonly occurring diseases. Many, however, will be non-random because of common genetic, behavioural, or environmental pathways to disease. Identifying these clusters is a priority and will help us to be more systematic in our approach to multimorbidity.