What Is Herd Immunity?

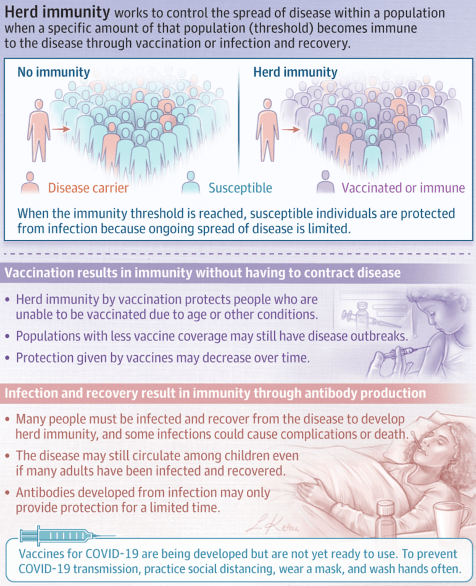

Herd immunity occurs when a significant portion of a population becomes immune to an infectious disease, limiting further disease spread.

Disease spread occurs when some proportion of a population is susceptible to the disease. Herd immunity occurs when a significant portion of a population becomes immune to an infectious disease and the risk of spread from person to person decreases; those who are not immune are indirectly protected because ongoing disease spread is very small.

The proportion of a population who must be immune to achieve herd immunity varies by disease. For example, a disease that is very contagious, such as measles, requires more than 95% of the population to be immune to stop sustained disease transmission and achieve herd immunity.

How Is Herd Immunity Achieved?

Herd immunity may be achieved either through infection and recovery or by vaccination. Vaccination creates immunity without having to contract a disease. Herd immunity also protects those who are unable to be vaccinated, such as newborns and immunocompromised people, because the disease spread within the population is very limited. Communities with lower vaccine coverage may have outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases because the proportion of people who are vaccinated is below the necessary herd immunity threshold. In addition, the protection offered by vaccines may wane over time, requiring repeat vaccination.

Achieving herd immunity through infection relies on enough people being infected with the disease and recovering from it, during which they develop antibodies against future infection. In some situations, even if a large proportion of adults have developed immunity after prior infection, the disease may still circulate among children. In addition, antibodies from a prior infection may only provide protection for a limited duration.

People who do not have immunity to a disease may still contract an infectious disease and have severe consequences of that disease even when herd immunity is very high. Herd immunity reduces the risk of getting a disease but does not prevent it for nonimmune people.

Herd Immunity and COVID-19

There is no effective vaccine against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) yet, although several are currently in development. It is not yet known if having this disease confers immunity to future infection, and if so, for how long. A large proportion of people would likely need to be infected and recover to achieve herd immunity; however, this situation could overwhelm the health care system and lead to many deaths and complications. To prevent disease transmission, keep distance between yourself and others, wash your hands often with soap and water or sanitizer that contains at least 60% alcohol, and wear a face covering in public spaces where it is difficult to avoid close contact with others.

Coffee and tea have been consumed for hundreds of years and have become an important part of cultural traditions and social life.

Coffee and tea have been consumed for hundreds of years and have become an important part of cultural traditions and social life.

We tested the hypothesis that apathy, but not depression, is associated with dementia in patients with SVD. We found that higher baseline apathy, as well as increasing apathy over time, were associated with an increased dementia risk. In contrast, neither baseline depression or change in depression was associated with dementia. The relationship between apathy and dementia remained after controlling for other well-established risk factors including age, education and cognition. Finally, adding apathy to models predicting dementia improved model fit. These results suggest that apathy may be a prodromal symptom of dementia in patients with SVD.

We tested the hypothesis that apathy, but not depression, is associated with dementia in patients with SVD. We found that higher baseline apathy, as well as increasing apathy over time, were associated with an increased dementia risk. In contrast, neither baseline depression or change in depression was associated with dementia. The relationship between apathy and dementia remained after controlling for other well-established risk factors including age, education and cognition. Finally, adding apathy to models predicting dementia improved model fit. These results suggest that apathy may be a prodromal symptom of dementia in patients with SVD.

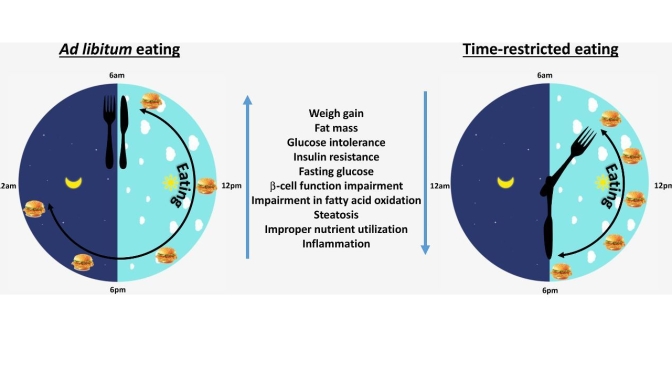

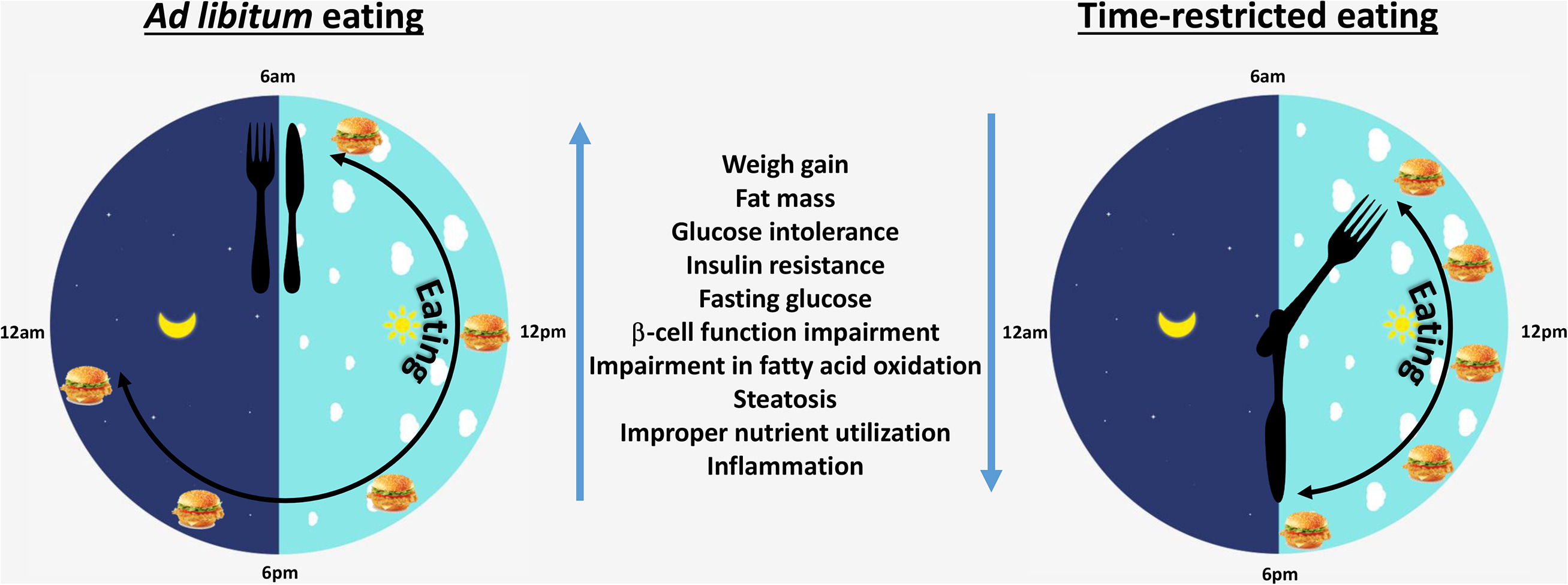

…the beneficial effects of TRE are dose dependent, with greater reductions in body weight, fat mass, and improvement in glucose tolerance when a 9-h protocol was implemented versus 12 and 15 h. The optimal TRE time frame to recommend for people has not been tested. Clear improvements have been noted after 6-, 8-, 9-, and 10-h protocols. It is likely that the greater time restriction would result in greater weight losses, which may maximize the metabolic benefits.

…the beneficial effects of TRE are dose dependent, with greater reductions in body weight, fat mass, and improvement in glucose tolerance when a 9-h protocol was implemented versus 12 and 15 h. The optimal TRE time frame to recommend for people has not been tested. Clear improvements have been noted after 6-, 8-, 9-, and 10-h protocols. It is likely that the greater time restriction would result in greater weight losses, which may maximize the metabolic benefits.

“On a high-sugar diet, we find that the fruit flies’ dopaminergic neurons are less active, because the high sugar intake decreases the intensity of the sweetness signal that comes from the mouth,” Dus said. “Animals use this feedback from dopamine to make predictions about how rewarding or filling a food will be. In the high-sugar diet flies, this process is broken—they get less dopamine neuron activation and so end up eating more than they need, which over time makes them gain weight.”

“On a high-sugar diet, we find that the fruit flies’ dopaminergic neurons are less active, because the high sugar intake decreases the intensity of the sweetness signal that comes from the mouth,” Dus said. “Animals use this feedback from dopamine to make predictions about how rewarding or filling a food will be. In the high-sugar diet flies, this process is broken—they get less dopamine neuron activation and so end up eating more than they need, which over time makes them gain weight.”

The first signs of insufficient sleep are universally familiar. There’s tiredness and fatigue, difficulty concentrating, perhaps irritability or even tired giggles. Far fewer people have experienced the effects of prolonged sleep deprivation, including disorientation, paranoia, and hallucinations.

The first signs of insufficient sleep are universally familiar. There’s tiredness and fatigue, difficulty concentrating, perhaps irritability or even tired giggles. Far fewer people have experienced the effects of prolonged sleep deprivation, including disorientation, paranoia, and hallucinations.