From a New York Times online article (01/02/20):

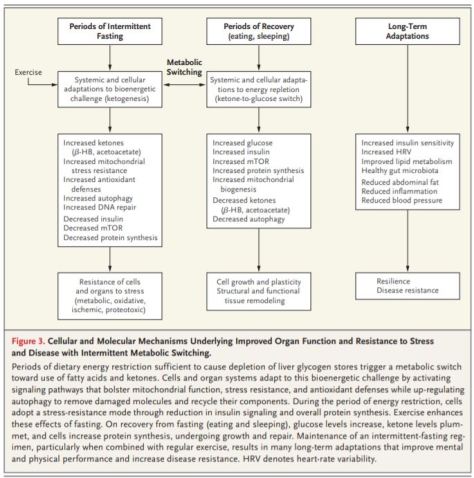

In ways both subtle and substantial, Scorsese sees the world changing and becoming less familiar to him. He gratefully accepted a deal with Netflix, which covered the reported $160 million budget for “The Irishman.” But the bargain meant that, after the movie received a limited theatrical release, it would be shown on the company’s streaming platform.

Scorsese has other aspirations but they have nothing to do with moviemaking. “I would love to just take a year and read,” he said. “Listen to music when it’s needed. Be with some friends. Because we’re all going. Friends are dying. Family’s going.”

Martin Scorsese is the most alive he’s been in his work in a long time, brimming with renewed passion for filmmaking and invigorated by the reception that has greeted his latest gangland magnum opus, “The Irishman.”

And what he wants to talk about is death.

Just to be clear, he’s not talking about the deaths in his movies or anyone else’s. “You just have to let go, especially at this vantage point of age,” he said one Saturday afternoon last month.

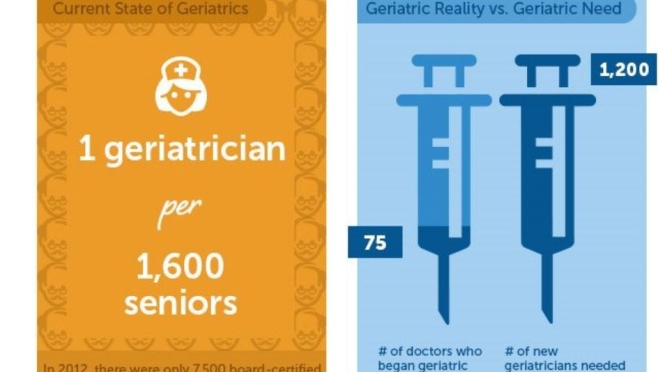

If one geriatrician can care for 700 patients with complicated medical needs,

If one geriatrician can care for 700 patients with complicated medical needs,

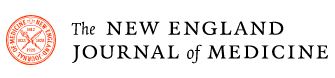

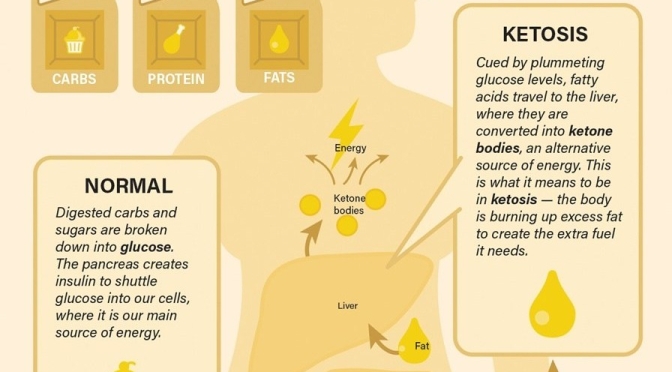

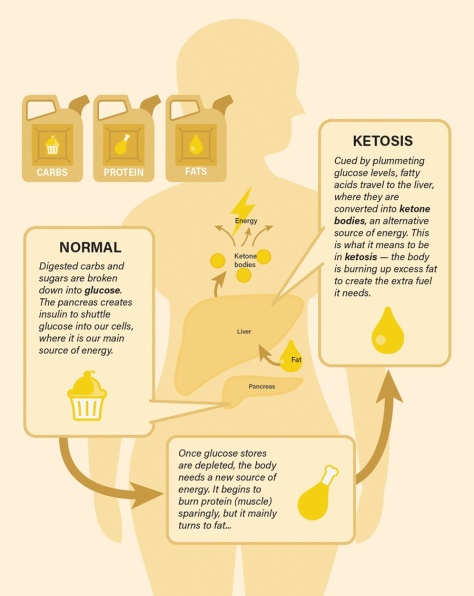

to a paper Mattson and colleagues published in February in the experimental biology journal FASEB. In humans, fasting for 12 hours or more drops the levels of glycogen, a form of cellular glucose. Like changing to a backup gas tank, the body switches from glucose to fatty acids, a more efficient fuel. The switch generates the production of ketones, which are energy molecules that are made in the liver. “When the fats are mobilized and used to produce ketones, we think that is a key factor in accruing the health benefits,” says Mattson.

to a paper Mattson and colleagues published in February in the experimental biology journal FASEB. In humans, fasting for 12 hours or more drops the levels of glycogen, a form of cellular glucose. Like changing to a backup gas tank, the body switches from glucose to fatty acids, a more efficient fuel. The switch generates the production of ketones, which are energy molecules that are made in the liver. “When the fats are mobilized and used to produce ketones, we think that is a key factor in accruing the health benefits,” says Mattson.

Hundreds of miles south of Japan’s main islands, in the East China Sea, is a Jurassic Park of longevity, with a higher percentage of centenarians (people who live to 100 years old) than anywhere else on Earth.

Hundreds of miles south of Japan’s main islands, in the East China Sea, is a Jurassic Park of longevity, with a higher percentage of centenarians (people who live to 100 years old) than anywhere else on Earth.

…the researchers demonstrated that the biggest drop in cognitive ability occurs at the slightest level of hearing loss — a decline from zero to the “normal” level of 25 decibels, with smaller cognitive losses occurring when hearing deficits rise from 25 to 50 decibels.

…the researchers demonstrated that the biggest drop in cognitive ability occurs at the slightest level of hearing loss — a decline from zero to the “normal” level of 25 decibels, with smaller cognitive losses occurring when hearing deficits rise from 25 to 50 decibels. Aging, Duration, and the English Novel argues that the formal disappearance of aging from the novel parallels the ideological pressure to identify as being young by repressing the process of growing old. The construction of aging as a shameful event that should be hidden – to improve one’s chances on the job market or secure a successful marriage – corresponds to the rise of the long novel, which draws upon the temporality of the body to map progress and decline onto the plots of nineteenth-century British modernity.

Aging, Duration, and the English Novel argues that the formal disappearance of aging from the novel parallels the ideological pressure to identify as being young by repressing the process of growing old. The construction of aging as a shameful event that should be hidden – to improve one’s chances on the job market or secure a successful marriage – corresponds to the rise of the long novel, which draws upon the temporality of the body to map progress and decline onto the plots of nineteenth-century British modernity.