Memory

Many studies suggest that exercise can help protect our memory as we age. This is because exercise has been shown to prevent the loss of total brain volume (which can lead to lower cognitive function), as well as preventing shrinkage in specific brain regions associated with memory. For example, one magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan study revealed that in older adults, six months of exercise training increases brain volume.

Another study showed that shrinkage of the hippocampus (a brain region essential for learning and memory) in older people can be reversed by regular walking. This change was accompanied by improved memory function and an increase of the protein brain-derived neutropic factor (BDNF) in the bloodstream.

Blood vessels

The brain is highly dependent on blood flow, receiving approximately 15% of the body’s entire supply – despite being only 2-3% of our body’s total mass. This is because our nervous tissues need a constant supply of oxygen to function and survive. When neurons become more active, blood flow in the region where these neurons are located increases to meet demand. As such, maintaining a healthy brain depends on maintaining a healthy network of blood vessels.

Regular exercise increases the growth of new blood vessels in the brain regions where neurogenesis occurs, providing the increased blood supply that supports the development of these new neurons. Exercise also improves the health and function of existing blood vessels, ensuring that brain tissue consistently receives adequate blood supply to meet its needs and preserve its function.

Inflammation

Recently, a growing body of research has centred on microglia, which are the resident immune cells of the brain. Their main function is to constantly check the brain for potential threats from microbes or dying or damaged cells, and to clear any damage they find.

With age, normal immune function declines and chronic, low-level inflammation occurs in body organs, including the brain, where it increases risk of neurodegenerative disease, such as Alzheimer’s disease. As we age, microglia become less efficient at clearing damage, and less able to prevent disease and inflammation. This means neuroinflammation can progress, impairing brain functions – including memory.

Dr. Stephen Kopecky explains that some people ask to be put on a statin. That’s because statins, while important and effective, are just one part of the whole heart-healthy picture. When you combine a statin with regular exercise, maintaining a healthy weight, controlling stress, not smoking and eating foods based on the Mediterranean diet, you can improve your heart health.

Dr. Stephen Kopecky explains that some people ask to be put on a statin. That’s because statins, while important and effective, are just one part of the whole heart-healthy picture. When you combine a statin with regular exercise, maintaining a healthy weight, controlling stress, not smoking and eating foods based on the Mediterranean diet, you can improve your heart health.

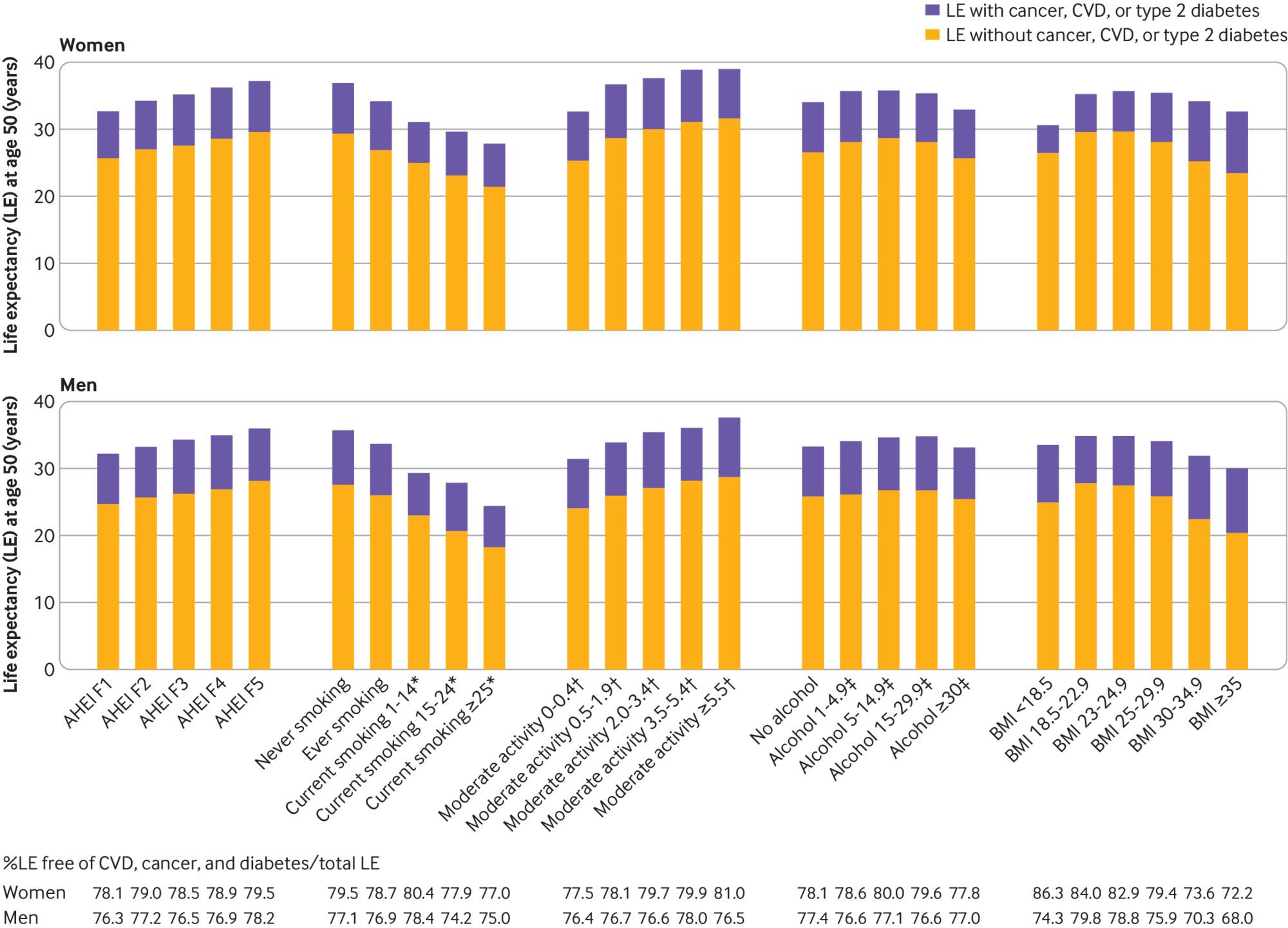

Our findings suggest that promotion of a healthy lifestyle would help to reduce the healthcare burdens through lowering the risk of developing multiple chronic diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes, and extending disease-free life expectancy. Public policies for improving food and the physical environment conducive to adopting a healthy diet and lifestyle, as well as relevant policies and regulations (for example, smoking ban in public places or trans-fat restrictions), are critical to improving life expectancy, especially life expectancy free of major chronic diseases.

Our findings suggest that promotion of a healthy lifestyle would help to reduce the healthcare burdens through lowering the risk of developing multiple chronic diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes, and extending disease-free life expectancy. Public policies for improving food and the physical environment conducive to adopting a healthy diet and lifestyle, as well as relevant policies and regulations (for example, smoking ban in public places or trans-fat restrictions), are critical to improving life expectancy, especially life expectancy free of major chronic diseases.

Copenhagen’s legendary bicycle setup has been propelled by all of these aspirations, but the critical element is the simplest: People here eagerly use their bicycles — in any weather, carrying the young, the infirm, the elderly and

Copenhagen’s legendary bicycle setup has been propelled by all of these aspirations, but the critical element is the simplest: People here eagerly use their bicycles — in any weather, carrying the young, the infirm, the elderly and

Mr. Chambers, a 48-year-old physical therapist in Jersey City, N.J., modified his sleep, diet and exercise routines. Eighteen months later, his performance on a battery of cognitive tests improved, particularly in areas like processing speed and executive function, such as decision-making and planning.

Mr. Chambers, a 48-year-old physical therapist in Jersey City, N.J., modified his sleep, diet and exercise routines. Eighteen months later, his performance on a battery of cognitive tests improved, particularly in areas like processing speed and executive function, such as decision-making and planning.

“A healthy diet and lifestyle are generally recognized as good for health, but this study is the first large randomized controlled trial to look at whether lifestyle changes actually influence Alzheimer’s disease-related brain changes,” said Susan Landau, a research neuroscientist at Berkeley’s Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute, and principal investigator of the add-on study.

“A healthy diet and lifestyle are generally recognized as good for health, but this study is the first large randomized controlled trial to look at whether lifestyle changes actually influence Alzheimer’s disease-related brain changes,” said Susan Landau, a research neuroscientist at Berkeley’s Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute, and principal investigator of the add-on study.