Born in Victoria, Australia, Martin Lewis was a printmaker who is known for his scenes of urban life in New York during the 1920s and 1930s. As a youth Lewis held a variety of jobs that ranged from working on cattle ranches in the Australian Outback, in logging and mining camps, to being a sailor. In 1898, he moved to Sydney for two years where he received his only formal art training. During this period he may have been introduced to printmaking; a local radical paper, The Bulletin, published two of his drawings.

Lewis left Australia in 1900 and first settled in San Francisco. He eventually worked his way eastward to New York. Little is known about his life during the following decade except that he made a living as a commercial artist and produced his first etching in 1915. Lewis’ skill as an etcher was noticed by Edward Hopper, who became a lifelong friend. In 1920, dissatisfied with his job, Lewis used his entire savings to study art and to sketch in Japan. He returned to New York after a two-year stay and resumed his commercial art career, but also pursued his own work as a painter and printmaker.

During the Depression, Lewis moved to Newtown, Connecticut, but later returned to Manhattan, where he helped establish a school for printmakers. From 1944-1952 Lewis taught a graphics course at the Art Students League in New York.

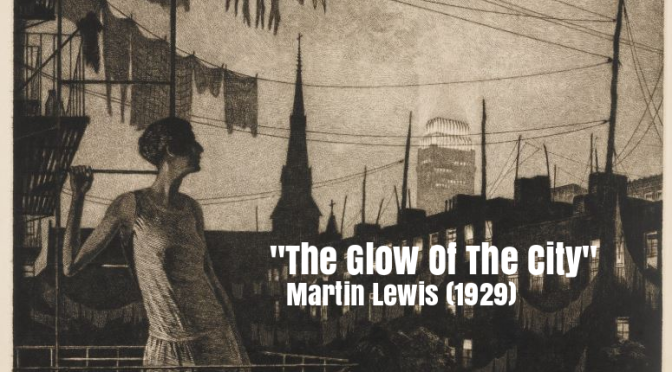

During his thirty-year career, Lewis made about 145 drypoints and etchings. His prints, like Shadow Dance and Stoops in Snow, were much admired during the 1930s for their realistic portrayal of daily life and sensitive rendering of texture. The artist’s skill in composition and his talent in the drypoint and etching media have received renewed attention in recent years. Lewis is one of the few printmakers of this era who specialized in nocturnal scenes. Some scholars consider his print Glow of the City his most significant work because of the subtlety of handling. A minute network of dots, lines, and flecks scratched onto the plate creates the illusion of transparent garments hanging in the foreground, while the Chanin Building, an art deco skyscraper, towers over the nearby tenements.

In his latest publication, Rem Koolhaas explores the rapid and often hidden transformations underway across the Earth’s vast non-urban areas.Countryside, A Report gathers travelogue essays exploring territories marked by global forces and experimentation at the edge of our consciousness: a test site near Fukushima, where the robots that will maintain Japan’s infrastructure and agriculture are tested; a greenhouse city in the Netherlands that may be the origin for the cosmology of today’s countryside; the rapidly thawing permafrost of Central Siberia, a region wrestling with the possibility of relocation; refugees populating dying villages in the German countryside and intersecting with climate change activists; habituated mountain gorillas confronting humans on ‘their’ territory in Uganda; the American Midwest, where industrial-scale farming operations are coming to grips with regenerative agriculture; and Chinese villages transformed into all-in-one factory, e-commerce stores, and fulfillment centers.

In his latest publication, Rem Koolhaas explores the rapid and often hidden transformations underway across the Earth’s vast non-urban areas.Countryside, A Report gathers travelogue essays exploring territories marked by global forces and experimentation at the edge of our consciousness: a test site near Fukushima, where the robots that will maintain Japan’s infrastructure and agriculture are tested; a greenhouse city in the Netherlands that may be the origin for the cosmology of today’s countryside; the rapidly thawing permafrost of Central Siberia, a region wrestling with the possibility of relocation; refugees populating dying villages in the German countryside and intersecting with climate change activists; habituated mountain gorillas confronting humans on ‘their’ territory in Uganda; the American Midwest, where industrial-scale farming operations are coming to grips with regenerative agriculture; and Chinese villages transformed into all-in-one factory, e-commerce stores, and fulfillment centers.

The British Galleries are reopening with almost 700 works of art on view, including a large number of new acquisitions, particularly works from the 19th century that were purchased with this project in mind. This is the first complete renovation of the galleries since they were established (Josephine Mercy Heathcote Gallery in 1986, Annie Laurie Aitken Galleries in 1989). A prominent new entrance provides direct access from the galleries for medieval European art, creating a seamless transition from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance.

The British Galleries are reopening with almost 700 works of art on view, including a large number of new acquisitions, particularly works from the 19th century that were purchased with this project in mind. This is the first complete renovation of the galleries since they were established (Josephine Mercy Heathcote Gallery in 1986, Annie Laurie Aitken Galleries in 1989). A prominent new entrance provides direct access from the galleries for medieval European art, creating a seamless transition from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance. A highlight of The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 150th anniversary in 2020 is the opening, on March 2, of the Museum’s newly installed Annie Laurie Aitken Galleries and Josephine Mercy Heathcote Gallery—11,000 square feet devoted to British decorative arts, design, and sculpture created between 1500 and 1900. The reimagined suite of 10 galleries (including three superb 18th-century interiors) provides a fresh perspective on the period, focusing on its bold, entrepreneurial spirit and complex history. The new narrative offers a chronological exploration of the intense commercial drive among artists, manufacturers, and retailers that shaped British design over the course of 400 years. During this period, global trade and the growth of the British Empire fueled innovation, industry, and exploitation. Works on view illuminate the emergence of a new middle class—ready consumers for luxury goods—which inspired an age of exceptional creativity and invention during a time of harsh colonialism.

A highlight of The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 150th anniversary in 2020 is the opening, on March 2, of the Museum’s newly installed Annie Laurie Aitken Galleries and Josephine Mercy Heathcote Gallery—11,000 square feet devoted to British decorative arts, design, and sculpture created between 1500 and 1900. The reimagined suite of 10 galleries (including three superb 18th-century interiors) provides a fresh perspective on the period, focusing on its bold, entrepreneurial spirit and complex history. The new narrative offers a chronological exploration of the intense commercial drive among artists, manufacturers, and retailers that shaped British design over the course of 400 years. During this period, global trade and the growth of the British Empire fueled innovation, industry, and exploitation. Works on view illuminate the emergence of a new middle class—ready consumers for luxury goods—which inspired an age of exceptional creativity and invention during a time of harsh colonialism.

What was the world like from 500 to 1500 CE? This period, often called medieval or the Middle Ages in European history, saw the rise and fall of empires and the expansion of cross-cultural exchange.

What was the world like from 500 to 1500 CE? This period, often called medieval or the Middle Ages in European history, saw the rise and fall of empires and the expansion of cross-cultural exchange.