How Arizona’s microschool boom is reshaping the American classroom—and reviving old questions about freedom, equity, and the gaze of the state.

By Michael Cummins, Editor, August 21, 2025

Jeremy Bentham never saw his panopticon built. The English philosopher imagined a circular prison with a central watchtower, where a single guard could observe every inmate without being seen. Bentham saw it as a triumph of efficiency: if prisoners could never know when they were being watched, they would behave as though they always were. A century later, Michel Foucault seized on the design as metaphor. In Discipline and Punish, he argued that the panopticon revealed the true mechanics of modern institutions—not brute force, but the internalization of surveillance. The gaze becomes ambient. The subject becomes self-regulating.

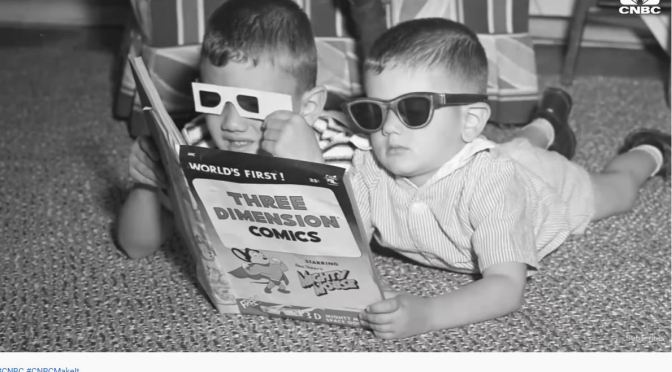

This, in many ways, is the story of the American public school. The common school movement of the mid-nineteenth century, led by Horace Mann, sought standardization: children from Boston to St. Louis would recite the same lessons, read the same primers, and adopt the same civic habits. As cities grew, schools scaled up. By the twentieth century, especially in the wake of A Nation at Risk, the classroom had become a site of discipline. Bells regulated time. Grades ranked performance. Administrators patrolled hallways like wardens. Testing regimes quantified ability. The metaphor was not lost on Foucault. Brown University notes that his vision of the panopticon extended beyond prisons to schools: a “system of surveillance where individuals internalize the feeling of being constantly watched, leading to self-regulation of behavior” (Brown University).

Every American child knows this regime. The bell rings. The roll is called. The test is bubbled and scanned. Hall passes are signed like parole slips. Cameras blink in cafeteria corners. Laptops carry software that tracks keystrokes. Even silence becomes an instrument of order.

Bentham saw efficiency. Foucault saw discipline. Students often see only the weight of the watchtower.

What happens when families walk out of the circle?

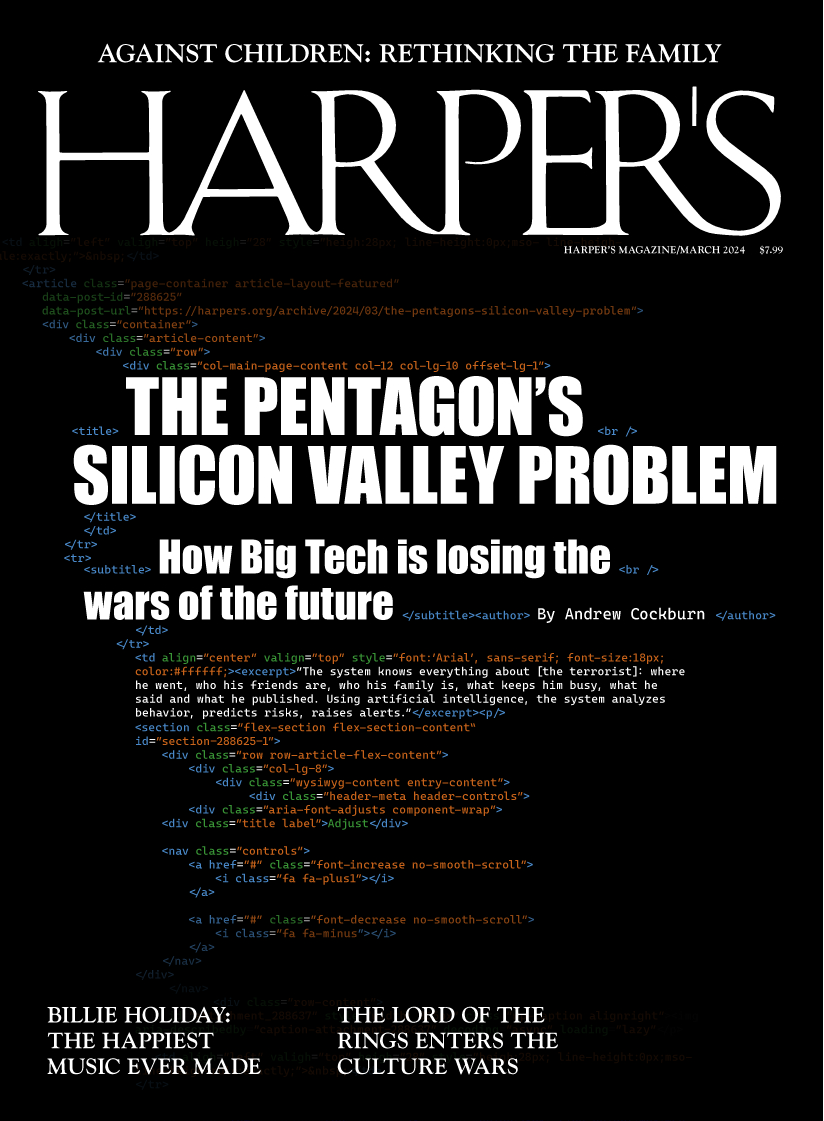

In the far suburbs of Phoenix, on the edge of the White Tank Mountains, a converted casita serves as the Refresh Learning Center. Founded in 2023 by a pastor and his wife, it doesn’t look like much—aluminum siding, recycled chairs, a wall chart that places the birth of the universe at 4004 B.C. Yet, as Chandler Fritz wrote in the September 2025 issue of Harper’s Magazine, the little school has become an emblem of a movement reshaping American education.

Its existence rests on a radical policy shift. In 2022, Arizona launched the nation’s most expansive Empowerment Scholarship Account (ESA) program. Unlike traditional vouchers, which could be redeemed only at approved institutions, ESA funds flow directly to parents—roughly $7,500 per student, sometimes more. Families can spend the money on almost anything that counts as “educational”: a cello, a VR headset, a trampoline, or, increasingly, a place in one of the microschools sprouting across the state.

The metaphor of the frontier clings naturally to Arizona. Here, in the desert’s glare, families are homesteading education in much the same spirit as settlers once claimed land. A garage becomes a classroom. A supply closet, a high school. A church basement, an academy. In his Harper’s piece, Fritz describes a child attending class in a room where chickens wandered the yard outside, and another high-school seminar meeting in a closet stacked with supply boxes. Parents pull their children not only for ideology but for intimacy, pace, or simple safety. “Without ESA, this school would not—could not—exist,” one founder told him.

For advocates, the program represents liberation from a failing system. For critics, it siphons resources from public schools already parched of funding. But for the families gathered in little schoolhouses like Refresh, the stakes feel simpler: children freed from the gaze of bureaucracy, from endless testing and administrative oversight, given room to learn like human beings again.

Microschools are not new. Before the rise of the common school, most American children learned in homes, barns, or one-room cabins where a single teacher instructed a dozen children of all ages. Reformers dismissed those spaces as unsystematic, unjust. The standardized school, they argued, would correct inequities and prepare citizens for democracy.

Today, the pendulum swings back. Inside Refresh’s aluminum-sided room, teenagers do crafts next to six-year-olds. Grade levels blur: a thirteen-year-old may still be in second grade; another, the same age, reads at a high school level. Students spend mornings mucking chicken coops and afternoons in shop class. A boy named Aaron, dyslexic and restless in traditional schools, thrives in the workshop, building desks and repairing tools. He dreams of becoming an Air Force mechanic. One teacher observed that he learned fractions by cutting lumber and measuring shelves—mathematics discovered in wood grain and sawdust.

Another student, Hailey, is quick with skepticism. She listens to indie rock from her AirPods between classes, balances her faith with her friendships, and rolls her eyes at biblical literalism. “Stop comparing everything to religion,” she wrote in a survey. “I know it’s a Christian school, but it’s annoying learning about history when it’s asking about the Bible.”

And then there is Canaan, a foster child, the oldest in the room. During a discussion of To Kill a Mockingbird, he startled his peers by pressing the point of segregation. “What if everyone were actually given the same resources?” he asked. The question, naïve and profound, echoed the legal logic of Brown v. Board of Education, though he had never heard of it. His teachers had worried about whether he was “ready” for a seminar text. Yet here he was, articulating the problem of equality with more clarity than many adults.

Their stories recall sepia-toned photographs of America’s one-room schoolhouses, where a teacher might balance a baby on one hip while drilling older students in long division. Nostalgia clings to such places, but for children like Aaron and Hailey and Canaan, the sense of being known—of not being lost in the machinery of standardization—is more than nostalgia. It is survival.

The ESA marketplace, though, has the volatility of a boomtown. Alongside earnest shop classes and backyard literature circles, Fritz encountered vendors offering tongue-posture therapy for ADHD, pirate-themed cooking classes tied to multilevel marketing schemes, even sword-making courses. In one Tucson suburb, a “Kids in the Kitchen” class doubled as an advertisement for a health supplement brand. Fraud has siphoned hundreds of thousands of dollars from taxpayers (Arizona Central).

More troubling is fragmentation. Public schools, for all their flaws, force pluralism: children from different families, faiths, and incomes learning together under one roof. In microschools, communities splinter. Wealthier families claim ESA funds for private tuition; poorer families scrape together what they can. Evangelical churches convert Sunday schools into full-time academies. A Southern Baptist initiative now urges every church with a basement to consider opening a weekday school. For some, ESAs represent not escape from the panopticon, but an opportunity to build new watchtowers of ideological oversight.

And yet—the children remain. Their stories suggest that the most powerful escape is not from testing regimes or surveillance, but from anonymity. In a one-room schoolhouse, a teacher cannot forget you. Your hands matter. Your questions land. You are not a datapoint in a dashboard but a voice in a circle.

The paradox of the new homestead is that it is subsidized by the very state it seeks to escape. Every ESA contract is drawn from public funds, even as public schools wither under declining enrollment and teacher shortages. Arizona’s superintendent warned in 2024 that the state’s teacher shortage, already in the thousands, could “eventually lead to zero teachers” (Arizona Policy). Meanwhile, parents swipe ESA debit cards for pianos, VR headsets, or ski passes.

But the deeper paradox is philosophical. The panopticon teaches that institutions discipline by watching. Yet children, it turns out, discipline themselves when unseen, too. In one seminar, Canaan insisted that segregation was the true injustice, not just a false verdict. Without oversight, a conversation about reparations and justice unfolded around plastic tables in a desert conversation.

Could it be that the very fragmentation critics fear might also produce unexpected awakenings? That freedom from the gaze of the state could allow children to stumble, clumsily but genuinely, into civic consciousness?

The question is not whether microschools should exist—they already do, enrolling as many students as Catholic schools nationwide. The question is how to balance their intimacy with the democratic promise of education for all. Some states experiment with guardrails: Georgia ties funds to low-performing districts; Iowa requires accreditation and assessments. Arizona, the boldest frontier, remains laissez-faire. The experiment is still young, and the stakes enormous.

Bentham dreamed of efficiency. Foucault warned of discipline. But neither accounted for what happens when the watchtower is abandoned, when families strike out into the desert to build little schools of their own. The panopticon dissolves, and in its place rises the homestead, the one-room schoolhouse, the handmade desk, the boy who lights up in shop class.

Public education was once America’s grandest democratic experiment: the poor man could reach into the rich man’s pocket and demand an education, as Emerson put it, “not as you will, but as I will” (Ralph Waldo Emerson, Education). That dream is endangered—not only by privatization, but by the creeping sense that children are means rather than ends, data points rather than persons.

The frontier metaphor cuts both ways. It can justify privatization, sectarianism, inequality. But it also gestures toward freedom, self-reliance, discovery. The challenge now is to reclaim the best of the homestead spirit—education as intimate, child-centered, alive—without abandoning the pluralistic commons that democracy requires.

Wallace Stegner once called life on the frontier a “homemade education.” He meant not only the Bible lessons of pioneer families but the curriculum of the land itself—children learning resilience from drought, ingenuity from scarcity, curiosity from the wide sky. The graduates of such an education—Lincoln, Twain, Cather, John Wesley Powell—proved that learning could be stitched together from books, rivers, and conversation. Powell, chastised in school for his parents’ abolitionist views, was pulled from the classroom and tutored privately. He learned geology by picking up stones, ornithology by watching birds, justice by watching neighbors turn cruel. The lessons carried him down the Colorado River, into history.

Perhaps the future lies not in the panopticon or the homestead alone, but in something more fluid: a system where every child is seen not from above, but up close. Where accountability measures ensure equity without strangling individuality. Where the workshop and the test, the prayer and the debate, the child who loves Jesus and the child who loves indie rock can share the same fragile, human classroom.

Education is not a prison, nor a frontier settlement. It is, at its best, a river: wide enough to carry all, winding enough to follow curiosity, strong enough to shape the land it touches. The question is whether we will keep damming it with watchtowers—or whether we will learn, finally, to let it flow.

THIS ESSAY WAS WRITTEN AND EDITED UTILIZING AI