By Michael Cummins, Editor, August 7, 2025

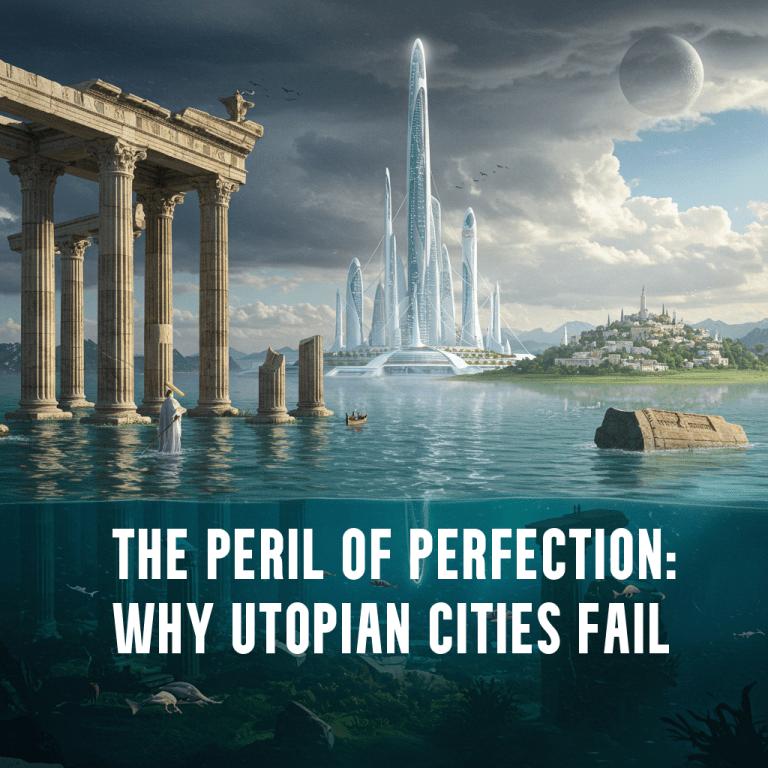

Throughout human history, the idea of a perfect city—a harmonious, orderly, and just society—has been a powerful and enduring dream. From the philosophical blueprints of antiquity to the grand, state-sponsored projects of the modern era, the desire to create a flawless urban space has driven thinkers and leaders alike. This millennia-long aspiration, rooted in a fundamental human longing for order and a rejection of present-day flaws, finds its most recent and monumental expression in China’s Xiongan New Area, a project highlighted in an August 7, 2025, Economist article titled “Xi Jinping’s city of the future is coming to life.” Xiongan is both a marvel of technological and urban design and a testament to the persistent—and potentially perilous—quest for an idealized city.

By examining the historical precedents of utopian thought, we can understand Xiongan not merely as a contemporary infrastructure project but as the latest chapter in a timeless and often fraught human ambition to build paradise on earth. This essay will trace the evolution of the utopian ideal from ancient philosophy to modern practice, arguing that while Xiongan embodies the most technologically advanced and politically ambitious vision to date, its top-down, state-driven nature and astronomical costs raise critical questions about its long-term viability and ability to succeed where countless others have failed.

The Philosophical and Historical Roots

The earliest and most iconic examples of this utopian desire were theoretical and philosophical, serving as intellectual critiques rather than practical blueprints. Plato’s mythological city of Atlantis, described in his dialogues Timaeus and Critias, was not just a lost city but a complex philosophical thought experiment. Plato detailed a powerful, technologically advanced, and ethically pure island society, governed by a wise and noble lineage. The city itself was a masterpiece of urban planning, with concentric circles of land and water, advanced canals, and stunning architecture.

However, its perfection was ultimately undone by human greed and moral decay. As the Atlanteans became corrupted by hubris and ambition, their city was swallowed by the sea. This myth is foundational to all subsequent utopian thought, serving as a powerful and enduring cautionary tale that even the most perfect physical and social structure is fragile and susceptible to corruption from within. It suggests that a utopian society cannot simply be built; its sustainability is dependent on the moral fortitude of its citizens.

Centuries later, in 1516, Thomas More gave the concept its very name with his book Utopia. More’s work was a masterful social and political satire, a searing critique of the harsh realities of 16th-century England. He described a fictional island society where there was no private property, and all goods were shared. The citizens worked only six hours a day, with the rest of their time dedicated to education and leisure.

“For where pride is predominant, there all these good laws and policies that are designed to establish equity are wholly ineffectual, because this monster is a greater enemy to justice than avarice, anger, envy, or any other of that kind; and it is a very great one in every man, though he have never so much of a saint about him.” – Utopia by Thomas More

The society was governed by reason and justice, and there were no social classes, greed, or poverty. More’s Utopia was not about a perfect physical city, but a perfect social structure. It was an intellectual framework for political philosophy, designed to expose the flaws of a European society plagued by poverty, inequality, and the injustices of land enclosure. Like Atlantis, it existed as an ideal, a counterpoint to the flawed present, but it established a powerful cultural archetype.

The city as a reflection of societal ideals. — Intellicurean

Following this, Francis Bacon’s unfinished novel New Atlantis (1627) offered a different, more prophetic vision of perfection. His mythical island, Bensalem, was home to a society dedicated not to social or political equality, but to the pursuit of knowledge. The core of their society was “Salomon’s House,” a research institution where scientists worked together to discover and apply knowledge for the benefit of humanity. Bacon’s vision was a direct reflection of his advocacy for the scientific method and empirical reasoning.

In his view, a perfect society was one that systematically harnessed technological innovation to improve human life. Bacon’s utopia was a testament to the power of collective knowledge, a vision that, unlike More’s, would resonate profoundly with the coming age of scientific and industrial revolution. These intellectual exercises established a powerful cultural archetype: the city as a reflection of societal ideals.

From Theory to Practice: Real-World Experiments

As these ideas took root, the dream of a perfect society moved from the page to the physical world, often with mixed results. The Georgia Colony, founded in 1732 by James Oglethorpe, was conceived with powerful utopian ideals, aiming to be a fresh start for England’s “worthy poor” and debtors. Oglethorpe envisioned a society without the class divisions that plagued England, and to that end, his trustees prohibited slavery and large landholdings. The colony was meant to be a place of virtue, hard work, and abundance. Yet, the ideals were not fully realized. The prohibition on slavery hampered economic growth compared to neighboring colonies, and the trustees’ rules were eventually overturned. The colony ultimately evolved into a more typical slave-holding, plantation-based society, demonstrating how external pressures and economic realities can erode even the most virtuous of founding principles.

In the 19th century, with the rise of industrialization, several communities were established to combat the ills of the new urban landscape. The Shakers, a religious community founded in the 18th century, are one of America’s most enduring utopian experiments. They built successful communities based on communal living, pacifism, gender equality, and celibacy. Their belief in simplicity and hard work led to a reputation for craftsmanship, particularly in furniture making. At their peak in the mid-19th century, there were over a dozen Shaker communities, and their economic success demonstrated the viability of communal living. However, their practice of celibacy meant they relied on converts and orphans to sustain their numbers, a demographic fragility that ultimately led to their decline. The Shaker experience proved that a society’s success depends not only on its economic and social structure but also on its ability to sustain itself demographically.

These real-world attempts demonstrate the immense difficulty of sustaining a perfect society against the realities of human nature and economic pressures. — Intellicurean

The Transcendentalist experiment at Brook Farm (1841-1847) attempted to blend intellectual and manual labor, blurring the lines between thinkers and workers. Its members, who included prominent figures like Nathaniel Hawthorne, believed that a more wholesome and simple life could be achieved in a cooperative community. However, the community struggled from the beginning with financial mismanagement and the impracticality of their ideals. The final blow was a disastrous fire that destroyed a major building, and the community was dissolved. Brook Farm’s failure illustrates a central truth of many utopian experiments: idealism can falter in the face of economic pressures and simple bad luck.

A more enduring but equally radical experiment, the Oneida Community (1848-1881), achieved economic success through manufacturing, particularly silverware, under the leadership of John Humphrey Noyes. Based on his concept of “Bible Communism,” they practiced communal living and a system of “complex marriage.” Despite its radical social structure, the community thrived economically, but internal disputes and external pressures ultimately led to its dissolution. These real-world attempts demonstrate the immense difficulty of sustaining a perfect society against the realities of human nature and economic pressures.

Xiongan: The Modern Utopia?

Xiongan is the natural, and perhaps ultimate, successor to these modern visions. It represents a confluence of historical utopian ideals with a uniquely contemporary, state-driven model of urban development. Touted as a “city of the future,” Xiongan promises short, park-filled commutes and a high-tech, digitally-integrated existence. It seeks to be a model of ecological civilization, where 70% of the city is dedicated to green space and water, an explicit rejection of the “urban maladies” of pollution and congestion that plague other major Chinese cities.

Its design principles are an homage to the urban planners of the past, with a “15-minute lifecycle” for residents, ensuring all essential amenities are within a short walk. The city’s digital infrastructure is also a modern marvel, with digital roads equipped with smart lampposts and a supercomputing center designed to manage the city’s traffic and services. In this sense, Xiongan is a direct heir to Francis Bacon’s vision of a society built on scientific and technological progress.

Unlike the organic, market-driven growth of a city like Shenzhen, Xiongan is an authoritarian experiment in building a perfect city from scratch. — The Economist

This vision, however, is a top-down creation. As a “personal initiative” of President Xi, its success is a matter of political will, with the central government pouring billions into its construction. The project is a key part of the “Jing-Jin-Ji” (Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei) coordinated development plan, meant to relieve the pressure on the capital. Unlike the organic, market-driven growth of a city like Shenzhen, Xiongan is an authoritarian experiment in building a perfect city from scratch. Shenzhen, for example, was an SEZ (Special Economic Zone) that grew from the bottom up, driven by market forces and a flexible policy environment. It was a chaotic, rapid, and often unplanned explosion of economic activity. Xiongan, in stark contrast, is a meticulously planned project from its very inception, with a precise ideological purpose to showcase a new kind of “socialist” urbanism.

This centralized approach, while capable of achieving rapid and impressive infrastructure development, runs the risk of failing to create the one thing a true city needs: a vibrant, organic, and self-sustaining culture. The criticisms of Xiongan echo the failures of past utopian ventures; despite the massive investment, the city’s streets remain “largely empty,” and it has struggled to attract the talent and businesses needed to become a bustling metropolis. The absence of a natural community and the reliance on forced relocations have created a city that is technically perfect but socially barren.

The Peril of Perfection

The juxtaposition of Xiongan with its utopian predecessors highlights the central tension of the modern planned city. The ancient dream of Atlantis was a philosophical ideal, a perfect society whose downfall served as a moral warning against hubris. The real-world communities of the 19th century demonstrated that idealism could falter in the face of economic and social pressures, proving that a perfect society is not a fixed state but a dynamic, and often fragile, process. The modern reality of Xiongan is a physical, political, and economic gamble—a concrete manifestation of a leader’s will to solve a nation’s problems through grand design. It is a bold attempt to correct the mistakes of the past and a testament to the immense power of a centralized state. Yet, the question remains whether it can escape the fate of its predecessors.

The ultimate verdict on Xiongan will not be about the beauty of its architecture or the efficiency of its smart infrastructure alone, but whether it can successfully transcend its origins as a state project. — The Economist

The ultimate verdict on Xiongan will not be about the beauty of its architecture or the efficiency of its smart infrastructure alone, but whether it can successfully transcend its origins as a state project to become a truly livable, desirable, and thriving city. Only then can it stand as a true heir to the timeless dream of a perfect urban space, rather than just another cautionary tale. Whether a perfect city can be engineered from the top down, or if it must be a messy, organic creation, is the fundamental question that Xiongan, and by extension, the modern world, is attempting to answer.

THIS ESSAY WAS WRITTEN AND EDITED UTILIZING AI