The world now faces the threat of a second wave of coronavirus outbreaks. Zanny Minton Beddoes, The Economist’s editor-in-chief, and Slavea Chankova, our health-care correspondent, answer your questions.

The world now faces the threat of a second wave of coronavirus outbreaks. Zanny Minton Beddoes, The Economist’s editor-in-chief, and Slavea Chankova, our health-care correspondent, answer your questions.

Public health experts think Covid-19 risk is lower outside, and restaurateurs want to fill tables. It’s an easy solution—except for all the hard parts.

Public health experts think Covid-19 risk is lower outside, and restaurateurs want to fill tables. It’s an easy solution—except for all the hard parts.“In a restaurant operating on the typical dining model of table service, I have not yet seen a case where outdoor seating would make up for the amount of lost indoor seating due to distancing,” Boor says. “Even the ones that come close require some pretty big assumptions about making that outdoor seating usable, like building something like wind screens and heating elements.” Few cities in the US have year-round pleasant weather in the evenings, whether that’s because of heat, humidity, cold, or rain. So restaurants trying to expand their borders are going to have to build some kind of nimbus of infrastructure to minimize the picnic-in-the-rain vibe. Of course, the more enclosed an outdoor space is, the more it is like an indoor space—with all the concomitant risks.

From Scientific American (June 23, 2020):

In fact, research on actual cases, as well as models of the pandemic, indicate that between 10 and 20 percent of infected people are responsible for 80 percent of the coronavirus’s spread.

In fact, research on actual cases, as well as models of the pandemic, indicate that between 10 and 20 percent of infected people are responsible for 80 percent of the coronavirus’s spread.

Researchers have identified several factors that make it easier for superspreading to happen. Some of them are environmental.

Through homemade maps, CityLab readers shared perspectives and stories from a world transformed by the coronavirus pandemic.

The Wall Street Journal looks at how air travel will change and what it will be like to fly after the pandemic.

The Wall Street Journal looks at how air travel will change and what it will be like to fly after the pandemic.

Staff Writer Kelly Servick joins host Sarah Crespi to talk about the ins and outs of coronavirus contact tracing apps—what they do, how they work, and how to calculate whether they are crushing the curve.

Staff Writer Kelly Servick joins host Sarah Crespi to talk about the ins and outs of coronavirus contact tracing apps—what they do, how they work, and how to calculate whether they are crushing the curve. Edward Gregr, a postdoctoral fellow at the Institute for Resources, Environment, and Sustainability at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, talks with Sarah about the controversial reintroduction of sea otters to the Northern Pacific Ocean—their home for centuries, before the fur trade nearly wiped out the apex predator in the late 1800s. Gregr brings a unique cost-benefit perspective to his analysis, and finds many trade-offs with economic implications for fisheries For example, sea otters eat shellfish like urchins and crabs, depressing the shellfishing industry; but their diet encourages the growth of kelp forests, which in turn provide a habitat for economically important finfish, like salmon and rockfish.

From the Wall Street Journal (June 8, 2020):

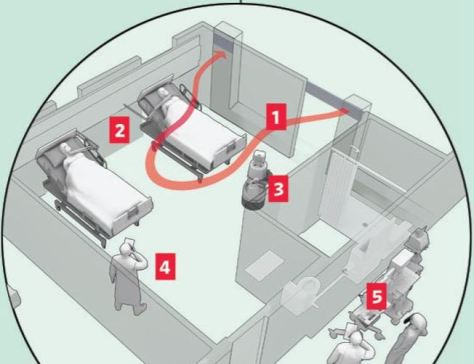

“We have to operate a hospital within a hospital, taking care of the needs for patients who have had strokes or a newborn delivery or need surgery while dealing with an otherwise healthy 35-year-old who picked up Covid-19 at a social event,” says James Linder, chief executive of Nebraska Medicine…

For instance, more hospitals are remotely triaging and registering patients before they even arrive. Clinicians can consult with patients from their home via telemedicine to help determine how sick they are and if they need to come to the ER at all. From there, admissions are made with as little contact with staff or other patients as possible.

For instance, more hospitals are remotely triaging and registering patients before they even arrive. Clinicians can consult with patients from their home via telemedicine to help determine how sick they are and if they need to come to the ER at all. From there, admissions are made with as little contact with staff or other patients as possible.

Hospitals are rethinking how they operate in light of the Covid-19 pandemic—and preparing for a future where such crises may become a grim fact of life.

With the potential for resurgences of the coronavirus, and some scientists warning about outbreaks of other infectious diseases, hospitals don’t want to be caught flat-footed again. So, more of them are turning to new protocols and new technology to overhaul standard operating procedure, from the time patients show up at an emergency room through admission, treatment and discharge.

With the potential for resurgences of the coronavirus, and some scientists warning about outbreaks of other infectious diseases, hospitals don’t want to be caught flat-footed again. So, more of them are turning to new protocols and new technology to overhaul standard operating procedure, from the time patients show up at an emergency room through admission, treatment and discharge.

First up this week, Staff Writer Meredith Wadman talks with host Sarah Crespi about how male sex hormones may play a role in higher levels of severe coronavirus infections in men. New support for this idea comes from a study showing high levels of male pattern baldness in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

First up this week, Staff Writer Meredith Wadman talks with host Sarah Crespi about how male sex hormones may play a role in higher levels of severe coronavirus infections in men. New support for this idea comes from a study showing high levels of male pattern baldness in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Next, Jason Qian, a Ph.D. student in the systems biology department at Harvard Medical School, joins Sarah to talk about an object-tracking system that uses bacterial spores engineered with unique DNA barcodes. The inactivated spores can be sprayed on anything from lettuce, to wood, to sand and later be scraped off and read out using a CRISPR-based detection system. Spraying these DNA-based identifiers on such things as vegetables could help trace foodborne illnesses back to their source. Read a related commentary piece.