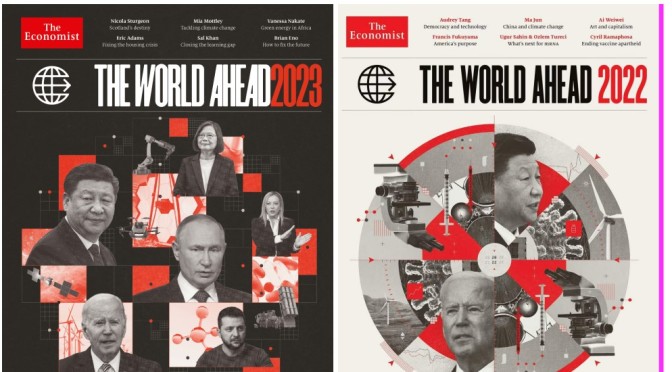

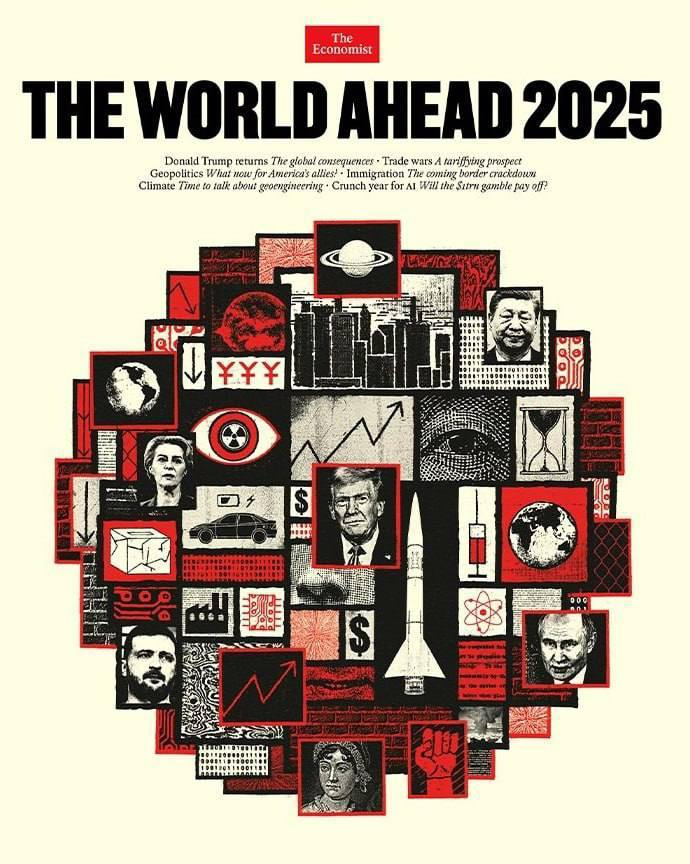

The Economist The World Ahead 2026 (November 13, 2025):

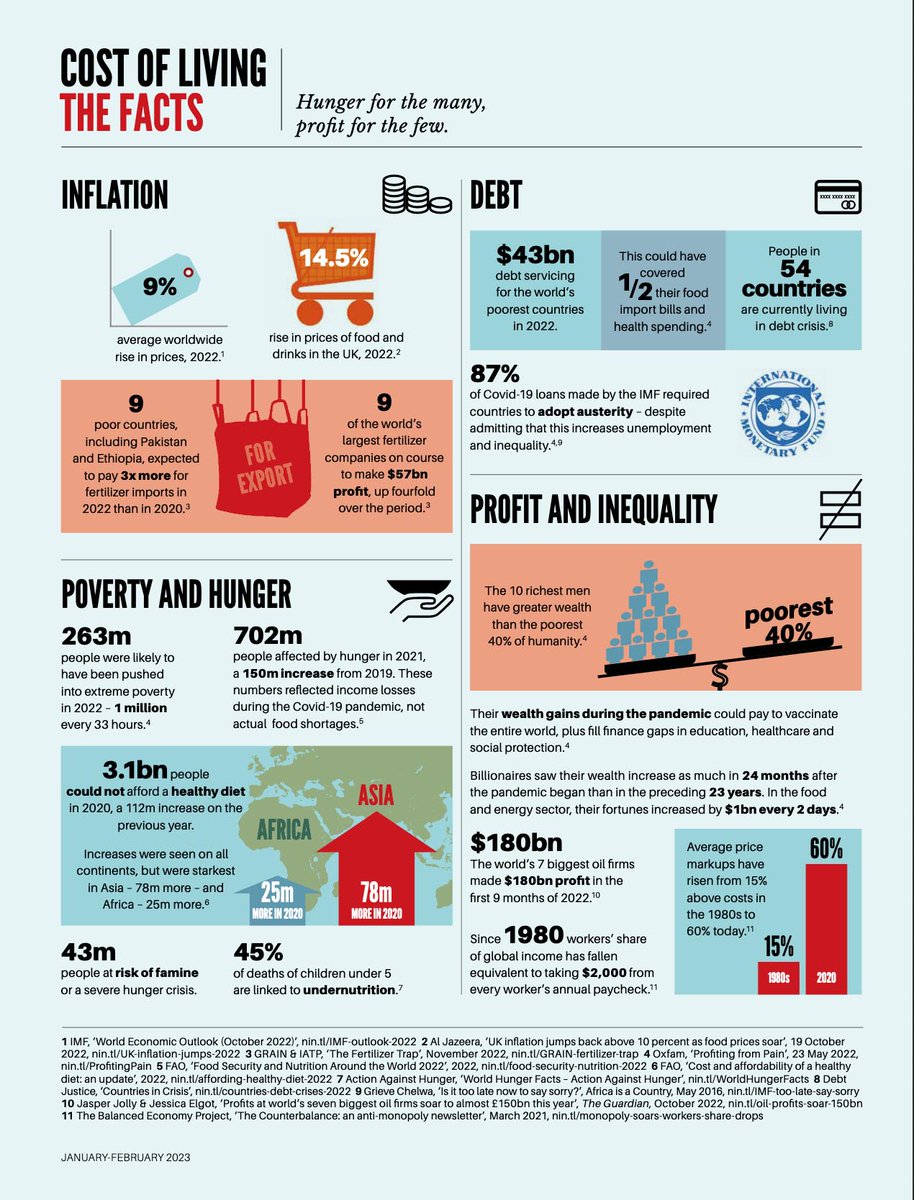

This is Donald Trump’s world—we’re all just living in it. The disruptor-in-chief was the biggest factor shaping global affairs in 2025, and that will be the case for as long as he remains in the White House. His norm-shattering approach has caused turmoil in some areas (as in trade) but has also delivered diplomatic results (as in Gaza) and forced necessary change (as with European defence spending). As the Trumpnado spins on in 2026, here are ten trends and themes to watch in the coming year.

Expect to hear wildly diverging accounts of America’s past, present and future, as Republicans and Democrats describe the same country in irreconcilably different terms to mark the 250th anniversary of its founding. Voters will then give their verdict on America’s future in the midterm elections in November. But even if the Democrats take the House, Mr Trump’s rule by bullying, tariffs and executive orders will go on.

Foreign-policy analysts are divided: is the world in a new cold war, between blocs led by America and China, or will a Trumpian deal divide the planet into American, Russian and Chinese “spheres of influence”, in which each can do as they please? Don’t count on either. Mr Trump prefers a transactional approach based on instinct, not grand geopolitical paradigms. The old global rules-based order will drift and decay further. But “coalitions of the willing” will strike new deals in areas such as defence, trade and climate.

With luck, the fragile peace in Gaza will hold. But conflicts will grind on in Ukraine, Sudan and Myanmar. Russia and China will test America’s commitment to its allies with “grey-zone” provocations in northern Europe and the South China Sea. As the line between war and peace becomes ever more blurred, tensions will rise in the Arctic, in orbit, on the sea floor and in cyberspace.

All this poses a particular test for Europe. It must increase defence spending, keep America on side, boost economic growth and deal with huge deficits, even though austerity risks stoking support for hard-right parties. It also wants to remain a leading advocate for free trade and greenery. It cannot do all of these at once. A splurge on defence spending may lift growth, but only slightly.

China has its own problems, with deflation, slowing growth and an industrial glut, but Mr Trump’s “America First” policy opens up new opportunities for China to boost its global influence. It will present itself as a more reliable partner, particularly in the global south, where it is striking a string of trade agreements. It is happy to do tactical deals with Mr Trump on soyabeans or chips. The trick will be to keep relations with America transactional, not confrontational.With rich countries living beyond their means, the risk of a bond-market crisis is growing

So far America’s economy is proving more resilient than many expected to Mr Trump’s tariffs, but they will dampen global growth. And with rich countries living beyond their means, the risk of a bond-market crisis is growing. Much will depend on the replacement of Jerome Powell as chair of the Federal Reserve in May; politicising the Fed could trigger a market showdown.

Rampant spending on infrastructure for artificial intelligence may also be concealing economic weakness in America. Will the bubble burst? As with railways, electricity and the internet, a crash would not mean that the technology does not have real value. But it could have wide economic impact. Either way, concern about AI’s impact on jobs, particularly those of graduates, will deepen.

Limiting warming to 1.5°C is off the table, and Mr Trump hates renewables. But global emissions have probably peaked, clean tech is booming across the global south and firms will meet or exceed their climate targets—but will keep quiet about it to avoid Mr Trump’s ire. Geothermal energy is worth watching.

Sport can always be relied upon to provide a break from politics, right? Well, maybe not in 2026. The football World Cup is being jointly hosted by America, Canada and Mexico, whose relations are strained. Fans may stay away. But the Enhanced Games, in Las Vegas, may be even more controversial: athletes can use performance-enhancing drugs. Is it cheating—or just different?

Better, cheaper GLP-1 weight-loss drugs are coming, and in pill form, too. That will expand access. But is taking them cheating? GLP-1s extend the debate about the ethics of performance-enhancing drugs to a far wider group than athletes or bodybuilders. Few people compete in the Olympics. But anyone can take part in the Ozempic games.