Plastic has become a malevolent symbol of our wasteful society. It’s also one of the most successful materials ever invented: it’s cheap, durable, flexible, waterproof, versatile, lightweight, protective and hygienic.

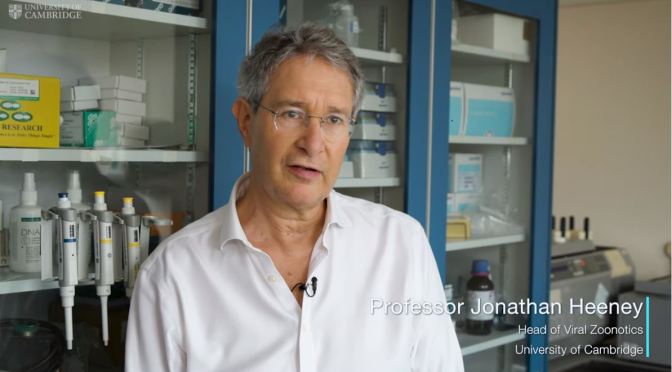

During the coronavirus pandemic, plastic visors, goggles, gloves and aprons have been fundamental for protecting healthcare workers from the virus. But what about the effects on the environment of throwing away huge numbers of single-use medical protection equipment? How are we to balance our need for plastic with protecting the environment?

Delayed as a result of the pandemic, the film is being released now because it considers how society might ‘reset the clock’ when it comes to living better with a vital material.

We hear how Cambridge University’s Cambridge Creative Circular Plastics Centre (CirPlas) aims to eliminate plastic waste by combining blue-sky thinking with practical measures – from turning waste plastic into hydrogen fuel, to manufacturing more sustainable materials, to driving innovations in plastic recycling in a circular economy.

“As a chemist I look at plastic and I see an extremely useful material that is rich in chemicals and energy – a material that shouldn’t end up in landfills and pollute the environment,” says Professor Erwin Reisner, who leads CirPlas, funded by UK Research and Innovation.

“Plastic is an example of how we must find ways to use resources without irreversibly changing the planet for future generations.”

Explore more: CirPlas: https://www.energy.cam.ac.uk/Plastic_…

ABOUT THE MOTION: This House Prefers Reading Oscar Wilde to George Orwell Do we prefer satire or comedy? Do we take refuge in the serious or the frivolous? Do we understand the importance of being earnest or would we rather be in room 101? These two authors demonstrate well two powerful traditions in British literature, the comic and the satirical. They both of course share in each other’s art. Some would argue that during our present global crises we should look to Orwell more than ever, others would reach for the escapism of Oscar Wilde. In a new enterprise for the Cambridge Union, we are beginning our cultural debates – and this is our first. At least for a while.

ABOUT THE MOTION: This House Prefers Reading Oscar Wilde to George Orwell Do we prefer satire or comedy? Do we take refuge in the serious or the frivolous? Do we understand the importance of being earnest or would we rather be in room 101? These two authors demonstrate well two powerful traditions in British literature, the comic and the satirical. They both of course share in each other’s art. Some would argue that during our present global crises we should look to Orwell more than ever, others would reach for the escapism of Oscar Wilde. In a new enterprise for the Cambridge Union, we are beginning our cultural debates – and this is our first. At least for a while.

Aging, Duration, and the English Novel argues that the formal disappearance of aging from the novel parallels the ideological pressure to identify as being young by repressing the process of growing old. The construction of aging as a shameful event that should be hidden – to improve one’s chances on the job market or secure a successful marriage – corresponds to the rise of the long novel, which draws upon the temporality of the body to map progress and decline onto the plots of nineteenth-century British modernity.

Aging, Duration, and the English Novel argues that the formal disappearance of aging from the novel parallels the ideological pressure to identify as being young by repressing the process of growing old. The construction of aging as a shameful event that should be hidden – to improve one’s chances on the job market or secure a successful marriage – corresponds to the rise of the long novel, which draws upon the temporality of the body to map progress and decline onto the plots of nineteenth-century British modernity.