From an Apollo Magazine online interview (Feb 22, 2020):

McCullin is reluctant to place himself in the company of artists, partly because he never wants to feel that he’s ‘arrived’ – ‘The moment that happens, I know I’m finished’ – but also because of the nature of his material. ‘There’s a shadow that  comes over my life when I think […] that I’ve earned my reputation out of other people’s downfall. I’ve photographed dead people and I’ve photographed dying people, and people looking at me who are about to be murdered in alleyways. So I carry the guilt of survival, the shame of not being able to help dying people.’

comes over my life when I think […] that I’ve earned my reputation out of other people’s downfall. I’ve photographed dead people and I’ve photographed dying people, and people looking at me who are about to be murdered in alleyways. So I carry the guilt of survival, the shame of not being able to help dying people.’

On top of a hill a few miles from Don McCullin’s house in Somerset is a dew pond, a perfectly circular artificial pond for watering livestock. Nobody knows how long it has been there; some dew ponds date back to prehistoric times, and it’s tempting to think that this one served the Bronze Age hill-fort that overlooks the site. McCullin is obsessed with the pond. For more than 30 years, whenever he has had the time, he has walked up the hill and stood there with his camera waiting for the right moment to take a photograph. Often, the moment never comes: he can spend hours there, just looking. ‘It’s as if it has a hold over me,’ he tells me when I visit him at home in early January. ‘I can’t leave it alone, I photograph it all the time. And yet I think I’ve done my best picture the first time I ever did it. I can’t tell you how.’

On top of a hill a few miles from Don McCullin’s house in Somerset is a dew pond, a perfectly circular artificial pond for watering livestock. Nobody knows how long it has been there; some dew ponds date back to prehistoric times, and it’s tempting to think that this one served the Bronze Age hill-fort that overlooks the site. McCullin is obsessed with the pond. For more than 30 years, whenever he has had the time, he has walked up the hill and stood there with his camera waiting for the right moment to take a photograph. Often, the moment never comes: he can spend hours there, just looking. ‘It’s as if it has a hold over me,’ he tells me when I visit him at home in early January. ‘I can’t leave it alone, I photograph it all the time. And yet I think I’ve done my best picture the first time I ever did it. I can’t tell you how.’

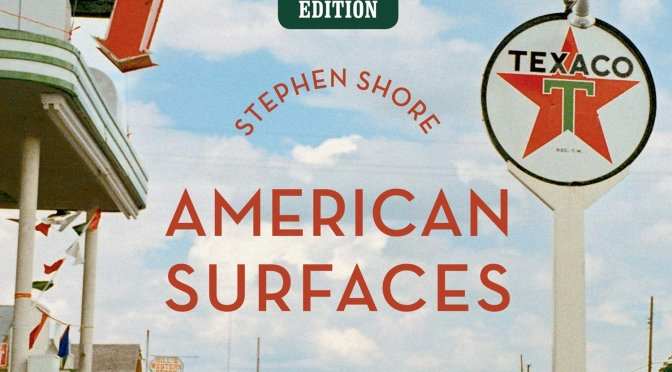

Stephen Shore’s images from his travels across America in 1972-73 are considered the benchmark for documenting the extraordinary in the ordinary and continue to influence photographers today.

Stephen Shore’s images from his travels across America in 1972-73 are considered the benchmark for documenting the extraordinary in the ordinary and continue to influence photographers today.

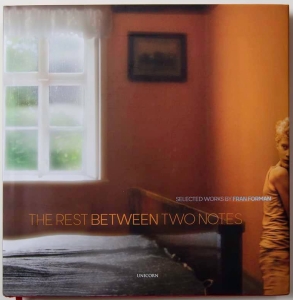

Forman’s photo-paintings explore those liminal and in-between moments – of coming and leaving, innocence and confidence, shadow and light, night and day, absence and connection, loss and longing, and not quite the past and not yet the future. Portals, both real and metaphorical, frequent her layered, complex and often dreamlike images.

Forman’s photo-paintings explore those liminal and in-between moments – of coming and leaving, innocence and confidence, shadow and light, night and day, absence and connection, loss and longing, and not quite the past and not yet the future. Portals, both real and metaphorical, frequent her layered, complex and often dreamlike images.

Her work is recognized for imbuing harmonious compositions and for her explosive use of color, light, and shadow.Forman’s images elicit emotions of desire, vulnerability, and a desperate longing for connections.

Her work is recognized for imbuing harmonious compositions and for her explosive use of color, light, and shadow.Forman’s images elicit emotions of desire, vulnerability, and a desperate longing for connections.

“Cherry Blossoms” reflects on the long tradition of flower viewing in Japanese culture with vivid color woodblock prints by ukiyo-e master artists, photographs, color lithographic posters and Kōkichi Tsunoi’s exquisite watercolor drawings from 1921. The book highlights the rich connections between Japan’s centuries-old traditions and contemporary counterparts. The American public’s affection for the blossoms is revealed in vintage and contemporary photographs of the Tidal Basin, collections related to the National Cherry Blossom Festival and the Cherry Blossom Princess Program, as well as decades’ worth of creatively designed festival posters.

“Cherry Blossoms” reflects on the long tradition of flower viewing in Japanese culture with vivid color woodblock prints by ukiyo-e master artists, photographs, color lithographic posters and Kōkichi Tsunoi’s exquisite watercolor drawings from 1921. The book highlights the rich connections between Japan’s centuries-old traditions and contemporary counterparts. The American public’s affection for the blossoms is revealed in vintage and contemporary photographs of the Tidal Basin, collections related to the National Cherry Blossom Festival and the Cherry Blossom Princess Program, as well as decades’ worth of creatively designed festival posters.

The vivid photographs are arranged according to the signs’ imagery, with sections such as Spirit of the West, On the Road, Now That’s Entertainment, and Ladies, Diving Girls & Mermaids. Sixteen of the most iconic landmark signs include brief histories on how that unique sign came to be. A resource section includes a photography index by location and a Neon Museums Visitor’s Guide.

The vivid photographs are arranged according to the signs’ imagery, with sections such as Spirit of the West, On the Road, Now That’s Entertainment, and Ladies, Diving Girls & Mermaids. Sixteen of the most iconic landmark signs include brief histories on how that unique sign came to be. A resource section includes a photography index by location and a Neon Museums Visitor’s Guide.

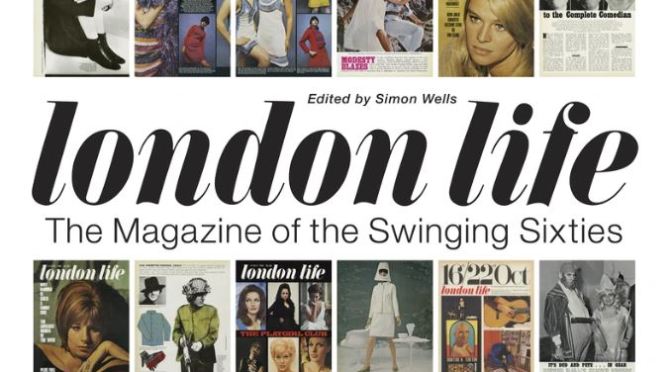

With imagery from the likes of David Bailey, Duffy and Terence Donovan, designs from Peter Blake, David Hockney, Gerald Scarfe and fledgling artist Ian Dury plus words and opinions from those riding high on the city`s cutting-edge, London Life remains the coolest document from the capital’s most exciting period.

With imagery from the likes of David Bailey, Duffy and Terence Donovan, designs from Peter Blake, David Hockney, Gerald Scarfe and fledgling artist Ian Dury plus words and opinions from those riding high on the city`s cutting-edge, London Life remains the coolest document from the capital’s most exciting period.

“Iceland’s glacial rivers are nature’s abstract paintings. It seems obvious that rivers this wild and stunning are protected, yet the harsh reality is that many have been dammed, mainly to provide power for aluminum plants.

“Iceland’s glacial rivers are nature’s abstract paintings. It seems obvious that rivers this wild and stunning are protected, yet the harsh reality is that many have been dammed, mainly to provide power for aluminum plants.