From a PLOS Biology Journal study (Feb 20, 2020):

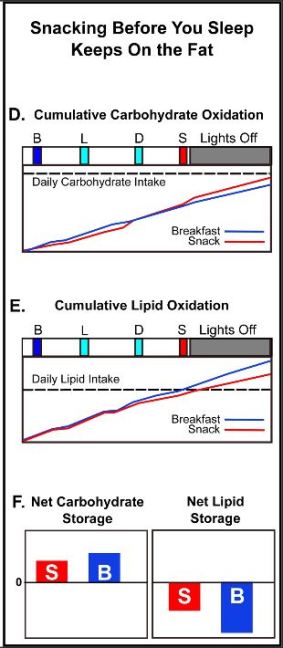

The major finding of this study is that the timing of feeding over the day leads to significant differences in the metabolism of an equivalent 24-h nutritional intake. Daily timing of nutrient availability coupled with daily/circadian control of metabolism drives a switch in substrate preference such that the late-evening Snack Session resulted in significantly lower LO compared to the Breakfast Session.

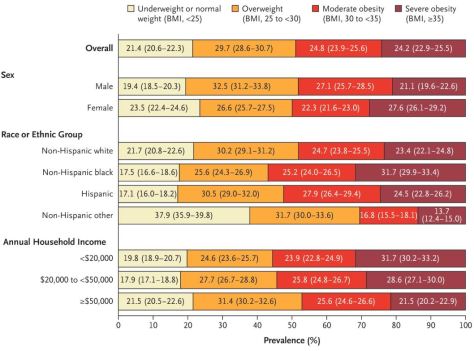

Developed countries are experiencing an epidemic of obesity that leads to many serious health problems, foremost among which are increasing rates of type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. While weight gain and obesity are primarily determined by diet and exercise, there is tremendous interest in the possibility that the daily timing of eating might have a significant impact upon weight management [1–3]. Many physiological processes display day/night rhythms, including feeding behavior, lipid and carbohydrate metabolism, body temperature, and sleep.

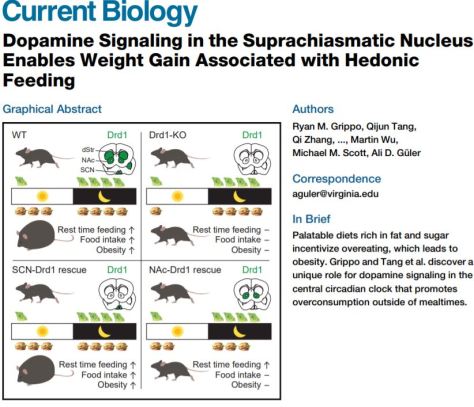

These daily oscillations are controlled by the circadian clock, which is composed of an autoregulatory biochemical mechanism that is expressed in tissues throughout the body and is coordinated by a master pacemaker located in the suprachiasmatic nuclei of the brain (aka the SCN [1,4]). The circadian system globally controls gene expression patterns so that metabolic pathways are differentially regulated over the day, including switching between carbohydrate and lipid catabolism [1,3,5–9]. Therefore, ingestion of the same food at different times of day could lead to differential metabolic outcomes, e.g., lipid oxidation (LO) versus accumulation; however, whether this is true or not is unclear.

These daily oscillations are controlled by the circadian clock, which is composed of an autoregulatory biochemical mechanism that is expressed in tissues throughout the body and is coordinated by a master pacemaker located in the suprachiasmatic nuclei of the brain (aka the SCN [1,4]). The circadian system globally controls gene expression patterns so that metabolic pathways are differentially regulated over the day, including switching between carbohydrate and lipid catabolism [1,3,5–9]. Therefore, ingestion of the same food at different times of day could lead to differential metabolic outcomes, e.g., lipid oxidation (LO) versus accumulation; however, whether this is true or not is unclear.

“Maintaining weight loss can get easier over time. Over time, less intentional effort, though not no effort, is needed to be successful. After about two years, healthy eating habits become part of the routine. Healthy choices become more automatic the longer people continue to make them. They feel weird when they don’t.”

“Maintaining weight loss can get easier over time. Over time, less intentional effort, though not no effort, is needed to be successful. After about two years, healthy eating habits become part of the routine. Healthy choices become more automatic the longer people continue to make them. They feel weird when they don’t.”

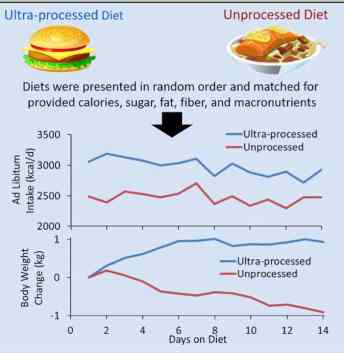

cookies and pies, salty snacks, frozen and shelf-stable dishes, pizza, and breakfast cereals.

cookies and pies, salty snacks, frozen and shelf-stable dishes, pizza, and breakfast cereals. Prevention

Prevention

This latest paper builds on previous Newcastle studies supported by

This latest paper builds on previous Newcastle studies supported by