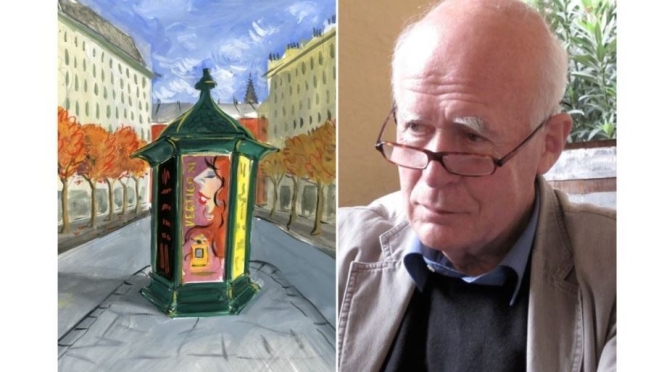

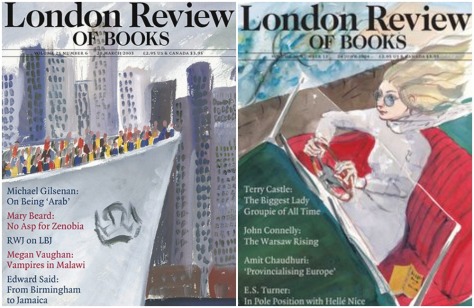

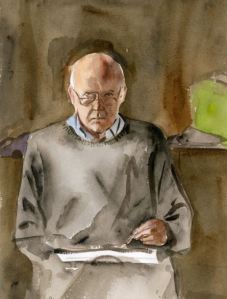

The website is about the work of the designer, writer and illustrator Peter Campbell (1937‑2011). The intention is to present an archive of Peter’s illustration, design and editorial work, as well as occasional selections from his writing.

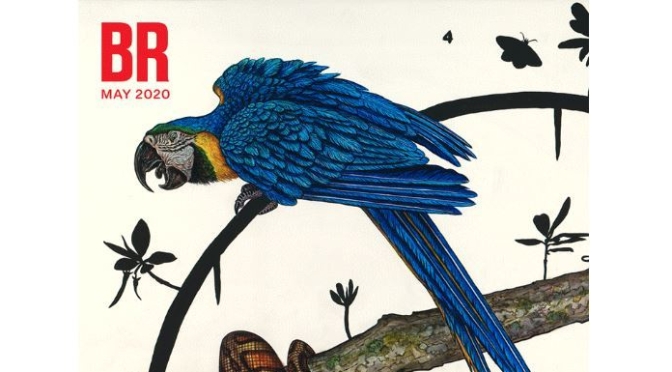

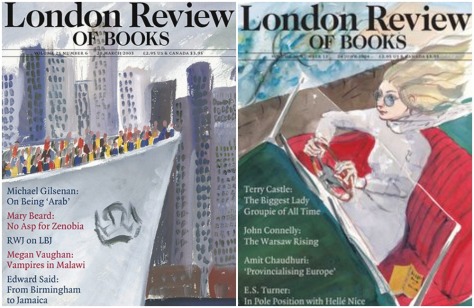

When asked what he did for a living, Peter would usually say he was a designer, or, a typographer. Designing for print – books, exhibition catalogues, magazines, posters –  took up the most substantial part of his time, at the BBC in the 1960s and 1970s and thereafter as a freelance. He was also an illustrator, a journalist, an author of children’s books, an editor and a publisher. The great range of his professional work, and his encompassing interest in the work of others, made him a collaborator sought out by writers, publishers and artists.

took up the most substantial part of his time, at the BBC in the 1960s and 1970s and thereafter as a freelance. He was also an illustrator, a journalist, an author of children’s books, an editor and a publisher. The great range of his professional work, and his encompassing interest in the work of others, made him a collaborator sought out by writers, publishers and artists.

Diana Souhami, who worked with Peter often, wrote in the Guardian after his death: “He had the ability to conceptualise what each publishing project needed and to get it right. He was hugely and diversely productive, but seldom hit a wrong note.”

Discussing his journalism in her appreciation in the London Review, Mary‑Kay Wilmers wrote: “There are people whom getting a grip doesn’t suit, who don’t want to be confined. One can honour the world in depth or across a wide range and there were few aspects of the world that Peter didn’t wish to honour.”

He probably would have been delighted by – and certainly modestly sceptical of – Alan Bennett’s appraisal, in the posthumous publication of a catalogue of his pictures in Artwork, that he was “an heir to Ardizzone, Bawden and Ravilious.”

Peter Campbell was born in Wellington, New Zealand in 1937. In 1960 he emigrated to London where he lived for the rest of his life. He died in 2011.

Website

In the latest episode in their series of Close Readings, Seamus Perry and Mark Ford look at the life and work of Robert Frost, the great American poet of fences and dark woods.

In the latest episode in their series of Close Readings, Seamus Perry and Mark Ford look at the life and work of Robert Frost, the great American poet of fences and dark woods.

By the time I used the camera lucida in the museum, I’d spent several months grappling with the strange proposition offered by its prism. I’d read that the image was sharper if you held it over a dark drawing surface, but that didn’t make any sense to me until the smoked metal etching plate was beneath my hand. Suddenly the albatross skeleton appeared on it: bright, spectral. The process was different from the way I’d imagined it. There was a drag, almost a dance, under the needle – a tiny jump of resistance in the copper. Without seeing what you were doing, you could feel it more keenly. It wasn’t like ice-skating at all.

By the time I used the camera lucida in the museum, I’d spent several months grappling with the strange proposition offered by its prism. I’d read that the image was sharper if you held it over a dark drawing surface, but that didn’t make any sense to me until the smoked metal etching plate was beneath my hand. Suddenly the albatross skeleton appeared on it: bright, spectral. The process was different from the way I’d imagined it. There was a drag, almost a dance, under the needle – a tiny jump of resistance in the copper. Without seeing what you were doing, you could feel it more keenly. It wasn’t like ice-skating at all. A camera lucida is an optical device used as a drawing aid by artists. The camera lucida performs an optical superimposition of the subject being viewed upon the surface upon which the artist is drawing. The artist sees both scene and drawing surface simultaneously, as in a photographic double exposure.

A camera lucida is an optical device used as a drawing aid by artists. The camera lucida performs an optical superimposition of the subject being viewed upon the surface upon which the artist is drawing. The artist sees both scene and drawing surface simultaneously, as in a photographic double exposure.

In his paintings we see books on their own, or books in the company of people or other objects; small, lonely ziggurats of books, or a book beside a candle. That last juxtaposition is telling in the extreme. Vincent had a reverence for books. They were sacred ground. They have a kind of inner glow about them.

In his paintings we see books on their own, or books in the company of people or other objects; small, lonely ziggurats of books, or a book beside a candle. That last juxtaposition is telling in the extreme. Vincent had a reverence for books. They were sacred ground. They have a kind of inner glow about them.

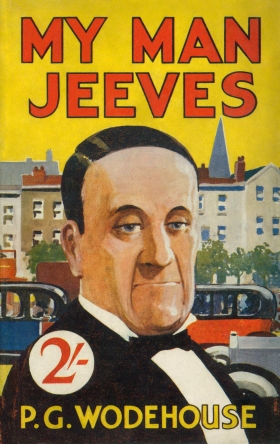

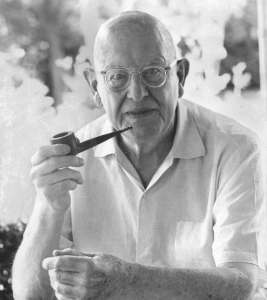

With every sparkling joke, every well-meaning and innocent character, every farcical tussle with angry swans and pet Pekingese, every utopian description of a stroll around the grounds of a pal’s stately home or a flutter on the choir boys’ hundred yards handicap at a summer village fete, he wanted to whisk us far away from our worries.

With every sparkling joke, every well-meaning and innocent character, every farcical tussle with angry swans and pet Pekingese, every utopian description of a stroll around the grounds of a pal’s stately home or a flutter on the choir boys’ hundred yards handicap at a summer village fete, he wanted to whisk us far away from our worries. T

T

Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein

took up the most substantial part of his time, at the BBC in the 1960s and 1970s and thereafter as a freelance. He was also an illustrator, a journalist, an author of children’s books, an editor and a publisher. The great range of his professional work, and his encompassing interest in the work of others, made him a collaborator sought out by writers, publishers and artists.

took up the most substantial part of his time, at the BBC in the 1960s and 1970s and thereafter as a freelance. He was also an illustrator, a journalist, an author of children’s books, an editor and a publisher. The great range of his professional work, and his encompassing interest in the work of others, made him a collaborator sought out by writers, publishers and artists.