From a Christie’s online article:

Shortly after George Orwell’s death in 1950, his widow Sonia was visited in London by two representatives of the American film producer, Louis de Rochemont. They sought the rights to Orwell’s novel from five years earlier, Animal Farm. It’s said Sonia took some convincing but eventually agreed, on the promise that de Rochemont would introduce her to her hero, Clark Gable.

Shortly after George Orwell’s death in 1950, his widow Sonia was visited in London by two representatives of the American film producer, Louis de Rochemont. They sought the rights to Orwell’s novel from five years earlier, Animal Farm. It’s said Sonia took some convincing but eventually agreed, on the promise that de Rochemont would introduce her to her hero, Clark Gable.

A conventional, live-action adaptation was out of the question given that the book’s main characters were farmyard animals, so an animated movie was decided upon instead. De Rochemont chose to have it made in the UK rather than the US — partly because of lower production costs, partly because he admired the work of British husband-and-wife duo John Halas and Joy Batchelor, a couple who ran their own animation studio and had produced several propaganda films for the British government during the Second World War.

A conventional, live-action adaptation was out of the question given that the book’s main characters were farmyard animals, so an animated movie was decided upon instead. De Rochemont chose to have it made in the UK rather than the US — partly because of lower production costs, partly because he admired the work of British husband-and-wife duo John Halas and Joy Batchelor, a couple who ran their own animation studio and had produced several propaganda films for the British government during the Second World War.

Their adaptation of Animal Farm was released in 1954, to popular and critical acclaim — the first feature-length animation movie ever made in the UK.

A key writer of the late 19th century, Joris-Karl Huysmans (1848-1907) was an art critic who is still little known or little understood by the general public. However, his contribution to the artistic press and the aesthetic debate was as decisive as the impact of his novel

A key writer of the late 19th century, Joris-Karl Huysmans (1848-1907) was an art critic who is still little known or little understood by the general public. However, his contribution to the artistic press and the aesthetic debate was as decisive as the impact of his novel  More passionate about Hals and Rembrandt until his discovery of Degas in 1876-1879, Huysmans admitted that this was a defining moment. And yet, his art criticism immediately accepted the possibility of a double modernity. The modernity of the painters of modern life and that of the explorers of dreams were not mutually exclusive. Here, Manet coexists with Rops and Redon. The desire Huysmans showed very early on to escape from the logic of church doctrine no doubt blurred the perception of his aesthetic choices.

More passionate about Hals and Rembrandt until his discovery of Degas in 1876-1879, Huysmans admitted that this was a defining moment. And yet, his art criticism immediately accepted the possibility of a double modernity. The modernity of the painters of modern life and that of the explorers of dreams were not mutually exclusive. Here, Manet coexists with Rops and Redon. The desire Huysmans showed very early on to escape from the logic of church doctrine no doubt blurred the perception of his aesthetic choices.

I chose to call myself a portrait photographer because labels were always being thrown on me. When I was at Rolling Stone I was a ‘rock-and-roll photographer’, at Vanity Fair I was a ‘celebrity photographer’. You know, I’m just a photographer. I realised I wasn’t really a journalist. I have a point of view and, while these photographs that I call portraits can be conceptual or illustrative, that keeps me on the straight and narrow. So I settled on this brand called ‘portraits’ because it had a lot of leeway. But I don’t think of myself that way now: I think of myself as a conceptual artist using photography.

I chose to call myself a portrait photographer because labels were always being thrown on me. When I was at Rolling Stone I was a ‘rock-and-roll photographer’, at Vanity Fair I was a ‘celebrity photographer’. You know, I’m just a photographer. I realised I wasn’t really a journalist. I have a point of view and, while these photographs that I call portraits can be conceptual or illustrative, that keeps me on the straight and narrow. So I settled on this brand called ‘portraits’ because it had a lot of leeway. But I don’t think of myself that way now: I think of myself as a conceptual artist using photography. I remember going to the Factory in 1976 and watching Andy Warhol work. I’d been there before, earlier in the 70s, photographing Joe Dallesandro and Holly Woodlawn, and then Paul Morrissey. Warhol was a fixture of New York. It was just shocking when he died, because he was everywhere. I don’t know how he did it, but he was out at everything. You felt that if he was at a place you were at, then you were at the right place.

I remember going to the Factory in 1976 and watching Andy Warhol work. I’d been there before, earlier in the 70s, photographing Joe Dallesandro and Holly Woodlawn, and then Paul Morrissey. Warhol was a fixture of New York. It was just shocking when he died, because he was everywhere. I don’t know how he did it, but he was out at everything. You felt that if he was at a place you were at, then you were at the right place.

One of the most successful artists of the Italian Renaissance, Titian was the master of the sixteenth-century Venetian school and admired by his royal patrons and fellow artists alike. Several of his contemporaries, including the authors and art theorists Giorgio Vasari, Francesco Priscianese, Pietro Aretino, and Ludovico Dolce, wrote accounts of Titian’s life and work.

One of the most successful artists of the Italian Renaissance, Titian was the master of the sixteenth-century Venetian school and admired by his royal patrons and fellow artists alike. Several of his contemporaries, including the authors and art theorists Giorgio Vasari, Francesco Priscianese, Pietro Aretino, and Ludovico Dolce, wrote accounts of Titian’s life and work. In this episode, Getty assistant curator of paintings Laura Llewellyn discusses what these “lives” teach us about Titian and the artistic debates and rivalries of his time. All of these biographies are gathered together in Lives of Titian, recently published by the Getty as part of our Lives of the Artists series.

In this episode, Getty assistant curator of paintings Laura Llewellyn discusses what these “lives” teach us about Titian and the artistic debates and rivalries of his time. All of these biographies are gathered together in Lives of Titian, recently published by the Getty as part of our Lives of the Artists series.

The Credit Suisse Exhibition: Gauguin Portraits 7 October 2019 – 26 January 2020 Book tickets online and save, Members go free:

The Credit Suisse Exhibition: Gauguin Portraits 7 October 2019 – 26 January 2020 Book tickets online and save, Members go free:

How is a drapery put in place? For what reasons does this motive persist until today? How to explain its power of fascination? These are the questions that this exhibition intends to pose, in order to enter the “factory” of the drapery and to get closer to the artistic gesture. By showing the stages of making a drapery, the visitor will discover the singular practices of artists from the Renaissance to the second half of the 20th century.

How is a drapery put in place? For what reasons does this motive persist until today? How to explain its power of fascination? These are the questions that this exhibition intends to pose, in order to enter the “factory” of the drapery and to get closer to the artistic gesture. By showing the stages of making a drapery, the visitor will discover the singular practices of artists from the Renaissance to the second half of the 20th century. Albrecht Dürer, Drapery Study, 1508, Brush and Indian Ink, heightened white on dark green paper

Albrecht Dürer, Drapery Study, 1508, Brush and Indian Ink, heightened white on dark green paper

“Everywhere is the wait and the gathering,” concludes “Resort.” A kind of soporific haze has seeped into de Chirico’s imagination, asserted through evocations of sleeping and dreaming. Even the violence and ambiguous sexual imagery of “The Mysterious Night” yield to a final note of definitive somnolence: “Everything sleeps; even the owls and the bats who also in the dream dream of sleeping.”

“Everywhere is the wait and the gathering,” concludes “Resort.” A kind of soporific haze has seeped into de Chirico’s imagination, asserted through evocations of sleeping and dreaming. Even the violence and ambiguous sexual imagery of “The Mysterious Night” yield to a final note of definitive somnolence: “Everything sleeps; even the owls and the bats who also in the dream dream of sleeping.” He daydreams of Mexico or Alaska and invokes a future-oriented “avant-city” and a distant day where he is immortalized, albeit in an old-fashioned mode as a “man of marble.”

He daydreams of Mexico or Alaska and invokes a future-oriented “avant-city” and a distant day where he is immortalized, albeit in an old-fashioned mode as a “man of marble.”

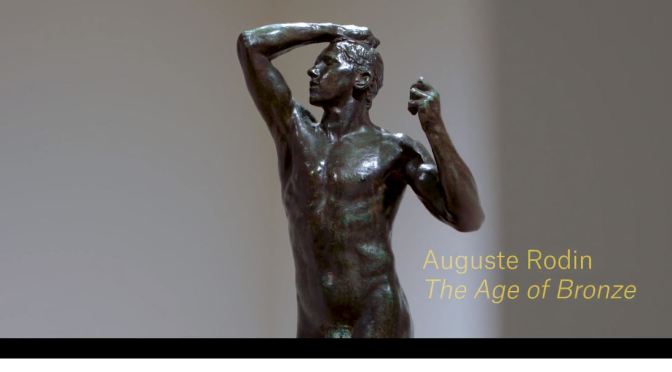

Rodin first exhibited a bronze and a plaster version of

Rodin first exhibited a bronze and a plaster version of