From a Harvard Gazette online article:

The Grand Challenge Prize is looking for bold, audacious innovations, ideas that can really change aging. We’re looking in science, in technology and engineering, in policy, social sciences, behavioral sciences, economic policy, in traditional medical science and health care, and in work focused on specific diseases. It’s really very broad. We’re looking for innovative thinking that can have global impact. The prizes are going to roll out on three levels. There will be 450 Catalyst Prizes awarded over a three-year period. The first of the three yearly calls will be in January 2020. Once it’s announced, there will be six weeks to submit your idea — just the idea, it doesn’t require any pilot work — and a two-page application. They’ll be reviewed within four months and prizes announced by July. The Catalyst Award is intended as seed funding to get the idea into its earliest stages of development. They’re relatively small in dollar amount, about $50,000 each, but they will give access to an annual meeting bringing together world experts in these fields.

The Grand Challenge Prize is looking for bold, audacious innovations, ideas that can really change aging. We’re looking in science, in technology and engineering, in policy, social sciences, behavioral sciences, economic policy, in traditional medical science and health care, and in work focused on specific diseases. It’s really very broad. We’re looking for innovative thinking that can have global impact. The prizes are going to roll out on three levels. There will be 450 Catalyst Prizes awarded over a three-year period. The first of the three yearly calls will be in January 2020. Once it’s announced, there will be six weeks to submit your idea — just the idea, it doesn’t require any pilot work — and a two-page application. They’ll be reviewed within four months and prizes announced by July. The Catalyst Award is intended as seed funding to get the idea into its earliest stages of development. They’re relatively small in dollar amount, about $50,000 each, but they will give access to an annual meeting bringing together world experts in these fields.

The world’s aging population means there will be an increasing number of older and sicker people at a time when declining fertility will saddle a smaller working population with the burden of supporting them. One solution is to keep people healthier longer, living independently, and contributing to society. In pursuit of that goal, the National Academy of Medicine is mounting a $30 million Grand Challenge contest to foster innovation in science, medicine, public policy, the workplace, and elsewhere. Sharon Inouye, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and head of the Aging Brain Center at Harvard-affiliated Hebrew Senior Life, is a National Academy member and a member of the planning committee for the Grand Challenge for Healthy Longevity. She spoke to the Gazette about the contest and how she hopes it changes the nature of aging in the decades to come.

To read more: https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2019/11/grand-challenge-encourages-innovation-in-aging/

Researchers matched 7,743 people with osteoarthritis with 23,229 healthy people who rarely or never took NSAIDs. People with osteoarthritis had a 42% higher risk of heart failure and a 17% higher risk of coronary artery disease compared with healthy people. After controlling for a range of factors that contribute to heart disease (including high body mass index, high blood pressure, and diabetes), they concluded that 41% of the increased risk of heart disease related to osteoarthritis was due to the use of NSAIDs.

Researchers matched 7,743 people with osteoarthritis with 23,229 healthy people who rarely or never took NSAIDs. People with osteoarthritis had a 42% higher risk of heart failure and a 17% higher risk of coronary artery disease compared with healthy people. After controlling for a range of factors that contribute to heart disease (including high body mass index, high blood pressure, and diabetes), they concluded that 41% of the increased risk of heart disease related to osteoarthritis was due to the use of NSAIDs.

“When you live paycheck to paycheck, there are times you fall behind. There was a healthy dose of fear, but I knew that my business would grow if I kept pushing.” Getting an M.B.A. felt superfluous. “I would rather be paid to learn,” he said. “There’s not a lot you can learn in an M.B.A. program that you can’t learn online or through other mechanisms. I’m not a big fan of taking those years and spending money that you could put to better use.”

“When you live paycheck to paycheck, there are times you fall behind. There was a healthy dose of fear, but I knew that my business would grow if I kept pushing.” Getting an M.B.A. felt superfluous. “I would rather be paid to learn,” he said. “There’s not a lot you can learn in an M.B.A. program that you can’t learn online or through other mechanisms. I’m not a big fan of taking those years and spending money that you could put to better use.”

“This study identifies a new molecular connection between exercise and inflammation that takes place in the bone marrow and highlights a previously unappreciated role of leptin in exercise-mediated cardiovascular protection,” said Michelle Olive, program officer at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Division of Cardiovascular Sciences. “This work adds a new piece to the puzzle of how sedentary lifestyles affect cardiovascular health and underscores the importance of following physical-activity guidelines.”

“This study identifies a new molecular connection between exercise and inflammation that takes place in the bone marrow and highlights a previously unappreciated role of leptin in exercise-mediated cardiovascular protection,” said Michelle Olive, program officer at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Division of Cardiovascular Sciences. “This work adds a new piece to the puzzle of how sedentary lifestyles affect cardiovascular health and underscores the importance of following physical-activity guidelines.”

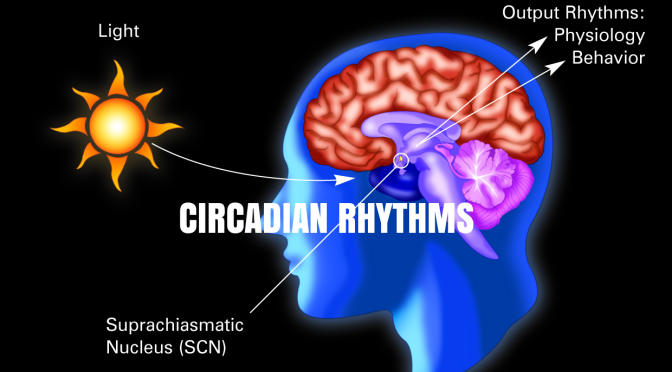

When people are awake during the night, their behaviors are often mismatched with their internal body clocks. This can lead to nighttime eating, which can influence the way the body processes sugar and could lead to a higher risk in diabetes. “What happens when food is eaten when you normally should be fasting?” Scheer asked the audience. “What happens is that your glucose tolerance goes out the window….So your glucose levels after a meal are much higher.” This can increase people’s risk for diabetes.

When people are awake during the night, their behaviors are often mismatched with their internal body clocks. This can lead to nighttime eating, which can influence the way the body processes sugar and could lead to a higher risk in diabetes. “What happens when food is eaten when you normally should be fasting?” Scheer asked the audience. “What happens is that your glucose tolerance goes out the window….So your glucose levels after a meal are much higher.” This can increase people’s risk for diabetes.

Six factors measured by age 50 were excellent predictors of those who would be in the “happy-well” group–the top quartile of the Harvard men–at age 80: a stable marriage, a mature adaptive style, no smoking, little use of alcohol, regular exercise, and maintenance of normal weight. At age 50, 106 of the men had five or six of these factors going for them, and at 80, half of this group were among the happy-well. Only eight fell into the “sad-sick” category, the bottom quarter of life outcomes. In contrast, of 66 men who had only one to three factors at age 50, not a single one was rated happy-well at 80. In addition, men with three or fewer factors, though still in good physical health at 50, were three times as likely to be dead 30 years later as those with four or more.

Six factors measured by age 50 were excellent predictors of those who would be in the “happy-well” group–the top quartile of the Harvard men–at age 80: a stable marriage, a mature adaptive style, no smoking, little use of alcohol, regular exercise, and maintenance of normal weight. At age 50, 106 of the men had five or six of these factors going for them, and at 80, half of this group were among the happy-well. Only eight fell into the “sad-sick” category, the bottom quarter of life outcomes. In contrast, of 66 men who had only one to three factors at age 50, not a single one was rated happy-well at 80. In addition, men with three or fewer factors, though still in good physical health at 50, were three times as likely to be dead 30 years later as those with four or more.