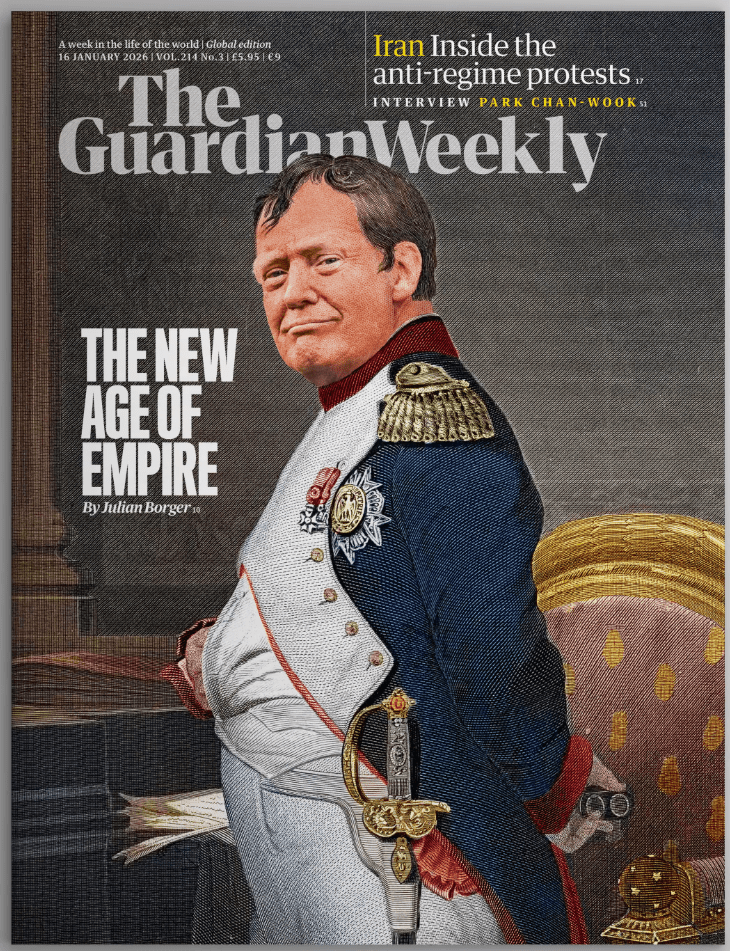

THE GUARDIAN WEEKLY: The latest issue features ‘USA-IRAN’ – Collision Course….

Have Donald Trump’s hard talk and the arrival of a strike-ready flotilla finally made Tehran blink? It certainly seemed so by Monday evening, when Iran said it was willing to talk. A week of trading threats turned to strong indications that Steve Witkoff, Trump’s envoy, and Abbas Araghchi, Iran’s minister for foreign affairs, were readying to meet in Istanbul on Friday. In this week’s big story, Ashifa Kassam and Andrew Roth chart how momentum to war slowed and fears of a wider regional conflict eased, albeit marginally.

The background to Trump’s war of words against Tehran was the huge protests that rocked Iran last month, until they were brutally repressed by the regime. Analysts suggest a fragile domestic security situation prompted the Iranian government’s softening towards US demands. Our diplomatic editor and longtime Iran watcher, Patrick Wintour, explains that while the streets are now quiet, a shift in the balance of power between the people and the government has emboldened domestic demands for a full investigation of the killing and imprisonment of protesters.

Spotlight | The Epstein files, part two

Daniel Boffey details the biggest bombshell among the 3m newly released documents: disgraced former minister Peter Mandelson’s deep and compromising relationship with the convicted paedophile

Environment | Nature runs wild in Fukushima

Free of human habitation after the 2011 earthquake, tsunami and nuclear meltdown, Fukushima is now teeming with wildlife. But this haven could vanish if people come back, finds Justin McCurry

Features | From hope to despair

The postwar new town of Newton Aycliffe with its boarded up shops is a symbol of the Britain’s economic gloom – and a warning for Labour as it battles the rise of Reform UK, reports Josh Halliday

Opinion | Art, groceries, Greenland – thieves are everywhere

Jonathan Liew reflects on how we all seem to live in a world defined by petty theft and no one, whether it’s the pickpocket or the big AI company, seems to get punished

Culture | Small acts of magic

Mackenzie Crook tells Zoe Williams how his approach to comedy has mellowed with age. Gone is the nervous, awkward energy of Gareth from The Office, to be replaced by the gentle curiosity that animates his new series Small Prophets