From The Mayfair Musings:

I describe myself as an urban-based painter who is interested in green spaces. Painting and drawing have been seen as profoundly unfashionable for most of my working life, and I have felt sometimes that it was quite eccentric to be a figurative painter with conventional subject matter. Looking back, my insistence on maintaining my practice as a figurative painter now seems more radical than conventional.

I describe myself as an urban-based painter who is interested in green spaces. Painting and drawing have been seen as profoundly unfashionable for most of my working life, and I have felt sometimes that it was quite eccentric to be a figurative painter with conventional subject matter. Looking back, my insistence on maintaining my practice as a figurative painter now seems more radical than conventional.

Browse & Darby have announced that Personal Geographies will arrive in October, the second solo exhibition by esteemed British painter, Eileen Hogan. Hogan’s principal subject is gardens, or more specifically, enclosed green spaces. The beautiful works that will be shown in Personal Geographies have travelled all the way from the US, where they formed part of the artist’s recent exhibition at the Yale Centre for British Art.

I was very blessed to have the opportunity to catch up with Hogan ahead of her Mayfair exhibition. I find myself entranced by her vibrant paintings that are dense with detail, filling the canvas from edge to edge with layers upon layers of paint. She has also established portraiture practice, her commissions including HRH The Prince of Wales. In a unique style, Hogan paints her sitters whilst they are deep in conversation, capturing unguarded gestures and expressions to create intricate portraits of both honesty and intimacy.

I was very blessed to have the opportunity to catch up with Hogan ahead of her Mayfair exhibition. I find myself entranced by her vibrant paintings that are dense with detail, filling the canvas from edge to edge with layers upon layers of paint. She has also established portraiture practice, her commissions including HRH The Prince of Wales. In a unique style, Hogan paints her sitters whilst they are deep in conversation, capturing unguarded gestures and expressions to create intricate portraits of both honesty and intimacy.

To read more: https://www.themayfairmusings.com/home/10-questions-with-eileen-hogan

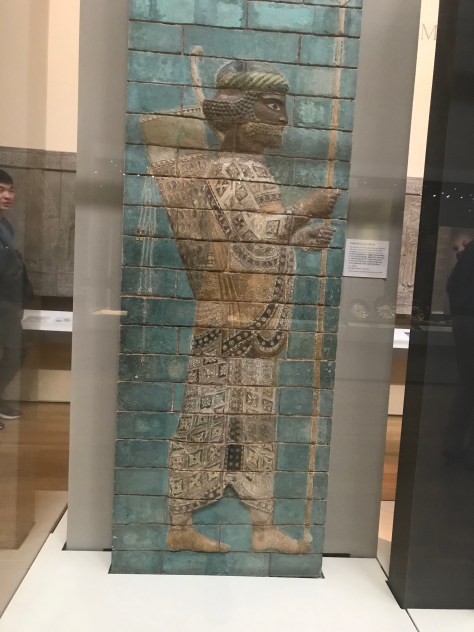

Things take an even stranger turn when he gets to Egypt, and his own features still appear again and again; not, as before, as a barely significant detail in an otherwise busy composition, but as a principal element. In a series of fine single-figure paintings brought together at the Watts Gallery, Lewis represents himself as a Syrian sheikh scanning the horizon of the Sinai desert; as the suave ‘bey’ of a Cairene household, lowering his eyelids as his servant offers him a water pipe; as an impassive carpet-seller in the Bezestein bazaar

Things take an even stranger turn when he gets to Egypt, and his own features still appear again and again; not, as before, as a barely significant detail in an otherwise busy composition, but as a principal element. In a series of fine single-figure paintings brought together at the Watts Gallery, Lewis represents himself as a Syrian sheikh scanning the horizon of the Sinai desert; as the suave ‘bey’ of a Cairene household, lowering his eyelids as his servant offers him a water pipe; as an impassive carpet-seller in the Bezestein bazaar

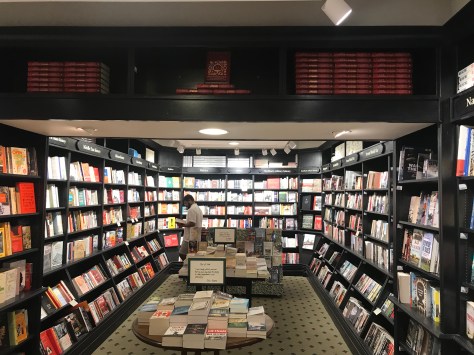

After a great British breakfast, hopped on the Tube at Tower Hill and headed for the South Kensington station. Arrived at the Victoria & Albert Museum as it opened at 10.

After a great British breakfast, hopped on the Tube at Tower Hill and headed for the South Kensington station. Arrived at the Victoria & Albert Museum as it opened at 10.

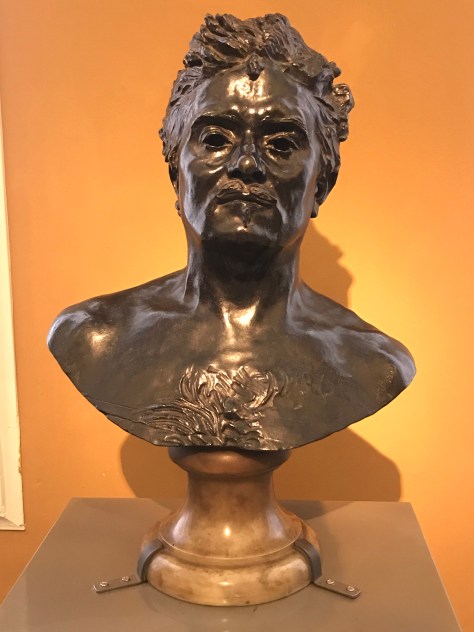

Édouard Manet was a provocateur and a dandy, the Impressionist generation’s great painter of modern Paris. This first-ever exhibition to explore the last years of Manet’s short life and career reveals a fresh and surprisingly intimate aspect of this celebrated artist’s work. Stylish portraits,

Édouard Manet was a provocateur and a dandy, the Impressionist generation’s great painter of modern Paris. This first-ever exhibition to explore the last years of Manet’s short life and career reveals a fresh and surprisingly intimate aspect of this celebrated artist’s work. Stylish portraits,  luscious still lifes, delicate pastels and watercolors, and vivid café and garden scenes convey Manet’s elegant social world and reveal his growing fascination with fashion, flowers, and his view of the parisienne—a feminine embodiment of modern life in all its particular, fleeting beauty.

luscious still lifes, delicate pastels and watercolors, and vivid café and garden scenes convey Manet’s elegant social world and reveal his growing fascination with fashion, flowers, and his view of the parisienne—a feminine embodiment of modern life in all its particular, fleeting beauty.

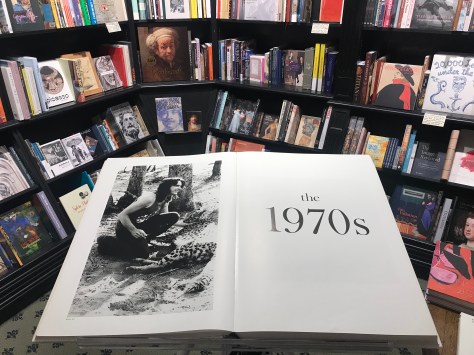

Rigorously unsentimental in his attitude to the world around him, Mr. Frank deviated from form in 1950, taking what was arguably his most romantic picture. He had his reasons. He was in love. The year before he had met artist Mary Lockspeiser, who became his first wife. In “Tulip/Paris,” he photographed a young man who is holding behind his back a tulip — presumably intended for the woman standing in the background. An old man, at the other end of life’s arc, approaches the viewer. It is a classic romantic Paris street photograph.

Rigorously unsentimental in his attitude to the world around him, Mr. Frank deviated from form in 1950, taking what was arguably his most romantic picture. He had his reasons. He was in love. The year before he had met artist Mary Lockspeiser, who became his first wife. In “Tulip/Paris,” he photographed a young man who is holding behind his back a tulip — presumably intended for the woman standing in the background. An old man, at the other end of life’s arc, approaches the viewer. It is a classic romantic Paris street photograph.

Though his paintings and sculptures sell all over the world for fabulous prices, he has not enriched himself. He lives simply, with his wife, Trine Ellitsgaard Lopez, an accomplished weaver, in a traditional house in the middle of Oaxaca, and has used his considerable profits to found art centers and museums, an ethnobotanical garden and at least three libraries.

Though his paintings and sculptures sell all over the world for fabulous prices, he has not enriched himself. He lives simply, with his wife, Trine Ellitsgaard Lopez, an accomplished weaver, in a traditional house in the middle of Oaxaca, and has used his considerable profits to found art centers and museums, an ethnobotanical garden and at least three libraries. Toledo, whose origins were obscure and inauspicious, was the son of a leatherworker—shoemaker and tanner. He was born in Mexico City, but the family soon after moved to their ancestral village near Juchitán de Zaragoza in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, nearer to Guatemala than to Mexico City—and being ethnically Zapotec, nearer culturally to the ancient pieties of the hinterland too.

Toledo, whose origins were obscure and inauspicious, was the son of a leatherworker—shoemaker and tanner. He was born in Mexico City, but the family soon after moved to their ancestral village near Juchitán de Zaragoza in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, nearer to Guatemala than to Mexico City—and being ethnically Zapotec, nearer culturally to the ancient pieties of the hinterland too.

That’s the kind of astonishing illumination you’ll find in The Trojan War Museum, Ayşe Papatya Bucak’s debut story collection. These are stories that reflect the author’s Turkish heritage and a curiosity about our human search for meaning as profound as it is lyrical. The stories are music. They beguile and illuminate with narratives about yearning and desire, circumstance and courage, resilience and discovery. Reading them, while the reading lasts, replaces seeing.

That’s the kind of astonishing illumination you’ll find in The Trojan War Museum, Ayşe Papatya Bucak’s debut story collection. These are stories that reflect the author’s Turkish heritage and a curiosity about our human search for meaning as profound as it is lyrical. The stories are music. They beguile and illuminate with narratives about yearning and desire, circumstance and courage, resilience and discovery. Reading them, while the reading lasts, replaces seeing.

The Glass House, designed by architect Philip Johnson in 1949, when floor-to-ceiling windows were a novelty even in office buildings, is a work of art in itself. But there’s much more art to be found on the lush grounds of this famous home in New Canaan, Connecticut. Amble on over to the Painting Gallery, which houses large-scale works by Frank Stella, Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, and Cindy Sherman, among others, or the Sculpture Gallery, featuring works by such artists as Michael Heizer, George Segal, Frank Stella, and Bruce Nauman.

The Glass House, designed by architect Philip Johnson in 1949, when floor-to-ceiling windows were a novelty even in office buildings, is a work of art in itself. But there’s much more art to be found on the lush grounds of this famous home in New Canaan, Connecticut. Amble on over to the Painting Gallery, which houses large-scale works by Frank Stella, Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, and Cindy Sherman, among others, or the Sculpture Gallery, featuring works by such artists as Michael Heizer, George Segal, Frank Stella, and Bruce Nauman.

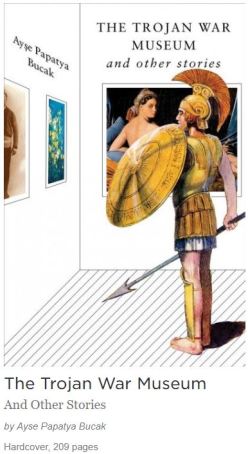

The 200 pages on display at the Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, have been together since the artist’s death. They were bound by the sculptor Pompeo Leoni in about 1590 and entered the Royal Collection during the reign of Charles II. Some of his most iconic images are here, including his study of a foetus in the womb, made as part of a treatise on anatomy that came close to being finished, but was never published.

The 200 pages on display at the Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, have been together since the artist’s death. They were bound by the sculptor Pompeo Leoni in about 1590 and entered the Royal Collection during the reign of Charles II. Some of his most iconic images are here, including his study of a foetus in the womb, made as part of a treatise on anatomy that came close to being finished, but was never published.

Pencils are discarded, as lighters and umbrellas are, because at some crucial moment they fail in their purpose. They refuse to ignite, quail before a shower, or simply snap. But pencils have merely suspended their usefulness. Their potential still lies within them. They can go on setting down by the thousand the words by which the world works.

Pencils are discarded, as lighters and umbrellas are, because at some crucial moment they fail in their purpose. They refuse to ignite, quail before a shower, or simply snap. But pencils have merely suspended their usefulness. Their potential still lies within them. They can go on setting down by the thousand the words by which the world works.