Michelangelo is among the most influential and impressive artists of the Italian High Renaissance. His lifelike sculptures and powerful paintings are some of the most recognizable works in Western art history. He also drew prolifically, making sketch after sketch of figures in slightly varying poses, focusing on form and gesture.

However, remarkably few of these drawings remain today, many of them burned by the artist himself, others lost or damaged over the centuries.

A recent exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Michelangelo: Mind of the Master, brought together more than two dozen of Michelangelo’s surviving drawings—including designs for the Sistine Chapel ceiling and The Last Judgment—to shed light on the artist’s creativity and working method. In this episode, co-curators of this exhibition, Julian Brooks and Edina Adam, discuss the master and what we can learn from his works on paper.

For images, transcripts, and more, visit getty.edu/podcasts.

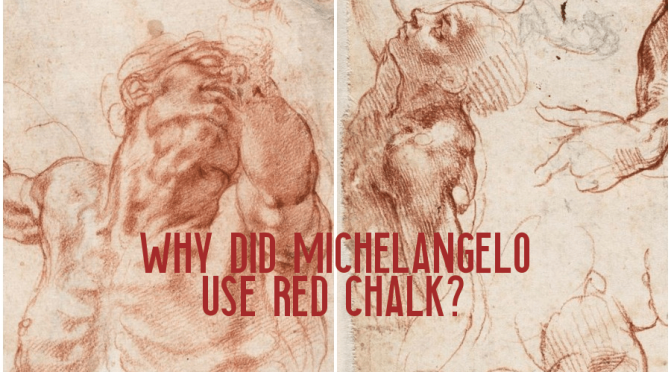

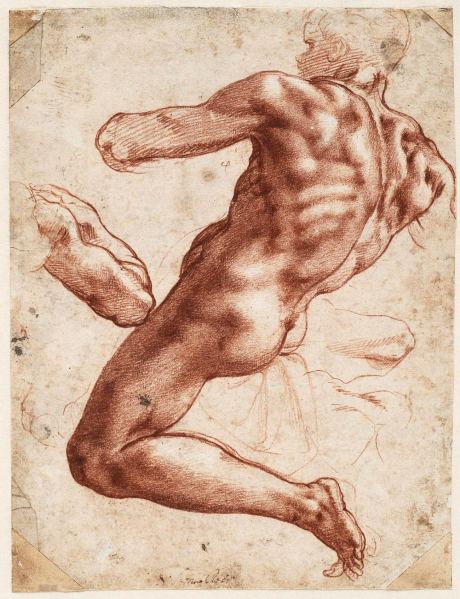

To work out the details of all the figures in pen and ink would have been extremely labor-intensive, and sharpening quills and mixing inks would’ve added an additional distraction. Drawing in chalk necessitated great skill, but it also allowed Michelangelo a flexibility. He could create subtle tonal variations by applying more or less pressure onto the chalk or by wetting it. The red chalk also provided an immediate mid-tone on the paper and could be easily blended when modeling and shading forms. Being a naturally occurring material that was available to artists in sticks that could be sharpened as desired, it was also convenient and portable.

To work out the details of all the figures in pen and ink would have been extremely labor-intensive, and sharpening quills and mixing inks would’ve added an additional distraction. Drawing in chalk necessitated great skill, but it also allowed Michelangelo a flexibility. He could create subtle tonal variations by applying more or less pressure onto the chalk or by wetting it. The red chalk also provided an immediate mid-tone on the paper and could be easily blended when modeling and shading forms. Being a naturally occurring material that was available to artists in sticks that could be sharpened as desired, it was also convenient and portable. During his lifetime, Michelangelo likely produced tens of thousands of drawings. But being protective of his ideas, and to give an impression of effortless genius, he destroyed many of them. Today only about 600 drawings by the Renaissance artist survive.

During his lifetime, Michelangelo likely produced tens of thousands of drawings. But being protective of his ideas, and to give an impression of effortless genius, he destroyed many of them. Today only about 600 drawings by the Renaissance artist survive.

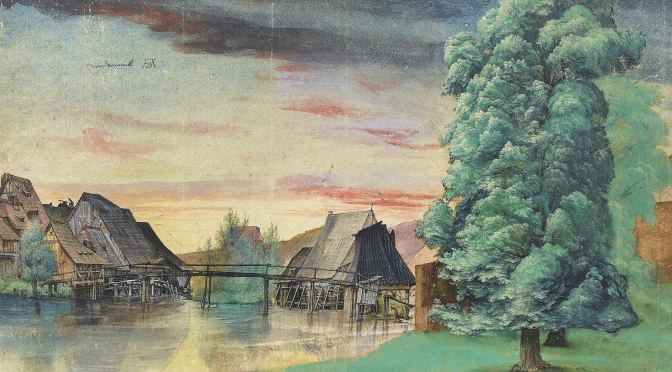

This book showcases more than 100 of Dürer’s drawings including Hare, Self Portrait at the Age of 13, and Melencolia I, along with paintings and prints. Featuring scholarly essays and beautifully reproduced works, this book shows the reader not only how important Dürer’s drawings are to his own oeuvre, but also how he helped drawing become an appreciated medium in its own right.

This book showcases more than 100 of Dürer’s drawings including Hare, Self Portrait at the Age of 13, and Melencolia I, along with paintings and prints. Featuring scholarly essays and beautifully reproduced works, this book shows the reader not only how important Dürer’s drawings are to his own oeuvre, but also how he helped drawing become an appreciated medium in its own right.

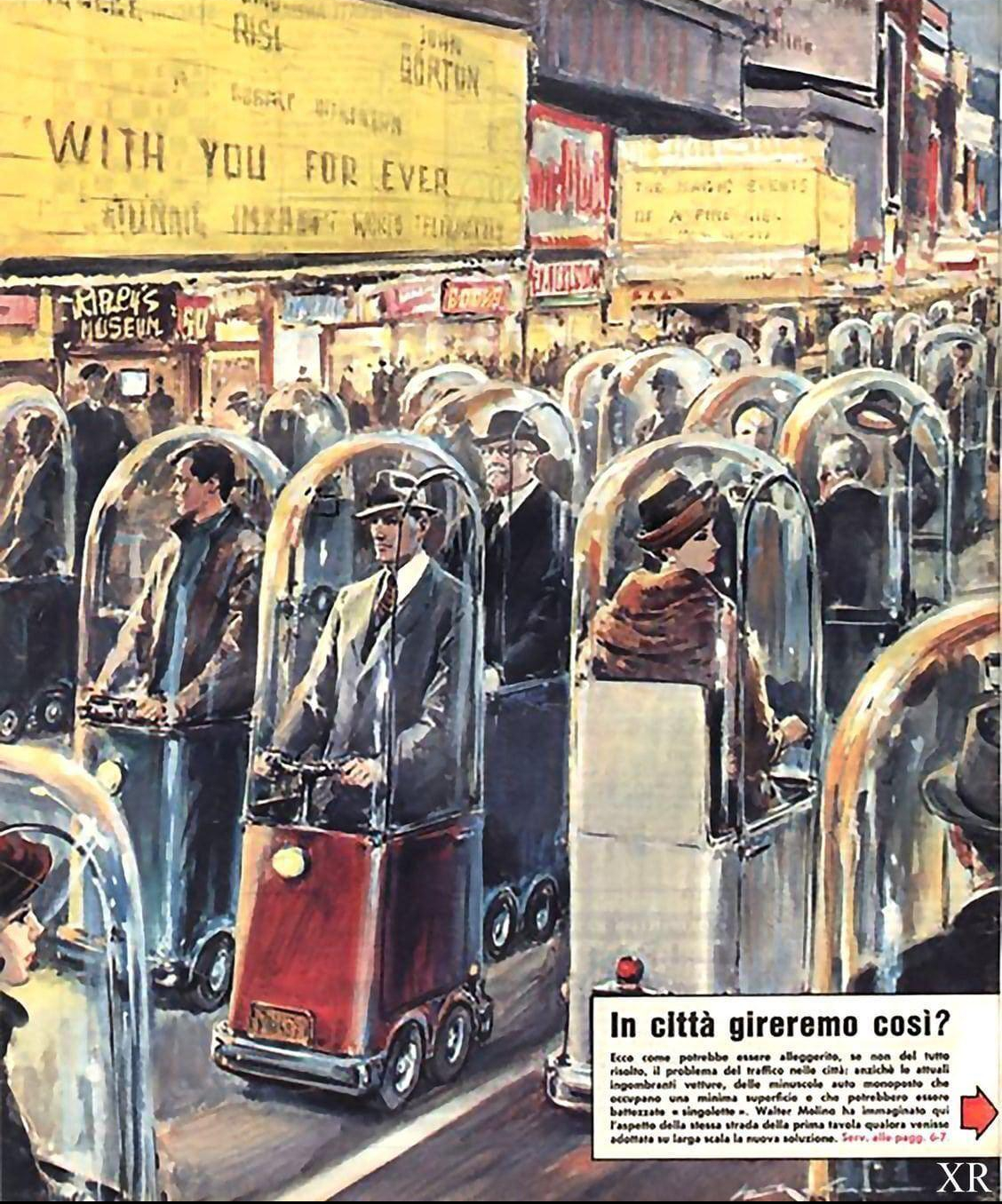

It is unclear why people in the 1950s thought this was a practical way to travel; not only it looks like it is impossible to breathe in there, who would want to stand upright while driving? It would definitely ease the traffic; however, probably no one would want to use it.

It is unclear why people in the 1950s thought this was a practical way to travel; not only it looks like it is impossible to breathe in there, who would want to stand upright while driving? It would definitely ease the traffic; however, probably no one would want to use it. Towering transmitters in the city and private-jet traffic in the sky… This is a prediction that was made probably too early and it is definitely not so far from reality. Today, we paint a similar future for smart-cities and sci-fi movies depict the future cities in the same manner. It seems that older generations and we have a similar vision of the future look of the world.

Towering transmitters in the city and private-jet traffic in the sky… This is a prediction that was made probably too early and it is definitely not so far from reality. Today, we paint a similar future for smart-cities and sci-fi movies depict the future cities in the same manner. It seems that older generations and we have a similar vision of the future look of the world.

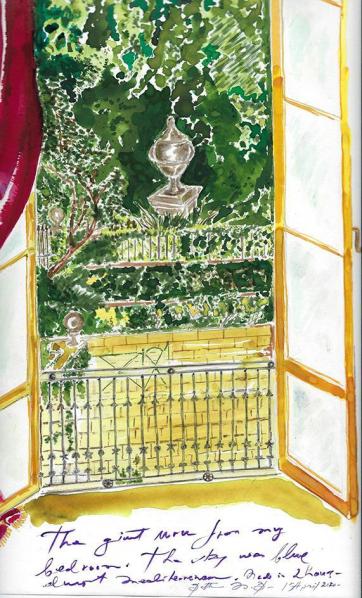

I became engrossed in Mitchell’s drawings while browsing the book—they’re vivid, intimate—but her handwritten lyrics and poems are just as revelatory. It’s hard not to think about art-making of any kind as an alchemical process, in which feelings and experiences go in and something else comes out. Whatever happens in between is mysterious, if not sublime: suddenly, an ordinary sensation is made beautiful. Our most profound writers do this work with ease, or at least appear to. Mitchell’s lyrics are never overworked or self-conscious, and she manages to be precise in her descriptions while remaining ambiguous about what’s right and what’s wrong; in her songs, the cures and the diseases are sometimes indistinguishable.

I became engrossed in Mitchell’s drawings while browsing the book—they’re vivid, intimate—but her handwritten lyrics and poems are just as revelatory. It’s hard not to think about art-making of any kind as an alchemical process, in which feelings and experiences go in and something else comes out. Whatever happens in between is mysterious, if not sublime: suddenly, an ordinary sensation is made beautiful. Our most profound writers do this work with ease, or at least appear to. Mitchell’s lyrics are never overworked or self-conscious, and she manages to be precise in her descriptions while remaining ambiguous about what’s right and what’s wrong; in her songs, the cures and the diseases are sometimes indistinguishable.  Joni Mitchell, in the foreword to “

Joni Mitchell, in the foreword to “