From NPR podcast of Fresh Air with Terry Gross:

Rieder likens his experiences trying to get off prescription pain meds to a game of hot potato. “The patient is the potato,” he says. “Everybody had a reason to send me to somebody else.”

Rieder likens his experiences trying to get off prescription pain meds to a game of hot potato. “The patient is the potato,” he says. “Everybody had a reason to send me to somebody else.”

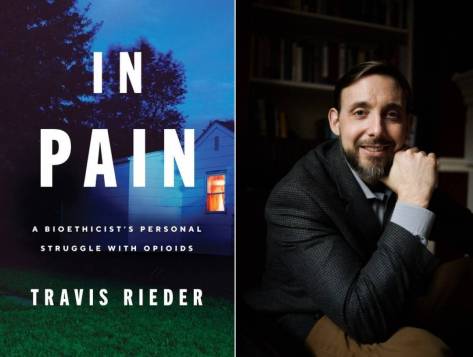

Eventually Rieder was able to wean himself off the drugs, but not before receiving bad advice and going through intense periods of withdrawal. He shares his insights as both a patient and a bioethicist in a new book, In Pain: A Bioethicist’s Personal Struggle With Opioids.

Press play button above to hear interview.

In 2015, Travis Rieder, a medical bioethicist with Johns Hopkins University’s Berman Institute of Bioethics, was involved in a motorcycle accident that crushed his left foot. In the months that followed, he underwent six different surgeries as doctors struggled first to save his foot and then to reconstruct it.

Rieder says that each surgery brought a new wave of pain, sometimes “searing and electrical,” other times “fiery and shocking.” Doctors tried to mitigate the pain by prescribing large doses of opioids, including morphine, fentanyl, Dilaudid, oxycodone and OxyContin. But when it came time to taper off the drugs, Rieder found it nearly impossible to get good advice from any of the clinicians who had treated him.

Read more

The learning curve was steep: “I couldn’t read; I couldn’t write. I could see the hospital signs, the elevator signs, the therapists’ cards, but I couldn’t understand them,” he wrote. The aphasia — the inability to understand or express speech — “had beaten and battered” his pride.

The learning curve was steep: “I couldn’t read; I couldn’t write. I could see the hospital signs, the elevator signs, the therapists’ cards, but I couldn’t understand them,” he wrote. The aphasia — the inability to understand or express speech — “had beaten and battered” his pride.

“The doctor asked whether he was sure that he had not taken anything else when he was sick? No acetaminophen? No herbs or supplements? The man was certain. Moreover, his labs were abnormal even before he took the antibiotics. The doctor hypothesized that the man’s liver had been a little inflamed from some minor injury — maybe a virus or other exposure — and the antibiotic, which is cleared through the liver, somehow added insult to injury.”

“The doctor asked whether he was sure that he had not taken anything else when he was sick? No acetaminophen? No herbs or supplements? The man was certain. Moreover, his labs were abnormal even before he took the antibiotics. The doctor hypothesized that the man’s liver had been a little inflamed from some minor injury — maybe a virus or other exposure — and the antibiotic, which is cleared through the liver, somehow added insult to injury.”

“Doctors and patients are increasingly recognizing the benefits of palliative care. People want care that helps them live as well as possible for as long as possible. Once people learn what palliative care is, they want it. So we’re training experts to meet this growing demand. We have one of the largest fellowship programs in the state, and we also train nursing students, medical students, and residents. We want all clinicians to know the basics of palliative care: how to manage pain, shortness of breath, and nausea and how to talk to patients about the things that matter most to them.”

“Doctors and patients are increasingly recognizing the benefits of palliative care. People want care that helps them live as well as possible for as long as possible. Once people learn what palliative care is, they want it. So we’re training experts to meet this growing demand. We have one of the largest fellowship programs in the state, and we also train nursing students, medical students, and residents. We want all clinicians to know the basics of palliative care: how to manage pain, shortness of breath, and nausea and how to talk to patients about the things that matter most to them.”

From time immemorial, an invariable feature of doctor–patient interaction has been that it takes place in person. But the status quo is changing. A large portion of patient care might eventually be delivered via telemedicine by virtualists, physicians who treat patients they may never meet.

From time immemorial, an invariable feature of doctor–patient interaction has been that it takes place in person. But the status quo is changing. A large portion of patient care might eventually be delivered via telemedicine by virtualists, physicians who treat patients they may never meet.

Fragility fractures occur in structurally weak bones due to aging and bone loss – osteoporosis. Dr. Anthony Ding explains what “fragility fractures” are, where they occur, what they mean to you, and how they are treated. Series: “Mini Medical School for the Public”.

Fragility fractures occur in structurally weak bones due to aging and bone loss – osteoporosis. Dr. Anthony Ding explains what “fragility fractures” are, where they occur, what they mean to you, and how they are treated. Series: “Mini Medical School for the Public”.

“Will price transparency lower health care costs? Economic theory and hospital opposition suggest it would, but the answer is not as straightforward as you might expect and could differ from market to market. Health care is a

“Will price transparency lower health care costs? Economic theory and hospital opposition suggest it would, but the answer is not as straightforward as you might expect and could differ from market to market. Health care is a