From a MyModernMet.com online article:

Since I work as a fine artist now, there are fewer commercial entities to please, so I’ve discovered something that should have been very obvious. If you want to engage the viewer, don’t tell them everything, encourage them to ask their own questions. An artist should not describe—he or she should interpret. If you design into your work a bit of mystery—areas where the viewer must “fill in the blanks”—you set up an unspoken dialog with your viewers and an emotional weight will begin to develop organically. This is just one example of course, but an important one.

Since I work as a fine artist now, there are fewer commercial entities to please, so I’ve discovered something that should have been very obvious. If you want to engage the viewer, don’t tell them everything, encourage them to ask their own questions. An artist should not describe—he or she should interpret. If you design into your work a bit of mystery—areas where the viewer must “fill in the blanks”—you set up an unspoken dialog with your viewers and an emotional weight will begin to develop organically. This is just one example of course, but an important one.

Artist Thomas W. Schaller combines a passion for architecture and storytelling into emotional landscape watercolor paintings. Originally trained as an architect, he found himself drawn to images of the built environment and eventually left designing behind to pursue fine art on a full-time basis. His education places him in an ideal position for architecture painting. Schaller understands how to design structures and knows what attributes to include and what he should leave out. At the same time, he’s able to tap into the feelings we get from visiting a city—such as a sentimentality—to produce pieces that are both beautiful and alluring.

James McElhinney: Discover the Hudson Anew presents the painter’s sketch books and prints related to the River in a comprehensive showing for the first time. A video program, animating turning pages, will allow visitors to see additional sketchbook paintings. McElhinney says he wants his art to demonstrate “that constructive dialogue between humanity and nature is alive and well, while underscoring how art provides durable and dynamic modes of engagement.”

James McElhinney: Discover the Hudson Anew presents the painter’s sketch books and prints related to the River in a comprehensive showing for the first time. A video program, animating turning pages, will allow visitors to see additional sketchbook paintings. McElhinney says he wants his art to demonstrate “that constructive dialogue between humanity and nature is alive and well, while underscoring how art provides durable and dynamic modes of engagement.”

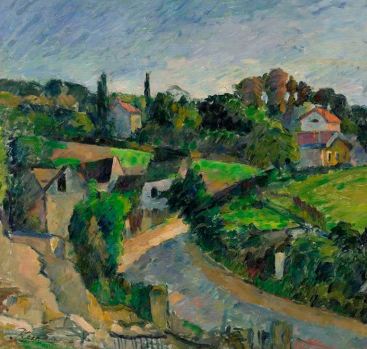

While all of the works on exhibit hold special interest, Aurisch identifies several gems. For example, Van Gogh fans will enjoy his spectacular perspectival rooftop view from the window of his room in The Hague in 1882. Maurice de Vlaminc’s 1906 Dancer at the “Rat Mort” (La danseuse du “Rat Mort”) is a delight with his Fauve treatment of the figure; through color and gestural line, it’s as though we are witnessing a shift into the 20th century. And Henri Matisse’s 1943 still life titled Lemons against a Fleur-de-lis Background (Citrons sur fond rose fleurdelisé) vibrates with lively pink patterned wallpaper and a stacked brick platform, charged with Japonisme energy.

While all of the works on exhibit hold special interest, Aurisch identifies several gems. For example, Van Gogh fans will enjoy his spectacular perspectival rooftop view from the window of his room in The Hague in 1882. Maurice de Vlaminc’s 1906 Dancer at the “Rat Mort” (La danseuse du “Rat Mort”) is a delight with his Fauve treatment of the figure; through color and gestural line, it’s as though we are witnessing a shift into the 20th century. And Henri Matisse’s 1943 still life titled Lemons against a Fleur-de-lis Background (Citrons sur fond rose fleurdelisé) vibrates with lively pink patterned wallpaper and a stacked brick platform, charged with Japonisme energy.

Rediscovered in the late 19th century, celebrated by authors, acknowledged and embraced by the 20th century avant-garde, the artist has enjoyed the dual prestige of tradition and modernity, linking Titian to the Fauvists and Mannerism to Cubism, Expressionism, Vorticism and Abstraction up to the Action painting.

Rediscovered in the late 19th century, celebrated by authors, acknowledged and embraced by the 20th century avant-garde, the artist has enjoyed the dual prestige of tradition and modernity, linking Titian to the Fauvists and Mannerism to Cubism, Expressionism, Vorticism and Abstraction up to the Action painting.

I describe myself as an urban-based painter who is interested in green spaces. Painting and drawing have been seen as profoundly unfashionable for most of my working life, and I have felt sometimes that it was quite eccentric to be a figurative painter with conventional subject matter. Looking back, my insistence on maintaining my practice as a figurative painter now seems more radical than conventional.

I describe myself as an urban-based painter who is interested in green spaces. Painting and drawing have been seen as profoundly unfashionable for most of my working life, and I have felt sometimes that it was quite eccentric to be a figurative painter with conventional subject matter. Looking back, my insistence on maintaining my practice as a figurative painter now seems more radical than conventional.

I was very blessed to have the opportunity to catch up with Hogan ahead of her Mayfair exhibition. I find myself entranced by her vibrant paintings that are dense with detail, filling the canvas from edge to edge with layers upon layers of paint. She has also established portraiture practice, her commissions including HRH The Prince of Wales. In a unique style, Hogan paints her sitters whilst they are deep in conversation, capturing unguarded gestures and expressions to create intricate portraits of both honesty and intimacy.

I was very blessed to have the opportunity to catch up with Hogan ahead of her Mayfair exhibition. I find myself entranced by her vibrant paintings that are dense with detail, filling the canvas from edge to edge with layers upon layers of paint. She has also established portraiture practice, her commissions including HRH The Prince of Wales. In a unique style, Hogan paints her sitters whilst they are deep in conversation, capturing unguarded gestures and expressions to create intricate portraits of both honesty and intimacy.

Things take an even stranger turn when he gets to Egypt, and his own features still appear again and again; not, as before, as a barely significant detail in an otherwise busy composition, but as a principal element. In a series of fine single-figure paintings brought together at the Watts Gallery, Lewis represents himself as a Syrian sheikh scanning the horizon of the Sinai desert; as the suave ‘bey’ of a Cairene household, lowering his eyelids as his servant offers him a water pipe; as an impassive carpet-seller in the Bezestein bazaar

Things take an even stranger turn when he gets to Egypt, and his own features still appear again and again; not, as before, as a barely significant detail in an otherwise busy composition, but as a principal element. In a series of fine single-figure paintings brought together at the Watts Gallery, Lewis represents himself as a Syrian sheikh scanning the horizon of the Sinai desert; as the suave ‘bey’ of a Cairene household, lowering his eyelids as his servant offers him a water pipe; as an impassive carpet-seller in the Bezestein bazaar

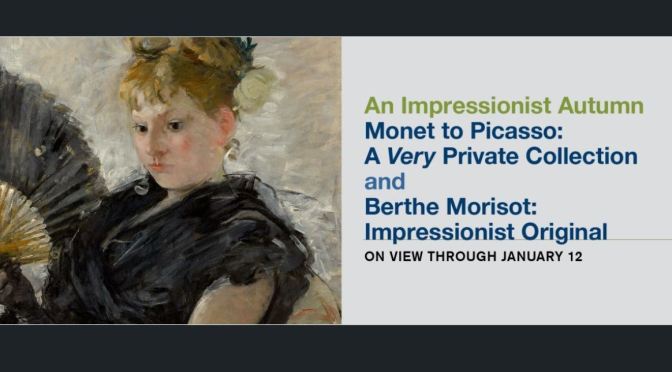

Édouard Manet was a provocateur and a dandy, the Impressionist generation’s great painter of modern Paris. This first-ever exhibition to explore the last years of Manet’s short life and career reveals a fresh and surprisingly intimate aspect of this celebrated artist’s work. Stylish portraits,

Édouard Manet was a provocateur and a dandy, the Impressionist generation’s great painter of modern Paris. This first-ever exhibition to explore the last years of Manet’s short life and career reveals a fresh and surprisingly intimate aspect of this celebrated artist’s work. Stylish portraits,  luscious still lifes, delicate pastels and watercolors, and vivid café and garden scenes convey Manet’s elegant social world and reveal his growing fascination with fashion, flowers, and his view of the parisienne—a feminine embodiment of modern life in all its particular, fleeting beauty.

luscious still lifes, delicate pastels and watercolors, and vivid café and garden scenes convey Manet’s elegant social world and reveal his growing fascination with fashion, flowers, and his view of the parisienne—a feminine embodiment of modern life in all its particular, fleeting beauty.

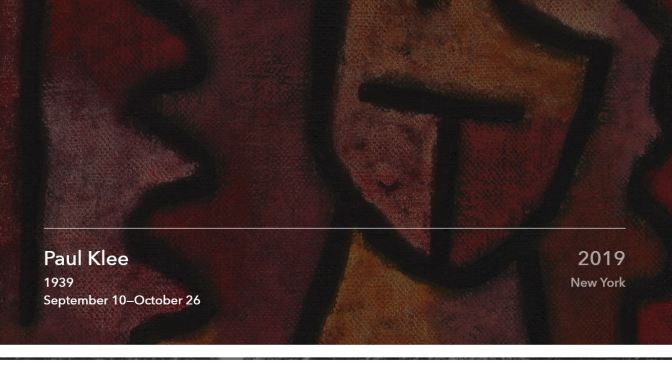

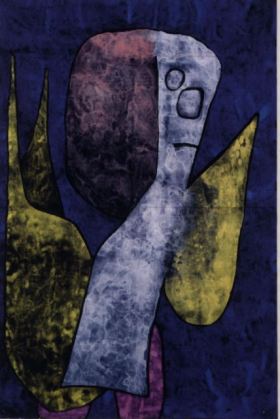

The works on view illustrate how Klee responded to his personal difficulties and the broader social realities of the time through imagery that is at turns political, solemn, playful, humorous, and poetic. Ranging in subject matter, the works all testify to Klee’s restless drive to experiment with his forms and materials, which include adhesive, grease, oil, chalk, and watercolor, among others, resulting in surfaces that are not only visually striking, but also highly tactile and original. The novelty and ingenuity of Klee’s late works informed the art of the generation of artists that emerged after World War II, and they continue to hold relevance and allure for artists and viewers alike today.

The works on view illustrate how Klee responded to his personal difficulties and the broader social realities of the time through imagery that is at turns political, solemn, playful, humorous, and poetic. Ranging in subject matter, the works all testify to Klee’s restless drive to experiment with his forms and materials, which include adhesive, grease, oil, chalk, and watercolor, among others, resulting in surfaces that are not only visually striking, but also highly tactile and original. The novelty and ingenuity of Klee’s late works informed the art of the generation of artists that emerged after World War II, and they continue to hold relevance and allure for artists and viewers alike today.

Witness to the radical aesthetics that gripped Paris in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Vallotton developed his own singular voice. Today we recognize him as a distinctive artist of his generation. His lampooning wit, subversive satire, and wry humor is apparent everywhere in his artistic production. Vallotton’s trenchant woodcuts of the 1890s solidified his reputation as a printmaker of the first rank while boldly messaging his left-wing politics.

Witness to the radical aesthetics that gripped Paris in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Vallotton developed his own singular voice. Today we recognize him as a distinctive artist of his generation. His lampooning wit, subversive satire, and wry humor is apparent everywhere in his artistic production. Vallotton’s trenchant woodcuts of the 1890s solidified his reputation as a printmaker of the first rank while boldly messaging his left-wing politics. dozen lenders. Swiss-born and Paris-educated, Vallotton (1865–1925) created lasting imagery of fin-de-siècle Paris.

dozen lenders. Swiss-born and Paris-educated, Vallotton (1865–1925) created lasting imagery of fin-de-siècle Paris.

Though his paintings and sculptures sell all over the world for fabulous prices, he has not enriched himself. He lives simply, with his wife, Trine Ellitsgaard Lopez, an accomplished weaver, in a traditional house in the middle of Oaxaca, and has used his considerable profits to found art centers and museums, an ethnobotanical garden and at least three libraries.

Though his paintings and sculptures sell all over the world for fabulous prices, he has not enriched himself. He lives simply, with his wife, Trine Ellitsgaard Lopez, an accomplished weaver, in a traditional house in the middle of Oaxaca, and has used his considerable profits to found art centers and museums, an ethnobotanical garden and at least three libraries. Toledo, whose origins were obscure and inauspicious, was the son of a leatherworker—shoemaker and tanner. He was born in Mexico City, but the family soon after moved to their ancestral village near Juchitán de Zaragoza in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, nearer to Guatemala than to Mexico City—and being ethnically Zapotec, nearer culturally to the ancient pieties of the hinterland too.

Toledo, whose origins were obscure and inauspicious, was the son of a leatherworker—shoemaker and tanner. He was born in Mexico City, but the family soon after moved to their ancestral village near Juchitán de Zaragoza in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, nearer to Guatemala than to Mexico City—and being ethnically Zapotec, nearer culturally to the ancient pieties of the hinterland too.