Foreign Policy (September 20, 2024): The Mediterranean was the backdrop for much of FP’s summer reading. For the first installment of our new column about international fiction, we travel to two very different settings along this vast sea: Muammar al-Qaddafi’s Libya and modern Sicily. Plus, we highlight the buzziest releases in international fiction this month.

My Friends: A Novel

Hisham Matar (Random House, 416 pp., $28.99, January 2024)

Hisham Matar’s latest novel, recently longlisted for the 2024 Booker Prize, is about friendship and exile. Matar, a Libyan American writer based in London, was raised in a family of anti-Qaddafi dissidents and has made the tyrant’s maniacal rule the subject of most of his work.

In My Friends, Matar follows protagonist and narrator Khaled from his school days in Benghazi to the period following Qaddafi’s overthrow in 2011. After attending a 1984 anti-Qaddafi demonstration in London and landing on the dictator’s hit list, Khaled is forced to upend his quiet life as a university student in Edinburgh and start over in the British capital. (The real-life protest, where officials at the Libyan Embassy shot several protesters and killed a police officer, led Libya and Britain to sever ties.)

Khaled develops strong friendships with two fellow Libyans in London, Hosam and Mustafa. Unlike Khaled, both are unwavering in their political convictions. Although Khaled is opposed to Qaddafi’s regime, he is also aware of the costs—and futility—of speaking out. That Khaled’s criticism of Qaddafi’s Libya never leaves the private, rhetorical sphere is a point of contention between him and his friends. Ultimately, Hosam and Mustafa return to Libya in 2011 to join the militias fighting Qaddafi; Khaled remains in Britain, deeply insecure about his inaction.

Khaled’s decision to attend the 1984 protest was one he made hesitantly, so it is all the more shocking that his first brush with activism fundamentally altered the course of his life. Khaled’s father, an academic who resigned himself to a mid-level career under Qaddafi to avoid repression, had taught his son that it is “almost always best to leave things be.”

At its core, My Friends is a debate over whether, in the face of repression, such silence is a form of self-preservation or cowardice. This tension exists between the book’s main characters—the friends—as well as within Khaled’s own head. While Khaled’s exile led him to make great friends, his time in London is equally a painful experience of solitude. With Libyan phone lines tapped and mail pilfered by the regime, he has had to uphold a decades-long lie to his family about why he can no longer return home—all because he attended a single protest.

An author with an agenda might have sought to portray Hosam and Mustafa as valiant fighters whose sacrifices are rewarded, opposite Khaled, who prefers comfort to confrontation. But Libyan history does not follow a morally righteous narrative arc. At the end of the book, Libya becomes enveloped in a new crisis, and each friend seeks to find his place within it.—Allison Meakem

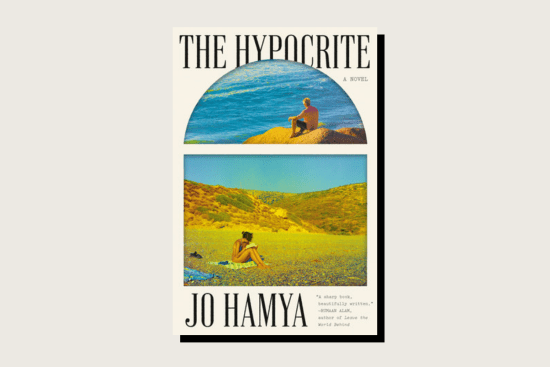

The Hypocrite: A Novel

Jo Hamya (Pantheon, 240 pp., $26, August 2024)

The Mediterranean is a time-honored stage for the psychosocial dramas of the elite. From British novelist John Fowles’s 1965 masterpiece, The Magus, to the entire Mamma Mia! franchise, fictional foreigners have long flocked to Greek and Italian isles to escape from—and, more often, confront—their heartbreaks and pathologies and familial squabbles. Often left out of these tales are the locals.

The Hypocrite by British author Jo Hamya at first seems like more of the same. It takes place over the course of one staging of a play about a summer that Sophia, the young playwright, once spent in Sicily’s Aeolian Islands with her father, a famous novelist whose work has aged poorly. It’s a smooth and often witty portrait of the upper-middle-class London art scene, written in the streamlined Rachel Cusk-esque register that defines much contemporary literary fiction.

Yet The Hypocrite also attempts to do something more. Although Sophia’s family dramas make up the bulk of the narrative, Hamya eventually shifts her focus to the family’s housekeeper in Sicily. She recalls that Sophia “was demanding in the worst way an English tourist could be.” Sophia didn’t try to learn even a little Italian. She and her father, the housekeeper thinks, were “lazy, messy people” who never bothered “to make her job easier with the simplest of acts.”

Hamya’s novel is part of the recent trend of examining who, historically, has been omitted in traditional narratives, especially ones set in locales that are under-resourced, exoticized, and deeply reliant on tourism. (Sicilians are European, yes, but they also live in one of Italy’s poorest regions.) In this regard, the novel is closer in spirit to HBO’s The White Lotus, the much-lauded send-up of the rich at a luxury resort chain (first in Hawaii, then in Sicily, and soon in Thailand), than many of its other predecessors.

Hamya does not dwell, however, on this upstairs-downstairs dynamic. Rather than skewering the careless interlopers, she aims for a bit more nuance, attending—if only fleetingly—to both the narrower interests of her protagonists and the invisible hands that helped set the stage for them that summer.—Chloe Hadavas