From a New Yorker online article:

I became engrossed in Mitchell’s drawings while browsing the book—they’re vivid, intimate—but her handwritten lyrics and poems are just as revelatory. It’s hard not to think about art-making of any kind as an alchemical process, in which feelings and experiences go in and something else comes out. Whatever happens in between is mysterious, if not sublime: suddenly, an ordinary sensation is made beautiful. Our most profound writers do this work with ease, or at least appear to. Mitchell’s lyrics are never overworked or self-conscious, and she manages to be precise in her descriptions while remaining ambiguous about what’s right and what’s wrong; in her songs, the cures and the diseases are sometimes indistinguishable.

I became engrossed in Mitchell’s drawings while browsing the book—they’re vivid, intimate—but her handwritten lyrics and poems are just as revelatory. It’s hard not to think about art-making of any kind as an alchemical process, in which feelings and experiences go in and something else comes out. Whatever happens in between is mysterious, if not sublime: suddenly, an ordinary sensation is made beautiful. Our most profound writers do this work with ease, or at least appear to. Mitchell’s lyrics are never overworked or self-conscious, and she manages to be precise in her descriptions while remaining ambiguous about what’s right and what’s wrong; in her songs, the cures and the diseases are sometimes indistinguishable.

Joni Mitchell, in the foreword to “Morning Glory on the Vine,” her new book of lyrics and illustrations, explains that, in the early nineteen-seventies, just as her fervent and cavernous folk songs were finding a wide audience, she was growing less interested in making music than in drawing. “Once when I was sketching my audience in Central Park, they had to drag me onto the stage,” she writes. Though Mitchell is deeply beloved for her music—her album “Blue” is widely considered one of the greatest LPs of the album era and is still discussed, nearly fifty years later, in reverent, almost disbelieving whispers—she has consistently defined herself as a visual artist. “I have always thought of myself as a painter derailed by circumstance,” she told the Globe and Mail, in 2000. At the very least, painting was where she directed feelings of wonderment and relish. “I sing my sorrow and I paint my joy,” is how she put it.

Joni Mitchell, in the foreword to “Morning Glory on the Vine,” her new book of lyrics and illustrations, explains that, in the early nineteen-seventies, just as her fervent and cavernous folk songs were finding a wide audience, she was growing less interested in making music than in drawing. “Once when I was sketching my audience in Central Park, they had to drag me onto the stage,” she writes. Though Mitchell is deeply beloved for her music—her album “Blue” is widely considered one of the greatest LPs of the album era and is still discussed, nearly fifty years later, in reverent, almost disbelieving whispers—she has consistently defined herself as a visual artist. “I have always thought of myself as a painter derailed by circumstance,” she told the Globe and Mail, in 2000. At the very least, painting was where she directed feelings of wonderment and relish. “I sing my sorrow and I paint my joy,” is how she put it.

To read more: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/joni-mitchell-discusses-her-new-book-of-early-songs-and-drawings

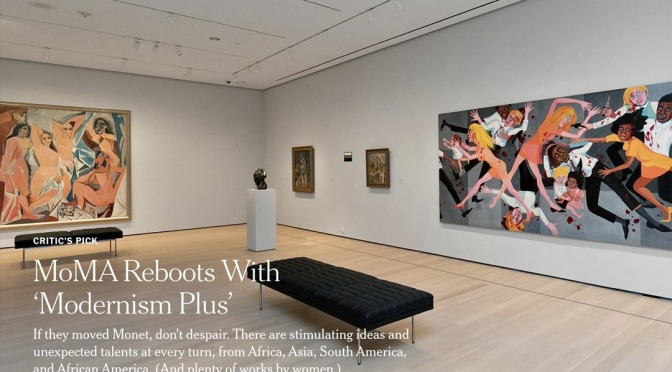

There’s also a special focus on architecture and design in this new approach to the collection: Several galleries are devoted to various aspects of those fields, including “The Vertical City,” an examination of skyscraper construction that includes photos by Berenice Abbott, Hugh Ferriss’s architectural drawings, and other ephemera. Elsewhere, building models of the Guggenheim and a spec design of MoMA by modernist master William Lescaze emphasize the importance of architecture to museums, and vice versa.

There’s also a special focus on architecture and design in this new approach to the collection: Several galleries are devoted to various aspects of those fields, including “The Vertical City,” an examination of skyscraper construction that includes photos by Berenice Abbott, Hugh Ferriss’s architectural drawings, and other ephemera. Elsewhere, building models of the Guggenheim and a spec design of MoMA by modernist master William Lescaze emphasize the importance of architecture to museums, and vice versa.

Things take an even stranger turn when he gets to Egypt, and his own features still appear again and again; not, as before, as a barely significant detail in an otherwise busy composition, but as a principal element. In a series of fine single-figure paintings brought together at the Watts Gallery, Lewis represents himself as a Syrian sheikh scanning the horizon of the Sinai desert; as the suave ‘bey’ of a Cairene household, lowering his eyelids as his servant offers him a water pipe; as an impassive carpet-seller in the Bezestein bazaar

Things take an even stranger turn when he gets to Egypt, and his own features still appear again and again; not, as before, as a barely significant detail in an otherwise busy composition, but as a principal element. In a series of fine single-figure paintings brought together at the Watts Gallery, Lewis represents himself as a Syrian sheikh scanning the horizon of the Sinai desert; as the suave ‘bey’ of a Cairene household, lowering his eyelids as his servant offers him a water pipe; as an impassive carpet-seller in the Bezestein bazaar

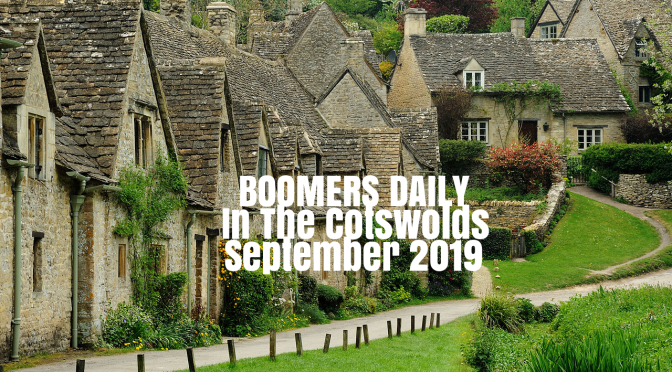

A brisk 2.9 mile walk (yes, 2.9 miles) in mildly drizzly weather from The Swan Hotel door back to the breakfast room set up a perfect day.

A brisk 2.9 mile walk (yes, 2.9 miles) in mildly drizzly weather from The Swan Hotel door back to the breakfast room set up a perfect day.

But there is nothing quite like the mind-bending spectacle now on display at dusk in the hills of Paso Robles here, a popular wine destination. That is the witching hour when thousands of solar-powered glass orbs on stems, created by the artist Bruce Munro, enfold visitors in an earthbound aurora borealis of shifting hues.

But there is nothing quite like the mind-bending spectacle now on display at dusk in the hills of Paso Robles here, a popular wine destination. That is the witching hour when thousands of solar-powered glass orbs on stems, created by the artist Bruce Munro, enfold visitors in an earthbound aurora borealis of shifting hues.

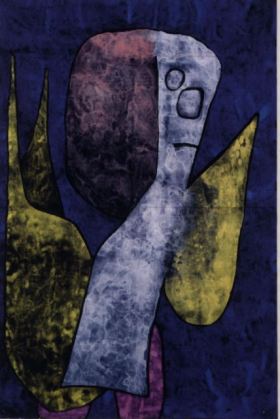

The works on view illustrate how Klee responded to his personal difficulties and the broader social realities of the time through imagery that is at turns political, solemn, playful, humorous, and poetic. Ranging in subject matter, the works all testify to Klee’s restless drive to experiment with his forms and materials, which include adhesive, grease, oil, chalk, and watercolor, among others, resulting in surfaces that are not only visually striking, but also highly tactile and original. The novelty and ingenuity of Klee’s late works informed the art of the generation of artists that emerged after World War II, and they continue to hold relevance and allure for artists and viewers alike today.

The works on view illustrate how Klee responded to his personal difficulties and the broader social realities of the time through imagery that is at turns political, solemn, playful, humorous, and poetic. Ranging in subject matter, the works all testify to Klee’s restless drive to experiment with his forms and materials, which include adhesive, grease, oil, chalk, and watercolor, among others, resulting in surfaces that are not only visually striking, but also highly tactile and original. The novelty and ingenuity of Klee’s late works informed the art of the generation of artists that emerged after World War II, and they continue to hold relevance and allure for artists and viewers alike today.

This focused installation features pastels by four artists whose work was shown in the Impressionist exhibitions: Mary Cassatt, Edgar Degas, Eva Gonzalès, and Berthe Morisot. Their subjects range from scenes of modern life, such as ballet performers and a woman working in a hat shop, to depictions of intimate moments of bathing and women with children.

This focused installation features pastels by four artists whose work was shown in the Impressionist exhibitions: Mary Cassatt, Edgar Degas, Eva Gonzalès, and Berthe Morisot. Their subjects range from scenes of modern life, such as ballet performers and a woman working in a hat shop, to depictions of intimate moments of bathing and women with children. Pastel, a medium used to draw on paper or, less often, on canvas, is made by combining dry pigment with a sticky binder. Once artists have applied the pastel to the surface, they can either blend it, leave their markings visible, or layer different colors to create texture and tone. Pastel portraits had previously gained popularity in France and England in the 18th century, but fell out of fashion with critics when pastel was deemed too feminine; not only was it used by women artists, but it had a powdery consistency similar to women’s makeup. The Impressionists rejected this bias and instead embraced the medium’s ability to impart immediacy, boldness, and radiance.

Pastel, a medium used to draw on paper or, less often, on canvas, is made by combining dry pigment with a sticky binder. Once artists have applied the pastel to the surface, they can either blend it, leave their markings visible, or layer different colors to create texture and tone. Pastel portraits had previously gained popularity in France and England in the 18th century, but fell out of fashion with critics when pastel was deemed too feminine; not only was it used by women artists, but it had a powdery consistency similar to women’s makeup. The Impressionists rejected this bias and instead embraced the medium’s ability to impart immediacy, boldness, and radiance.

In some cases, Wyeth’s images bore into memory as sharply as the books they illuminate. I’m thankful I never saw Wyeth’s “Captain Nemo” (1918) while steeping myself in Jules Verne’s “The Mysterious Island” (1874): I would never have been able to shed the image Wyeth created of this white-haired, secretive, dying man, surrounded by allusions to his exotic past, his skin seeming bleached, we learn here, by the electrical lighting of his submarine.

In some cases, Wyeth’s images bore into memory as sharply as the books they illuminate. I’m thankful I never saw Wyeth’s “Captain Nemo” (1918) while steeping myself in Jules Verne’s “The Mysterious Island” (1874): I would never have been able to shed the image Wyeth created of this white-haired, secretive, dying man, surrounded by allusions to his exotic past, his skin seeming bleached, we learn here, by the electrical lighting of his submarine.