Our new issue is now online featuring @amiasrinivasan on bestiality, @rosalyster on Louisiana underwater, @adamshatz on Richard Wright, Colin Burrow on Christopher Ricks, @moonjets on Milman Parry, a poem by @ae_stallings and a cover by Alexander Gorlizki: https://t.co/xaTOjYd3Vr pic.twitter.com/5pZxNXgiwd

— London Review of Books (@LRB) September 29, 2021

Tag Archives: LRB

Literature: The London Review Of Books – Aug 12

Arts & Literature: A Close Reading Of Poet Robert Frost (LRB Podcast)

In the latest episode in their series of Close Readings, Seamus Perry and Mark Ford look at the life and work of Robert Frost, the great American poet of fences and dark woods.

In the latest episode in their series of Close Readings, Seamus Perry and Mark Ford look at the life and work of Robert Frost, the great American poet of fences and dark woods.

(August 4, 2020)

They discuss Frost’s difficult early life as an occasional poultry farmer and teacher, his arrival in England in 1912 amid the flowering of Georgian poetry, and his emergence as the first 20th-century professional poet, whose version of the American wilderness myth, full of mischief and foreboding, took him to packed concert halls and a presidential inauguration.

New Literary Podcasts: “Consider The Lemur” By Katherine Rundell (LRB)

It is probably best not to take advice direct and unfiltered from the animal kingdom – but lemurs are, I think, an exception. They live in matriarchal troops, with an alpha female at their head.

The first lemur I ever met was a female, and she tried to bite me, which was fair, because I was trying to touch her, and humans have done nothing to recommend themselves to lemurs. She was an indri lemur, living in a wildlife sanctuary outside Antananarivo; she had an infant, which was riding not on her front, like a baby monkey, but on her back, like a miniature Lester Piggott. She had wide yellow eyes. William Burroughs, in his lemur-centric eco-surrealist novella Ghost of Chance, described the eyes of a lemur as ‘changing colour with shifts of the light: obsidian, emerald, ruby, opal, amethyst, diamond’. The stare of this indri resembled that of a young man at a nightclub who urgently wishes to tell you about his belief system, but her fur was the softest thing I have ever touched. I was a child, and the indri, which is the largest extant species of lemur, came up to my ribs when standing on her hind legs. She looked, as lemurs do, like a cross between a monkey, a cat, a rat and a human.

Podcasts: “Drawing An Albatross With A Camera Lucida” By Gaby Wood (LRB)

Gaby Wood reads her diary from the latest issue of the LRB, in which she tries to draw an albatross using a camera lucida.

By the time I used the camera lucida in the museum, I’d spent several months grappling with the strange proposition offered by its prism. I’d read that the image was sharper if you held it over a dark drawing surface, but that didn’t make any sense to me until the smoked metal etching plate was beneath my hand. Suddenly the albatross skeleton appeared on it: bright, spectral. The process was different from the way I’d imagined it. There was a drag, almost a dance, under the needle – a tiny jump of resistance in the copper. Without seeing what you were doing, you could feel it more keenly. It wasn’t like ice-skating at all.

By the time I used the camera lucida in the museum, I’d spent several months grappling with the strange proposition offered by its prism. I’d read that the image was sharper if you held it over a dark drawing surface, but that didn’t make any sense to me until the smoked metal etching plate was beneath my hand. Suddenly the albatross skeleton appeared on it: bright, spectral. The process was different from the way I’d imagined it. There was a drag, almost a dance, under the needle – a tiny jump of resistance in the copper. Without seeing what you were doing, you could feel it more keenly. It wasn’t like ice-skating at all.

A camera lucida is an optical device used as a drawing aid by artists. The camera lucida performs an optical superimposition of the subject being viewed upon the surface upon which the artist is drawing. The artist sees both scene and drawing surface simultaneously, as in a photographic double exposure.

A camera lucida is an optical device used as a drawing aid by artists. The camera lucida performs an optical superimposition of the subject being viewed upon the surface upon which the artist is drawing. The artist sees both scene and drawing surface simultaneously, as in a photographic double exposure.

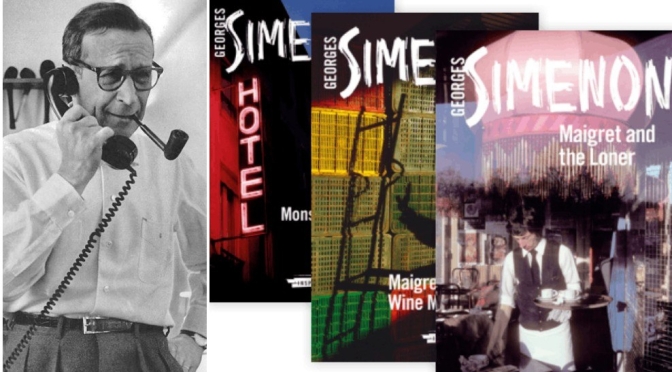

Podcast Profiles: Author Georges Simenon, Creator Of Inspector Maigret (LRB)

London Review of Books’ John Lanchester talks to Thomas Jones about Georges Simenon, whose output was so prodigious that even he didn’t know how many books he wrote.

TRANSCRIPT

TRANSCRIPT

Thomas Jones: Hello, and welcome to the London Review of Books podcast. My name is Thomas Jones, and today I’m talking to John Lanchester, who’s written a piece in the current issue of the LRB about Georges Simenon and his 75 Maigret novels, which Penguin have just finished reissuing in new translations. Hello, John.

John Lanchester: Hi Tom. Thanks for having me.

TJ: Thank you for joining me. And I thought we could begin where you begin your piece with Simenon’s ‘colossal output’, as you put it, and that nobody knows how many books he actually wrote, though it was probably more than four hundred, which is fewer than Barbara Cartland, but still puts the rest of us to shame.

JL: He didn’t half crack on, that’s true. Yes, he started as a young man in Liège, his home town in Belgium. And he got a job as a reporter on the local paper. I think he was not quite 16, which is properly strange. It’s like something out of a high concept kid’s TV show, you know, Georges Simenon – Boy Reporter, and very early on latched onto the idea of making money through writing.He began writing when he was 18, his first book came out when he was 19. He started writing every sort of potboiler, thrillers, romances, sort of semi-porn westerns, things like that, at an absolutely astounding rate of productivity. And his target was eighty pages a day, typewritten, and even on the assumption that the pages … I mean, a short page would be 150 words and it could well have been more, but it was 10,000 words a day, and he did that every single day. And then he’d write eighty pages, and then he’d go and be sick. Just from the physical and mental exertion and the strain. That was in the morning. And then he’d recover and do a bit of light reading and pottering about. And then the next day he did the same again, over and over and over for about seven years. And in that period, as you’ve mentioned, we don’t know exactly how many, because he forgot, and he had multiple pseudonyms. The main one being Georges Sim, which was how he was known when he began writing the Simenon novels. People thought that Simenon was a pseudonym because George Sim was so well known, but he seems to have written about 150 or more books in this seven-year burst. It makes you feel peculiar even to think about what that must have been like.

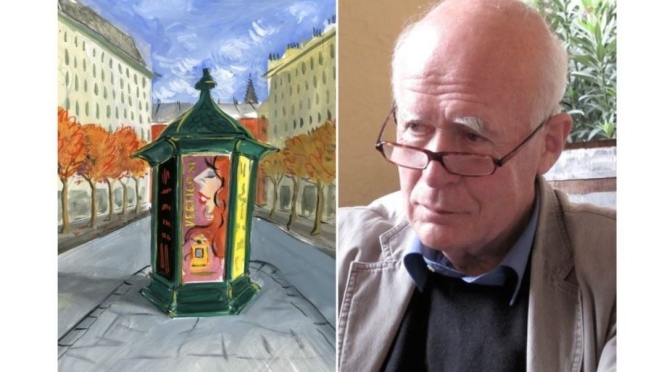

Literary Arts: New Website Archives Work Of British Illustrator And Designer Peter Campbell (1937-2011)

The website is about the work of the designer, writer and illustrator Peter Campbell (1937‑2011). The intention is to present an archive of Peter’s illustration, design and editorial work, as well as occasional selections from his writing.

When asked what he did for a living, Peter would usually say he was a designer, or, a typographer. Designing for print – books, exhibition catalogues, magazines, posters –  took up the most substantial part of his time, at the BBC in the 1960s and 1970s and thereafter as a freelance. He was also an illustrator, a journalist, an author of children’s books, an editor and a publisher. The great range of his professional work, and his encompassing interest in the work of others, made him a collaborator sought out by writers, publishers and artists.

took up the most substantial part of his time, at the BBC in the 1960s and 1970s and thereafter as a freelance. He was also an illustrator, a journalist, an author of children’s books, an editor and a publisher. The great range of his professional work, and his encompassing interest in the work of others, made him a collaborator sought out by writers, publishers and artists.

Diana Souhami, who worked with Peter often, wrote in the Guardian after his death: “He had the ability to conceptualise what each publishing project needed and to get it right. He was hugely and diversely productive, but seldom hit a wrong note.”

Discussing his journalism in her appreciation in the London Review, Mary‑Kay Wilmers wrote: “There are people whom getting a grip doesn’t suit, who don’t want to be confined. One can honour the world in depth or across a wide range and there were few aspects of the world that Peter didn’t wish to honour.”

He probably would have been delighted by – and certainly modestly sceptical of – Alan Bennett’s appraisal, in the posthumous publication of a catalogue of his pictures in Artwork, that he was “an heir to Ardizzone, Bawden and Ravilious.”

Peter Campbell was born in Wellington, New Zealand in 1937. In 1960 he emigrated to London where he lived for the rest of his life. He died in 2011.

Coronavirus/Covid-19: Francis Crick Institute On “Large-Scale, Reliable Testing” (LRB Podcast)

Rupert Beale talks again to Thomas Jones about his work at the Francis Crick Institute, where he’s helping to set up a testing lab for Covid-19.

Rupert Beale talks again to Thomas Jones about his work at the Francis Crick Institute, where he’s helping to set up a testing lab for Covid-19.

He talks about the challenges of creating a scalable process, explains why a successful antibody test could be hard to achieve, and finds some reasons to be hopeful.

You can find a full transcript of this episode HERE.