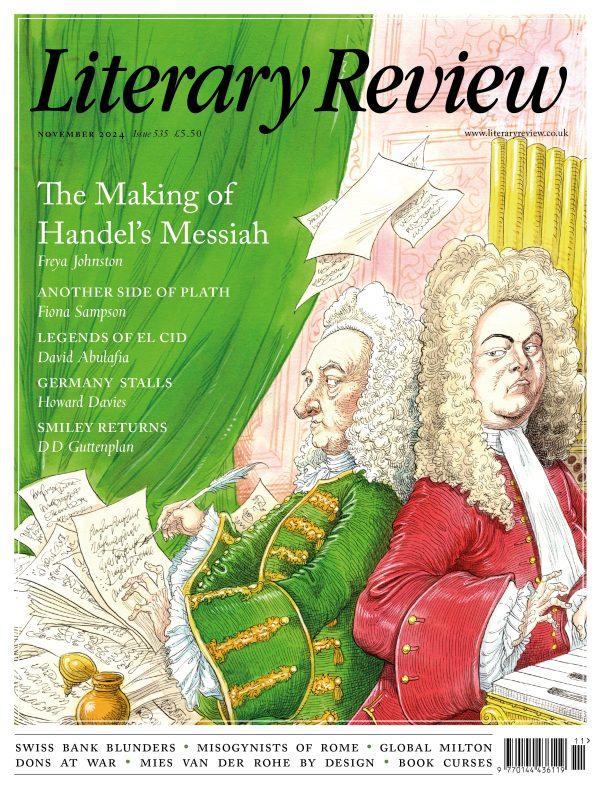

Literary Review – November 2, 2024: The latest issue features ‘The Making of Handel’s Messiah’; Another Side of Plath; Legends of El Cid; Germany Stalls and Smiley Returns…

Literary Review – November 2, 2024: The latest issue features ‘The Making of Handel’s Messiah’; Another Side of Plath; Legends of El Cid; Germany Stalls and Smiley Returns…

The New York Review of Books (October 31, 2024) – The latest issue features Coco Fusco on yearning to breathe free, Elaine Blair on Rachel Cusk, Fintan O’Toole on Trump’s predations, Ruth Bernard Yeazell on John Singer Sargent, Michelle Nijhuis on the disasters wrought by remaking nature for human ends, Clair Wills on Janet Frame, Andrew Raftery on the Declaration of Independence, Rozina Ali on evangelical missionaries in Afghanistan and Iraq, A.S. Hamrah on the Trump biopic, Tim Parks on Nathaniel Hawthorne, poems by John Kinsella and Emily Berry, and much more.

Two recent books about our immigration system reveal its long history of exploiting vulnerable individuals for financial gain.

Welcome the Wretched: In Defense of the “Criminal Alien” by César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández

In the Shadow of Liberty: The Invisible History of Immigrant Detention in the United States by Ana Raquel Minian

Two new books consider the delusion of the human quest to be free from the constraints of nature.

The Burning Earth: A History by Sunil Amrith

A Natural History of Empty Lots: Field Notes from Urban Edgelands, Back Alleys, and Other Wild Places by Christopher Brown

The Islamic Republic’s sordid proxy war with the West may now be leaving it open to an all-out attack as Israel attempts to eliminate its enemies throughout the region.

Wall Street Journal Books (October 21, 2024):

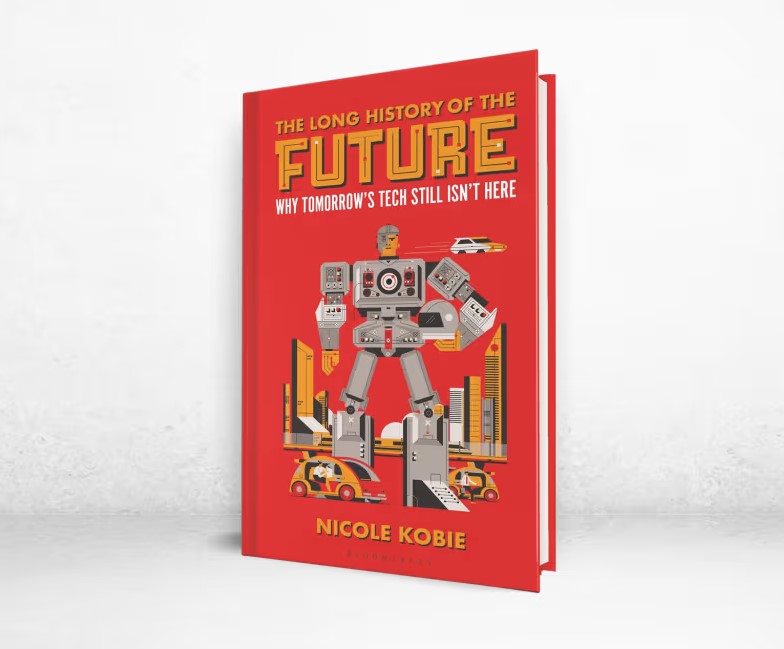

We don’t have flying cars or Jetsons-like robots to cook our meals. What we have is better: constant incremental progress.

The Long History of the Future: Why Tomorrow’s Technology Still Isn’t Here By Nicole Kobie

A video flickers to life as Dave Brubeck’s “Take Five” begins to sound. A long-haired man appears on screen. You might expect a jazz concert, but the man fiddles with a cabinet-like, camera-laden machine on wheels. As he steps away, a buzzer sounds, the machine slowly rolls forward, and the narrator announces its name: Shakey the Robot.

nature Magazine Science Book Reviews – October 14, 2024: Andrew Robinson reviews five of the best science picks.

Einstein’s Tutor

Lee Phillips PublicAffairs (2024)

Major studies of Albert Einstein’s work contain minimal, if any, reference to the role of German mathematician Emmy Noether. Yet, she was crucial in resolving a paradox in general relativity through her theorem connecting symmetry and energy-conservation laws, published in 1918. When Noether died in 1935, Einstein called her “the most significant creative mathematical genius thus far produced since the higher education of women began”. In this book about her for the general reader, physicist Lee Phillips brings Noether alive.

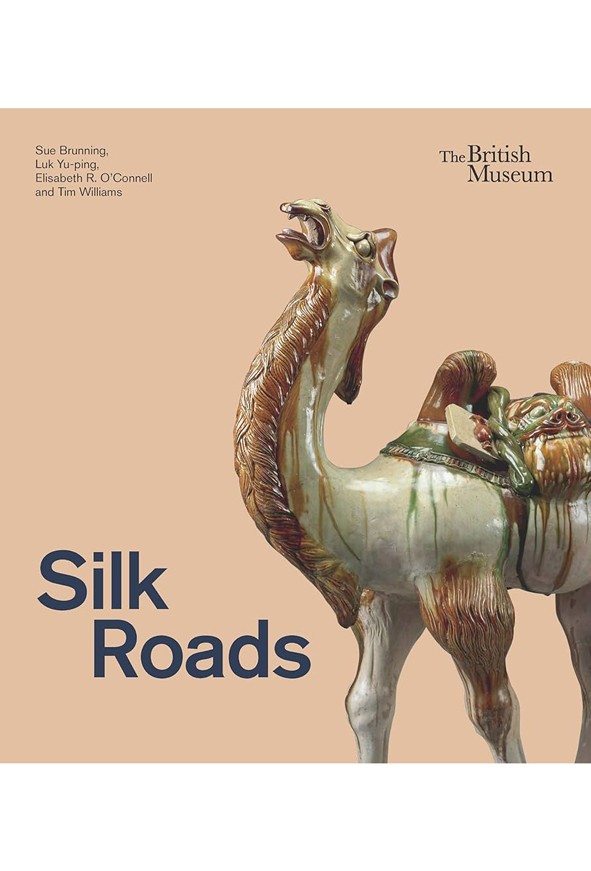

Silk Roads

Sue Brunning et al. British Museum Press (2024)

The first object discussed in this lavishly illustrated British Museum exhibition book reveals the far-ranging, mysterious nature of the Silk Roads. It is a Buddha figure, excavated in Sweden from a site dated to around ad 800, and probably created in Pakistan two centuries earlier. No one knows how it reached Europe or its significance there. As the authors — three of them exhibition curators — admit, it is “impossible to capture the full extent and complexity of the Silk Roads in a single publication”— even by limiting their time frame to only five centuries.

The Last Human Job

Allison Pugh Princeton Univ. Press (2024)

A century ago, notes sociologist Allison Pugh, people doing their food shopping gave lists to shop workers, who retrieved the goods then haggled over the prices. The process epitomized what she terms connective labour, which involves “an emotional understanding with another person to create the outcomes we think are important”. A healthy society requires more connective labour, not more automation, she argues in her engaging study, which observes and interviews physicians, teachers, chaplains, hairdressers and more.

Becoming Earth

Ferris Jabr Random House (2024)

According to science journalist Ferris Jabr, his intriguing book about Earth — divided into three sections on rock, water and air — is “an exploration of how life has transformed the planet, a meditation on what it means to say that Earth itself is alive”. If this definition sounds similar to the Gaia hypothesis by chemist James Lovelock and biologist Lynn Margulis, that is welcome to Jabr, who admires Lovelock as a thinker and personality. He also recognizes how the 1970s hypothesis, which evolved over decades, still divides scientists.

Into the Clear Blue Sky

Rob Jackson Scribner (2024)

Earth scientist Rob Jackson chairs the Global Carbon Project, which works to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions and improve air and water quality. His book begins hopefully on a visit to Rome, where Vatican Museums conservators discuss the “breathtaking” restoration of the blue sky in Michelangelo’s fresco The Last Judgement, damaged by centuries of grime and visitors’ exhalations. But he ends on a deeply pessimistic note on a research boat in Amazonia, which is suffering from both floods and fires: the “Hellocene”.

THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW (October 12, 2024): The latest issue features ‘The Heart of the Matter’

These terrifying tales by the likes of Stephen King and Shirley Jackson are more than good reads: They’ll freak you out, too.

The memoir, which will cover his time in prison and Russia’s move toward autocracy, will be published by Crown, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

The South Korean author, best known for “The Vegetarian,” is the first writer from her country to receive the prestigious award.

Literary Review – October 2, 2024: The latest issue features Richard Vinen on Churchill; @wendymoore99 on Marie Curie; Ritchie Robertson on Augustus the Strong; @robinsimonbaj on British art and @tomlamont on James Salter

‘It’s not a bad life for the leaders of the British bourgeoisie! There’s plenty for them to protect in their capitalist system!’ So wrote Ivan Maisky, the Soviet ambassador in London, after his first visit to Winston Churchill’s country house at Chartwell in Kent. He described the house thus: ‘A wonderful place! Eighty-four acres of land … all clothed in a truly English dark-blue haze.’

Frederick Augustus (1670–1733), elector of Saxony and king of Poland, owed his sobriquet ‘the Strong’ to such feats as crushing a tin plate in his hand (mentioned by Rilke in the ‘Fifth Duino Elegy’) and to his vigorous sex life. Contemporaries credited him with fathering 354 illegitimate children; Tim Blanning soberly reduces the number to eight. This biography is concerned not with court gossip, however, but with Augustus’s political career and cultural achievements. Blanning celebrates Augustus as the virtual creator of the once-magnificent city of Dresden, where the kings of Saxony resided, and hence, surprisingly, as ‘a great artist, arguably the greatest of his age’.

nature Magazine Science Book Reviews – September 27, 2024: Andrew Robinson reviews five of the best science picks.

Environomics

By Dharshini David

Why should an orangutan care what toothpaste a person uses, asks economist Dharshini David, in her appealing book about how human lifestyle choices affect the planet. Answer: some toothpastes use palm oil to create foam, whereas others don’t, and palm-oil production requires the clearing of tropical forests, eliminating the habitats of creatures such as orangutans. “Nearly every issue that affects the environment comes down, in some way, to what someone, somewhere, is doing to make (or save) money,” she writes.

Mapmatics

By Paulina Rowińska

From world maps designed by geographer Gerardus Mercator for marine navigation in the sixteenth century to online maps created by Google for self-driving cars in the twenty-first century, maps rely on mathematics. “While different on the surface, the jobs of a mathematician and a cartographer are surprisingly similar,” writes mathematician Paulina Rowińska in her engaging and original history of ‘mapmatics’. Indeed, maps not only depend on mathematics but have also inspired many mathematical breakthroughs.

The Arts and Computational Culture

By Tula Giannini & Jonathan P. Bowen

This substantial, topical collection on the arts and computing, edited by information scientist Tula Giannini and computer scientist Jonathan Bowen, begins with polymath Leonardo da Vinci’s blending of art and science and ends with a survey of modern art exhibitions that involve computing. As the editors write, “facilitated by computing, artificial intelligence, machine learning, algorithms, and simulated human senses, the arts are expanding their horizons”. Perhaps AI will eventually stand also for Artistic Imagination?

Women in the Valley of the Kings

By Kathleen Sheppard

Discussions of Egyptologists tend to focus on men — for example, Howard Carter, who excavated Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922. Yet, women played an important part in Egyptology, as historian Kathleen Sheppard describes. She begins in the 1870s with Marianne Brocklehurst and Amelia Edwards’s A Thousand Miles up the Nile, and ends with Caroline Ransom Williams’s death in 1952. Lacking permission to find artefacts, these women “acquired, organized and maintained” the world’s largest collections of Egyptian objects.

This Ordinary Stardust

By Alan Townsend

Alan Townsend, dean of the college of forestry and conservation at the University of Montana in Missoula, calls himself a biogeochemist. This field can teach us, he remarks, about cornfields, fertilizers, lake colours, sea life and even planetary warming. It can also “nurture the soul”. He learnt this truth when both his beloved wife and four-year-old daughter fell ill with brain cancer, and only the child recovered. His moving memoir describes how scientific wonder rescued him from appalling grief and suicidal thoughts.

Foreign Policy (September 20, 2024): The Mediterranean was the backdrop for much of FP’s summer reading. For the first installment of our new column about international fiction, we travel to two very different settings along this vast sea: Muammar al-Qaddafi’s Libya and modern Sicily. Plus, we highlight the buzziest releases in international fiction this month.

Hisham Matar (Random House, 416 pp., $28.99, January 2024)

Hisham Matar’s latest novel, recently longlisted for the 2024 Booker Prize, is about friendship and exile. Matar, a Libyan American writer based in London, was raised in a family of anti-Qaddafi dissidents and has made the tyrant’s maniacal rule the subject of most of his work.

In My Friends, Matar follows protagonist and narrator Khaled from his school days in Benghazi to the period following Qaddafi’s overthrow in 2011. After attending a 1984 anti-Qaddafi demonstration in London and landing on the dictator’s hit list, Khaled is forced to upend his quiet life as a university student in Edinburgh and start over in the British capital. (The real-life protest, where officials at the Libyan Embassy shot several protesters and killed a police officer, led Libya and Britain to sever ties.)

Khaled develops strong friendships with two fellow Libyans in London, Hosam and Mustafa. Unlike Khaled, both are unwavering in their political convictions. Although Khaled is opposed to Qaddafi’s regime, he is also aware of the costs—and futility—of speaking out. That Khaled’s criticism of Qaddafi’s Libya never leaves the private, rhetorical sphere is a point of contention between him and his friends. Ultimately, Hosam and Mustafa return to Libya in 2011 to join the militias fighting Qaddafi; Khaled remains in Britain, deeply insecure about his inaction.

Khaled’s decision to attend the 1984 protest was one he made hesitantly, so it is all the more shocking that his first brush with activism fundamentally altered the course of his life. Khaled’s father, an academic who resigned himself to a mid-level career under Qaddafi to avoid repression, had taught his son that it is “almost always best to leave things be.”

At its core, My Friends is a debate over whether, in the face of repression, such silence is a form of self-preservation or cowardice. This tension exists between the book’s main characters—the friends—as well as within Khaled’s own head. While Khaled’s exile led him to make great friends, his time in London is equally a painful experience of solitude. With Libyan phone lines tapped and mail pilfered by the regime, he has had to uphold a decades-long lie to his family about why he can no longer return home—all because he attended a single protest.

An author with an agenda might have sought to portray Hosam and Mustafa as valiant fighters whose sacrifices are rewarded, opposite Khaled, who prefers comfort to confrontation. But Libyan history does not follow a morally righteous narrative arc. At the end of the book, Libya becomes enveloped in a new crisis, and each friend seeks to find his place within it.—Allison Meakem

Jo Hamya (Pantheon, 240 pp., $26, August 2024)

The Mediterranean is a time-honored stage for the psychosocial dramas of the elite. From British novelist John Fowles’s 1965 masterpiece, The Magus, to the entire Mamma Mia! franchise, fictional foreigners have long flocked to Greek and Italian isles to escape from—and, more often, confront—their heartbreaks and pathologies and familial squabbles. Often left out of these tales are the locals.

The Hypocrite by British author Jo Hamya at first seems like more of the same. It takes place over the course of one staging of a play about a summer that Sophia, the young playwright, once spent in Sicily’s Aeolian Islands with her father, a famous novelist whose work has aged poorly. It’s a smooth and often witty portrait of the upper-middle-class London art scene, written in the streamlined Rachel Cusk-esque register that defines much contemporary literary fiction.

Yet The Hypocrite also attempts to do something more. Although Sophia’s family dramas make up the bulk of the narrative, Hamya eventually shifts her focus to the family’s housekeeper in Sicily. She recalls that Sophia “was demanding in the worst way an English tourist could be.” Sophia didn’t try to learn even a little Italian. She and her father, the housekeeper thinks, were “lazy, messy people” who never bothered “to make her job easier with the simplest of acts.”

Hamya’s novel is part of the recent trend of examining who, historically, has been omitted in traditional narratives, especially ones set in locales that are under-resourced, exoticized, and deeply reliant on tourism. (Sicilians are European, yes, but they also live in one of Italy’s poorest regions.) In this regard, the novel is closer in spirit to HBO’s The White Lotus, the much-lauded send-up of the rich at a luxury resort chain (first in Hawaii, then in Sicily, and soon in Thailand), than many of its other predecessors.

Hamya does not dwell, however, on this upstairs-downstairs dynamic. Rather than skewering the careless interlopers, she aims for a bit more nuance, attending—if only fleetingly—to both the narrower interests of her protagonists and the invisible hands that helped set the stage for them that summer.—Chloe Hadavas

THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW (September 15, 2024): The latest issue features ‘Making Art and Selling Out’ = In Danny Senna’s fleet, funny novel “Colored Television”, a struggling writer in a mixed-race family is seduced by the taste of luxury….

Three new books examine debt’s fraught politics and history.

The Supreme Court justice has been drawn to American history and books about the “challenges and triumphs” of raising a neurodiverse child. She shares that and more in a memoir, “Lovely One.”

THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW (April 20, 2024): The latest issue features….

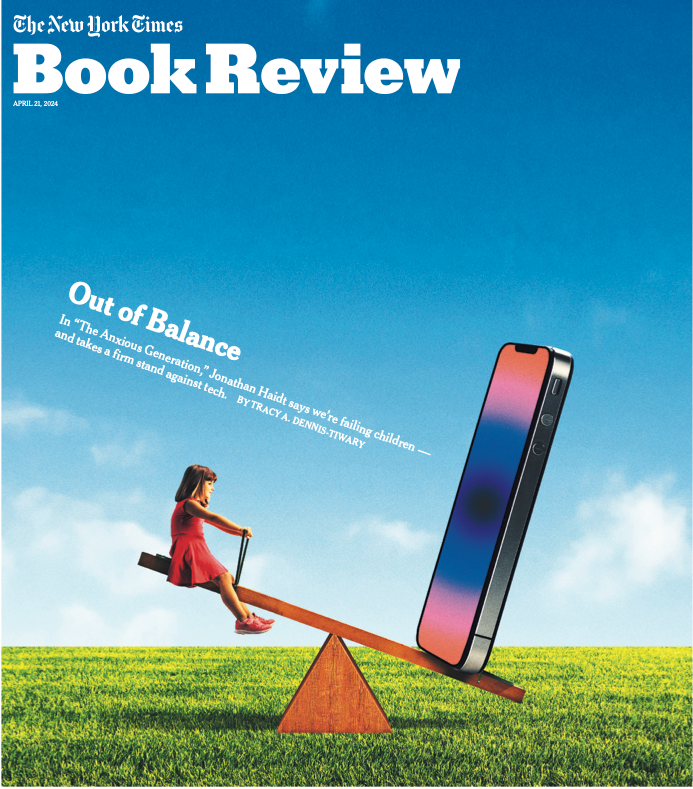

In “The Anxious Generation,” Jonathan Haidt says we’re failing children — and takes a firm stand against tech.

By Tracy Dennis-Tiwary

THE ANXIOUS GENERATION: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness, by Jonathan Haidt

Inside the book conservation lab at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

By Molly Young

Not every workplace features a guillotine. At a book conservation lab tucked beneath the first floor of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the office guillotine might as well be a water cooler or a file cabinet for all that it fazes the staff. “We have a lot of violent equipment,” said Mindell Dubansky, who heads the Sherman Fairchild Center for Book Conservation.

In “Muse of Fire,” Michael Korda depicts the lives and passions of the soldier poets whose verse provided a view into the carnage of World War I.