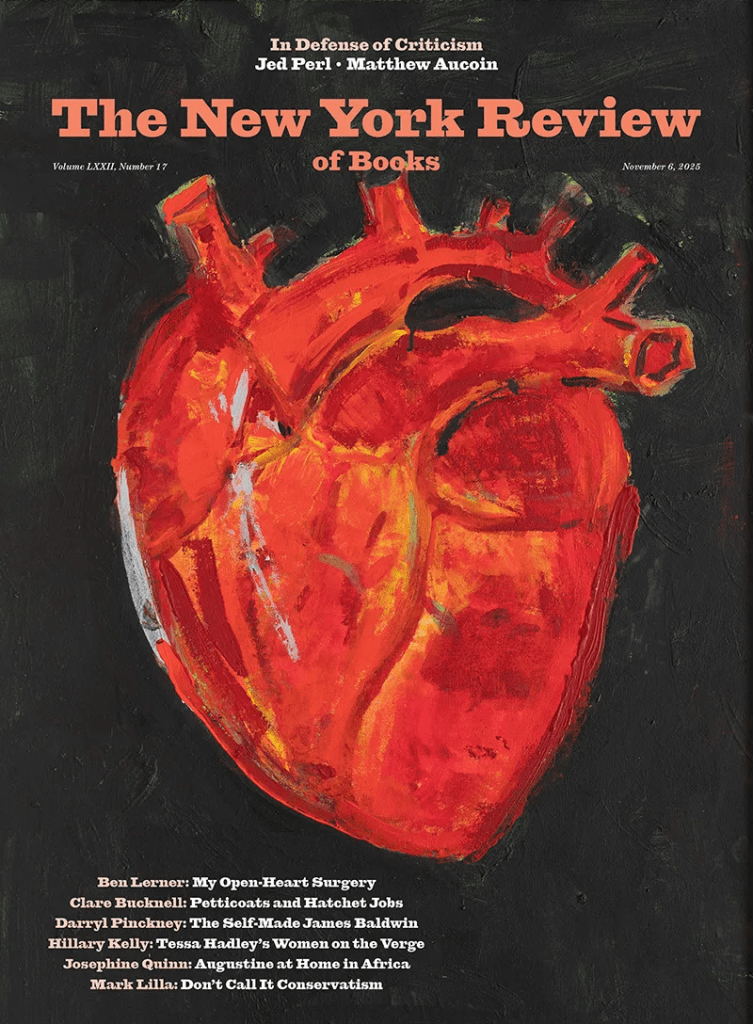

THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS: The latest issue features Anne Enright on a day in Jeffrey Epstein’s life, Jacob Weisberg on the Great Crash, Ingrid D. Rowland on Giorgia Meloni alla fresco, Robert G. Kaiser on Citizen Bezos, Marilynne Robinson on two-party tyranny, Catherine Nicholson on the first diarist, Nathan Thrall on a lost Hebrew classic about the Nakba, David Cole on the fate of affirmative action, Aaron Matz on satire, Orville Schell on Chiang Kai-shek, Mark Lilla on a nineteenth-century protofascist, a poem by Patricia Lockwood, and much more.

‘The Devil Himself’

Sifting through a single day of Jeffrey Epstein’s emails reveals a surprising amount about the man and his many enablers.

Tick, Tick…Boom!

Andrew Ross Sorkin’s history of the 1929 stock market crash reminds us that financial bubbles are inevitable—and that another one may be about to pop.

1929: Inside the Greatest Crash in Wall Street History—and How It Shattered a Nation by Andrew Ross Sorkin

Post Mortem

When Jeff Bezos bought The Washington Post in 2013 and promised to find inventive ways to make journalism profitable in the digital age, he seemed like a godsend. He wasn’t.

Rembrandt’s DNA

The Leiden Collection—one of the largest private collections of Dutch art in the world—was conceived as a “lending library for Old Masters,” animated by the humanist spirit found in Rembrandt’s paintings.

Art and Life in Rembrandt’s Time: Masterpieces from the Leiden Collection – an exhibition at the H’ART Museum, Amsterdam, April 9–August 24, 2025, and the Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, Florida, October 25, 2025—March 29, 2026

The Leiden Collection Online Catalogue, Fourth Edition edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Elizabeth Nogrady