As populations age, the number of younger people entering the workforce is shrinking – and that’s a big problem for “pay as you go” state pension schemes where employees fund the pensions of an expanding cohort of retired people.

Confusingly, a new poll of six European nations reveals how most voters can see this problem and realise their state pensions will soon become unaffordable. But at the same time, they also believe state pensions are too low, and are unwilling to support reforms to them.

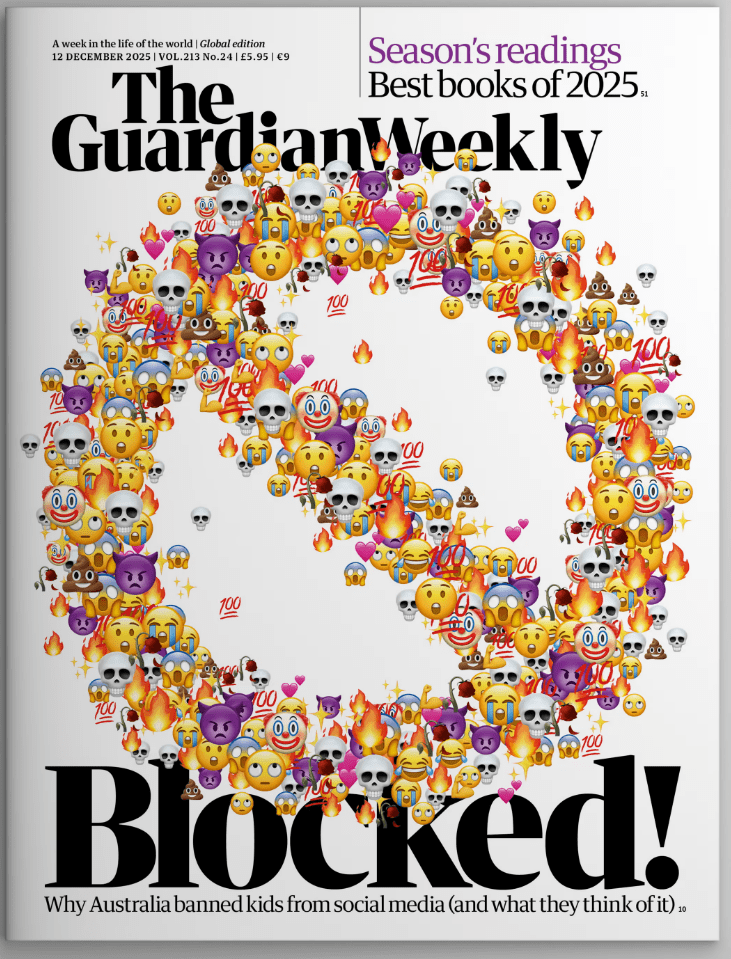

Where do governments under increasing pressure from populists go from here? For our first big story of 2026, the Guardian’s Europe correspondent, Jon Henley, reports on a ticking timebomb for the continent’s social contract.

Spotlight | The prospects for peace in Ukraine in 2026

As Russia inches forward on the battlefield and – despite Donald Trump’s optimism – peace talks remain deadlocked, Kyiv’s best hopes of progress may be on the economic and political fronts, writes Dan Sabbagh

Science | How great a threat is AI to the climate?

The datacentres behind artificial intelligence are polluting the natural world – and some experts fear the exponential rise in demand could derail the shift to a clean economy. Ajit Niranjan reports

Feature | Returning to the West Bank after two decades

The former Guardian correspondent Ewen MacAskill used to report frequently from the Palestinian Territory. Twenty years after his last visit, he went back – and was shocked by how much worse it is today

Opinion | Need cheering up after a terrible year? I have just the story for you

A single act of kindness reminded columnist Martin Kettle that, despite so much evidence to the contrary, the better angels of our nature are not necessarily doomed

Culture | The Brit boom

Whether it’s Charli xcx or chicken shops, UK culture is having a moment. Can it be future-proofed from the diluting forces of globalisation? Rachel Aroesti investigates