Excerpts from The Revolutionary Seymour, By Steven Heller:

Seymour’s art was postmodern long before the term was coined. Yet it was resolutely modern in its rejection of the nostalgic and romantic representation, as in the acolytes of Norman Rockwell, that had been popular in mainstream advertising magazines at the time. Instead of prosaic or melodramatic tableau, Seymour emphasized clever concept. What makes the very best of his art so arresting, and so identifiable, is the tenacity of his ideas—simple, complex, rational, and even absurd ideas.

Seymour’s art was postmodern long before the term was coined. Yet it was resolutely modern in its rejection of the nostalgic and romantic representation, as in the acolytes of Norman Rockwell, that had been popular in mainstream advertising magazines at the time. Instead of prosaic or melodramatic tableau, Seymour emphasized clever concept. What makes the very best of his art so arresting, and so identifiable, is the tenacity of his ideas—simple, complex, rational, and even absurd ideas.

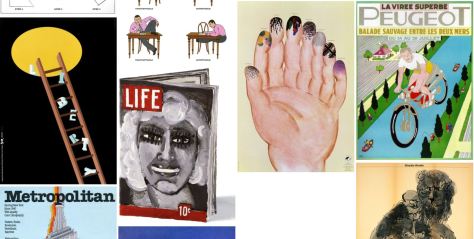

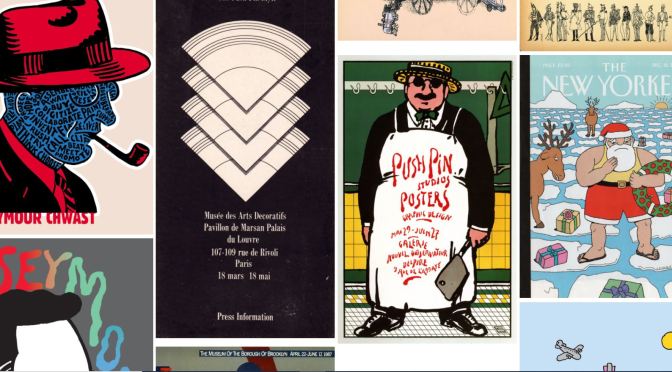

The illustrations for magazines, posters, advertisements, book jackets, record covers, product packages, and children’s books that he created after founding Push Pin Studios with Milton Glaser and Edward Sorel in 1954 directly influenced two generations (statistical fact) and indirectly inspired another two (educated conjecture) of international illustrators and designers to explore an eclectic range of stylistic an conceptual methods.

To read more: http://seymourchwastarchive.com/about/seymour/

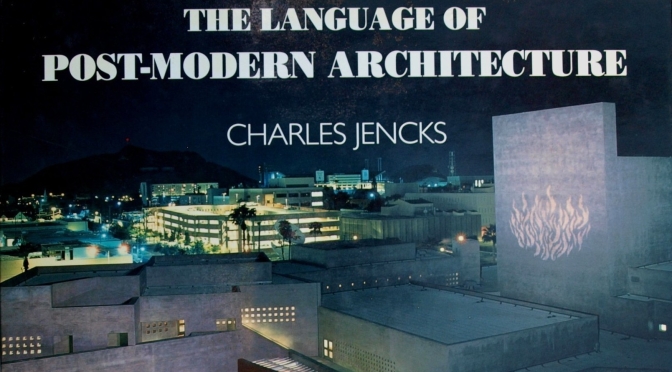

Jencks’s book grew out of his PhD thesis, supervised by Reyner Banham at the University of London in the late 1960s, and paved the way for his later, more explicitly polemical The Language of Post-Modern Architecture (1977). In this bestselling book, Jencks set out his stall for a pluralist architecture that rejected what he saw as modernism’s reductive ‘univalent’ approach, swapping it for a symbolically rich and historically engaged ‘multivalent’ postmodernism. For good or bad it became the defining book of its era, an unabashed rejection of mainstream modernism that ushered in a new architectural style.

Jencks’s book grew out of his PhD thesis, supervised by Reyner Banham at the University of London in the late 1960s, and paved the way for his later, more explicitly polemical The Language of Post-Modern Architecture (1977). In this bestselling book, Jencks set out his stall for a pluralist architecture that rejected what he saw as modernism’s reductive ‘univalent’ approach, swapping it for a symbolically rich and historically engaged ‘multivalent’ postmodernism. For good or bad it became the defining book of its era, an unabashed rejection of mainstream modernism that ushered in a new architectural style. Modern Movements in Architecture (1973) by Charles Jencks was one of the first books on architecture I read, a birthday present given to me the summer before I started my degree. In some ways, it spoiled things: I thought all architecture books would be that much fun. Modern Movements in Architecture is a complex and sophisticated history, but it wears its learning lightly. It relates architecture to a wider cultural discourse and it is unafraid to be critical, even of some architects, such as Mies van der Rohe, who were previously considered to be above criticism.

Modern Movements in Architecture (1973) by Charles Jencks was one of the first books on architecture I read, a birthday present given to me the summer before I started my degree. In some ways, it spoiled things: I thought all architecture books would be that much fun. Modern Movements in Architecture is a complex and sophisticated history, but it wears its learning lightly. It relates architecture to a wider cultural discourse and it is unafraid to be critical, even of some architects, such as Mies van der Rohe, who were previously considered to be above criticism.