From a New Scientist online review:

The prevailing narrative of “battling cancer” in Western society has its own issues, with its discourse of personal triumph that values individual responsibility and determination. But the alternative – to lie outright – might seem inconceivable, particularly to those accustomed to the norms of Western culture. It is, however, a common practice in China, rooted in the belief that telling a person about their diagnosis can make their condition deteriorate quicker.

The plot line of The Farewell is familiar to me. Like Billi’s Nai Nai, my aunt was diagnosed with metatastic lung cancer. Nobody in the family told her – nor did the doctors when she later underwent surgery to remove a tumour. The last time I saw her was in north-eastern China a few years ago. Her once-plump figure had shrunk to a wiry frame. She was in her early 70s, in good spirits, but a far cry from the feisty matriarch who used to dominate conversations.

The plot line of The Farewell is familiar to me. Like Billi’s Nai Nai, my aunt was diagnosed with metatastic lung cancer. Nobody in the family told her – nor did the doctors when she later underwent surgery to remove a tumour. The last time I saw her was in north-eastern China a few years ago. Her once-plump figure had shrunk to a wiry frame. She was in her early 70s, in good spirits, but a far cry from the feisty matriarch who used to dominate conversations.

The Farewell is a heartfelt film, punctuated by moments of unexpected – and unexpectedly uplifting – humour. In a darkly comical scene in a printing shop, Nai Nai’s younger sister demands that the results of a medical report be doctored to edit out references to cancerous nodules and replaced with the nebulous term “benign shadows”.

“It’s a way of life that’s gone and I don’t think it’s a bad state that it’s gone. But realistically it must’ve been livable on a level by pretty well everyone involved or it wouldn’t have gone on for a thousand years.”

“It’s a way of life that’s gone and I don’t think it’s a bad state that it’s gone. But realistically it must’ve been livable on a level by pretty well everyone involved or it wouldn’t have gone on for a thousand years.”

No Time to Die, as Bond 25 is called, will be out on April 8, 2020 in the U.S. and April 3 in the UK.

No Time to Die, as Bond 25 is called, will be out on April 8, 2020 in the U.S. and April 3 in the UK.

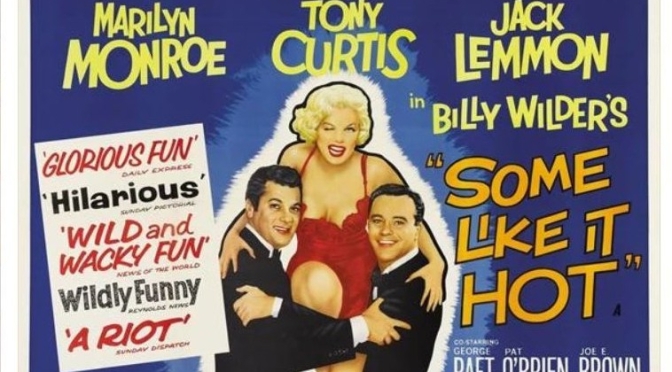

Faced with the question of why Some Like It Hot has topped BBC Culture’s poll of the best ever big-screen comedies, it’s tempting to say something similar. Wilder’s glittering masterpiece doesn’t just use the handsomest kid in town (and a terrific actor, to boot), but its most radiant sex symbol, Marilyn Monroe, and one of its most dexterous comedians, Jack Lemmon. It also has a bevy of bathing beauties, a crowd of sinister mafiosi, a glamorous seaside setting in the roaring ‘20s, and a sizzling selection of songs.

Faced with the question of why Some Like It Hot has topped BBC Culture’s poll of the best ever big-screen comedies, it’s tempting to say something similar. Wilder’s glittering masterpiece doesn’t just use the handsomest kid in town (and a terrific actor, to boot), but its most radiant sex symbol, Marilyn Monroe, and one of its most dexterous comedians, Jack Lemmon. It also has a bevy of bathing beauties, a crowd of sinister mafiosi, a glamorous seaside setting in the roaring ‘20s, and a sizzling selection of songs.

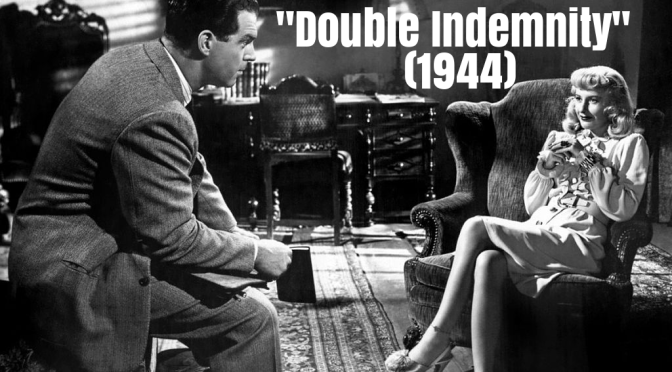

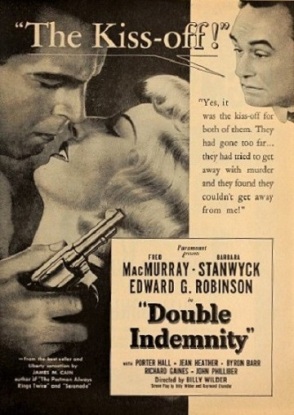

Seventy-five years ago, “Double Indemnity” opened in theaters across America. It was an instant hit, and remains to this day a staple offering of revival houses and on cable TV and streaming video. Yet little journalistic notice has been taken of the birthday of Billy Wilder’s first great screen drama, a homicidal thriller that nonetheless had—and has—something truly unsettling to say about the dark crosscurrents of middle-class American life.

Seventy-five years ago, “Double Indemnity” opened in theaters across America. It was an instant hit, and remains to this day a staple offering of revival houses and on cable TV and streaming video. Yet little journalistic notice has been taken of the birthday of Billy Wilder’s first great screen drama, a homicidal thriller that nonetheless had—and has—something truly unsettling to say about the dark crosscurrents of middle-class American life.