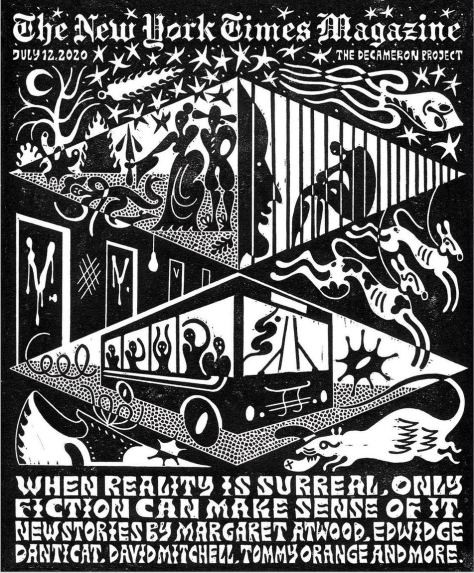

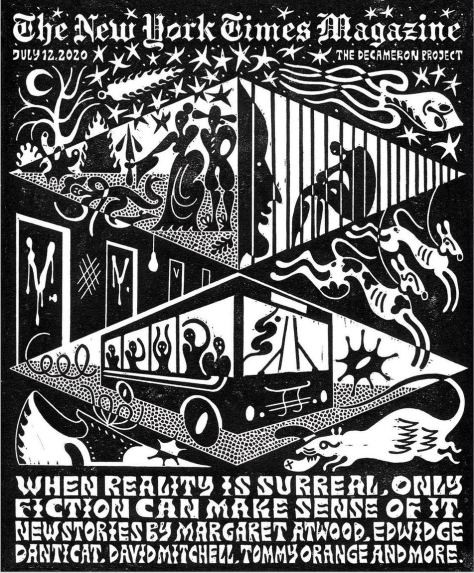

AS THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC SWEPT THE WORLD, WE ASKED 29 AUTHORS TO WRITE NEW SHORT STORIES INSPIRED BY THE MOMENT. WE WERE INSPIRED BY GIOVANNI BOCCACCIO’S “THE DECAMERON,” WRITTEN AS THE PLAGUE RAVAGED FLORENCE IN THE 14TH CENTURY.

AS THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC SWEPT THE WORLD, WE ASKED 29 AUTHORS TO WRITE NEW SHORT STORIES INSPIRED BY THE MOMENT. WE WERE INSPIRED BY GIOVANNI BOCCACCIO’S “THE DECAMERON,” WRITTEN AS THE PLAGUE RAVAGED FLORENCE IN THE 14TH CENTURY.

| INSIDE THE ISSUE |

| FEATURES | Eric Fischl interviewed by Thomas Marks; Linda Wolk-Simon on the life and legacy of Raphael; Joanne Pillsbury on the art of the Olmecs; Samuel Reilly on private restitution of colonial-era artefacts; Christopher Turner on shopfronts and gallery facades; Josie Thaddeus-Johns on John Cage’s mushrooms |

| REVIEWS | Isabelle Kent on Murillo at the National Gallery of Ireland; Tom Stammers on the British fashion for French interiors; James Lingwood on Stephen Shore’s photographs; Robert O’Byrne on The Buildings of Ireland |

| MARKET | Melanie Gerlis on art businesses after lockdown; a preview of Parcours des Mondes; and the latest art market columns from Susan Moore and Emma Crichton-Miller |

| PLUS | Rowan Moore and Tamsin Dillon on the future of public spaces; Susan Moore on the mysterious ‘Barbus Müller’ sculptures; William Aslet on Palladio’s monument to the plague in Venice; Robert O’Byrne on Apollo and the Second World War |

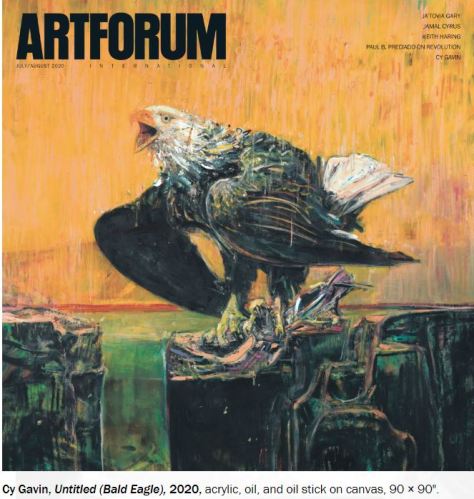

I WAS A COMPETITIVE BIRDER in high school. My family drove all around the countryside, so I spent a lot of time in the car, and I had to keep myself busy and project my brain somewhere. I would bring sketchbooks and field guides that I got from the library. I had started an Envirothon team at my school, to compete in the national decathlon pitting nerdy teens against each other in their knowledge of soil surveys, forestry, wildlife, and aquatic ecology.

I was the birding specialist. I learned more than two hundred birdsongs and birdcalls from CDs and from the field. I participated in other competitions where I would win binoculars and forty-pound bags of birdseed. I didn’t even have a bird feeder—I’d just become obsessed.

Unlike bird-watchers, birders often rely first on auditory cues to identify a species. You immediately know so much about the bird—its seasonal plumage, age, sex, if it’s making a courtship call or a warning call—from listening. The second thing you cultivate is an idea of where the call is coming from, so you can zero in on it. You develop a spatial awareness, so even with your eyes closed the woods become a vivid visual experience.

A steward of the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania once took me out in a canoe to this extremely remote location to see a bald eagle’s ten-foot nest. Eagle populations had been devastated by the use of DDT. At the time, all nest sites had to be reported to the government and kept secret. In 2007, the bald eagle was removed from the list of threatened and endangered species, and ever since, I would catch myself looking out for them whenever I’d pass a lake or river. Where I work, in upstate New York, I see bald eagles all the time. Two years ago, I found a nesting pair in Poughkeepsie near a waste-treatment plant on the Hudson River. I just spent time watching and drawing them. It was very unglamorous. They eat garbage. They’re like pigeons. The river freezes in the winter, and I have a vivid memory of watching this wet, bedraggled eagle on a chunk of ice.

Cy Gavin is an American artist that lives and works in New York. Gavin often incorporates unusual materials in his paintings such as tattoo ink, pink sand, diamonds, staples, Bermudiana seeds, and cremains. Gavin also works in sculpture, performance and video.