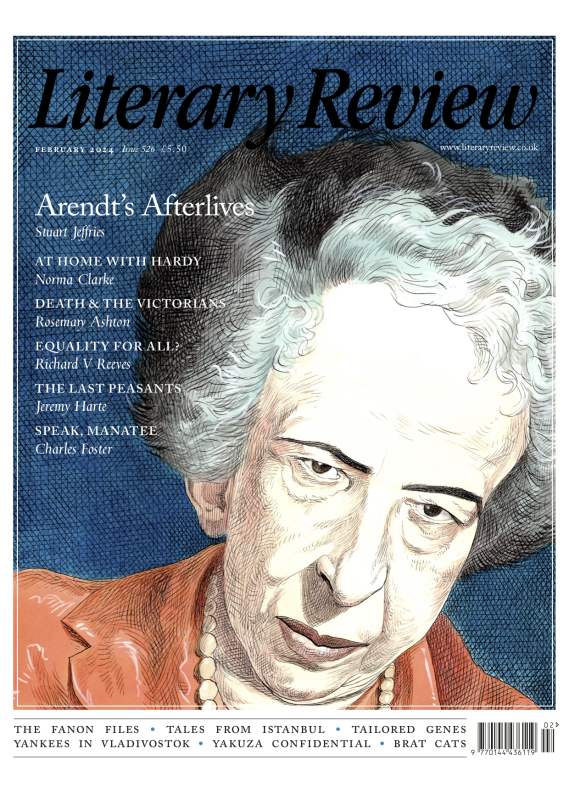

Literary Review – February 2, 2024: The latest issue features ‘We Are Free to Change the World: Hannah Arendt’s Lessons in Love and Disobedience’;

Anatomist of Evil

By STUART JEFFRIES

We Are Free to Change the World: Hannah Arendt’s Lessons in Love and Disobedience By Lyndsey Stonebridge

When Hannah Arendt looked at the man wearing an ill-fitting suit in the bulletproof dock inside a Jerusalem courtroom in 1961, she saw something different from everybody else. The prosecution, writes Lyndsey Stonebridge, ‘saw an ancient crime in modern garb, and portrayed Eichmann as the latest monster in the long history of anti-Semitism who had simply used novel methods to take hatred for Jews to a new level’. Arendt thought otherwise.

Sue Bridehead Revisited

By Norma Clarke

Hardy Women: Mother, Sisters, Wives, Muses By Paula Byrne

The title of Paula Byrne’s Hardy Women is a pun on Thomas Hardy’s name and a gesture to the enthusiasm that greeted Hardy’s fictional women. Bathsheba Everdene in Far from the Madding Crowd, Tess Durbeyfield in Tess of the d’Urbervilles and Sue Bridehead in Jude the Obscure were new kinds of women, and Hardy’s fame, which was immense and began with the publication of Far from the Madding Crowd, rested to a large extent on the heroines he created. One young reader wrote to him of Tess, ‘I wonder at your complete understanding of a woman’s soul.’ Hardy’s discontented wife Emma wondered at it too. She observed, ‘He understands only the women he invents – the others not at all.’