nature Magazine Science Book Reviews – October 14, 2024: Andrew Robinson reviews five of the best science picks.

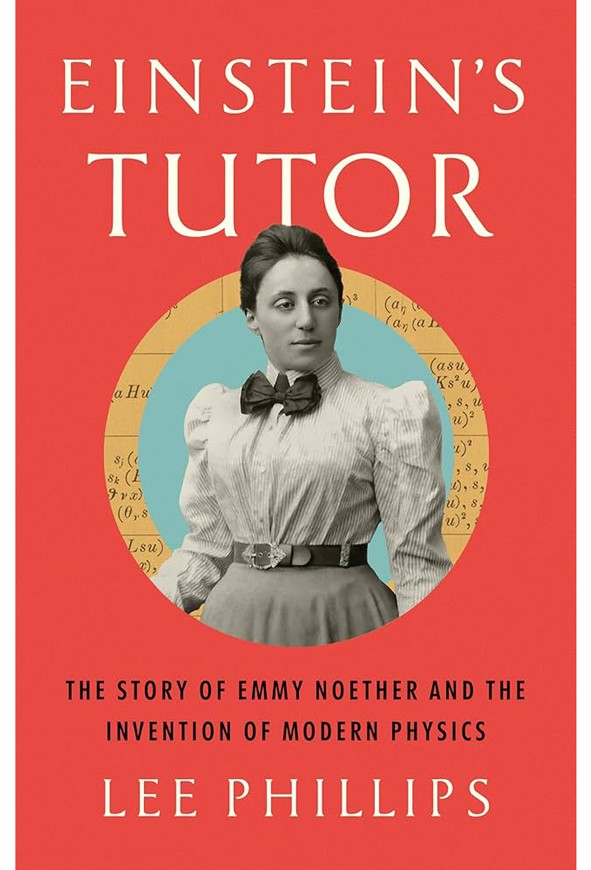

Einstein’s Tutor

Lee Phillips PublicAffairs (2024)

Major studies of Albert Einstein’s work contain minimal, if any, reference to the role of German mathematician Emmy Noether. Yet, she was crucial in resolving a paradox in general relativity through her theorem connecting symmetry and energy-conservation laws, published in 1918. When Noether died in 1935, Einstein called her “the most significant creative mathematical genius thus far produced since the higher education of women began”. In this book about her for the general reader, physicist Lee Phillips brings Noether alive.

Silk Roads

Sue Brunning et al. British Museum Press (2024)

The first object discussed in this lavishly illustrated British Museum exhibition book reveals the far-ranging, mysterious nature of the Silk Roads. It is a Buddha figure, excavated in Sweden from a site dated to around ad 800, and probably created in Pakistan two centuries earlier. No one knows how it reached Europe or its significance there. As the authors — three of them exhibition curators — admit, it is “impossible to capture the full extent and complexity of the Silk Roads in a single publication”— even by limiting their time frame to only five centuries.

The Last Human Job

Allison Pugh Princeton Univ. Press (2024)

A century ago, notes sociologist Allison Pugh, people doing their food shopping gave lists to shop workers, who retrieved the goods then haggled over the prices. The process epitomized what she terms connective labour, which involves “an emotional understanding with another person to create the outcomes we think are important”. A healthy society requires more connective labour, not more automation, she argues in her engaging study, which observes and interviews physicians, teachers, chaplains, hairdressers and more.

Becoming Earth

Ferris Jabr Random House (2024)

According to science journalist Ferris Jabr, his intriguing book about Earth — divided into three sections on rock, water and air — is “an exploration of how life has transformed the planet, a meditation on what it means to say that Earth itself is alive”. If this definition sounds similar to the Gaia hypothesis by chemist James Lovelock and biologist Lynn Margulis, that is welcome to Jabr, who admires Lovelock as a thinker and personality. He also recognizes how the 1970s hypothesis, which evolved over decades, still divides scientists.

Into the Clear Blue Sky

Rob Jackson Scribner (2024)

Earth scientist Rob Jackson chairs the Global Carbon Project, which works to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions and improve air and water quality. His book begins hopefully on a visit to Rome, where Vatican Museums conservators discuss the “breathtaking” restoration of the blue sky in Michelangelo’s fresco The Last Judgement, damaged by centuries of grime and visitors’ exhalations. But he ends on a deeply pessimistic note on a research boat in Amazonia, which is suffering from both floods and fires: the “Hellocene”.