THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW – JUNE 18, 2023: Stephen King reviews of S. A. Cosby’s blistering new Southern gothic, “All the Sinners Bleed,” which graces our cover this week. Also featured are John Vaillant’s chillingly prescient book about a 2016 Canadian wildfire; a history that pieces together a botany expedition in the Grand Canyon some 85 years ago; and the spiky, percussive, heavy-metal-infused novel “Gone to the Wolves.”

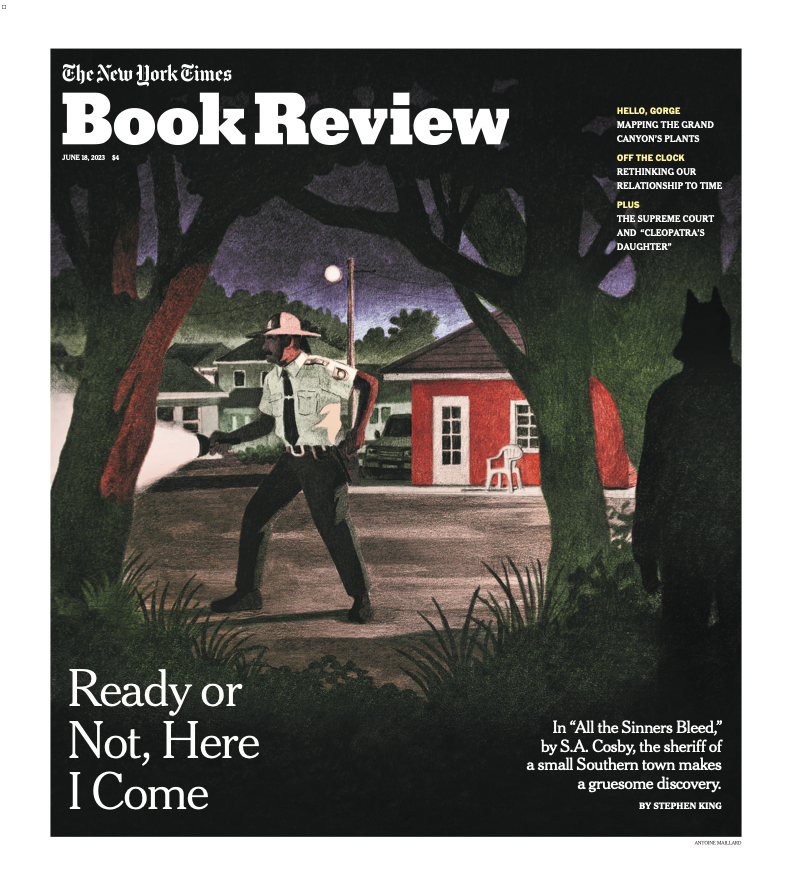

In This Thriller, the Psycho Killers Have a Southern Drawl

Stephen King reviews S.A. Cosby’s latest novel, “All the Sinners Bleed.”

Titus Crown is an ex-F.B.I. agent who gets a sheriff’s job, almost by accident, in a rural Virginia community. He’s Black. Mr. Spearman teaches geography and wears a coat of many countries on Earth Day. He’s white. Given the name of the town and county where these two live — Charon — one can expect bad things to happen, and they certainly do. As in S.A. Cosby’s previous two novels, “Blacktop Wasteland” and “Razorblade Tears,” the body count is high and the action pretty much nonstop.

They Overcame Hazards — and Doubters — to Make Botanical History

In Melissa Sevigny’s “Brave the Wild River,” we meet the two scientists who explored unknown terrain — and broke barriers.

Let’s start this story on a sun-blistered evening in August 1938. A small band of adventurers had just concluded a 43-day journey from Utah to Nevada — although perhaps “journey” is too tame a description for a trip that had required weeks of small wooden boats tumbling down more than 600 miles of rock-strewn rivers. The goal was twofold. First, to simply survive. And then, to chart the plants building homes along the serrated walls of the Grand Canyon.