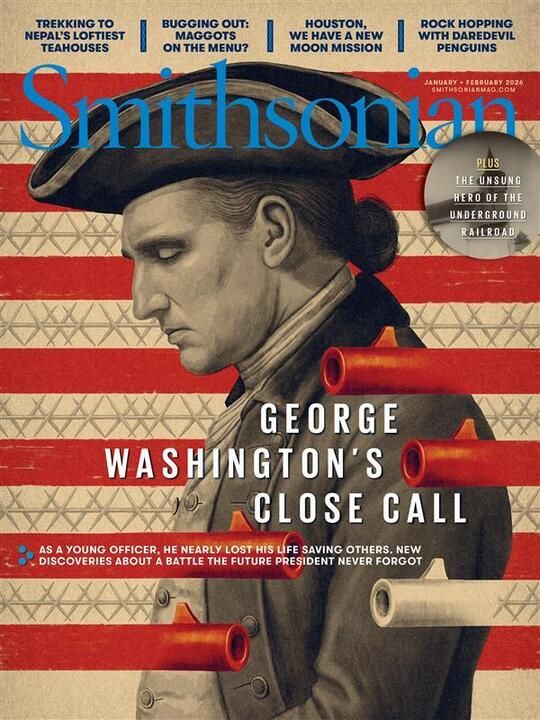

Samuel Green Freed Himself and Others From Slavery. Then He Was Imprisoned Over Owning a Book

After buying his own liberty, the Marylander covertly assisted conductors on the Underground Railroad, including Harriet Tubman. But his possession of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” turned him into an abolitionist hero

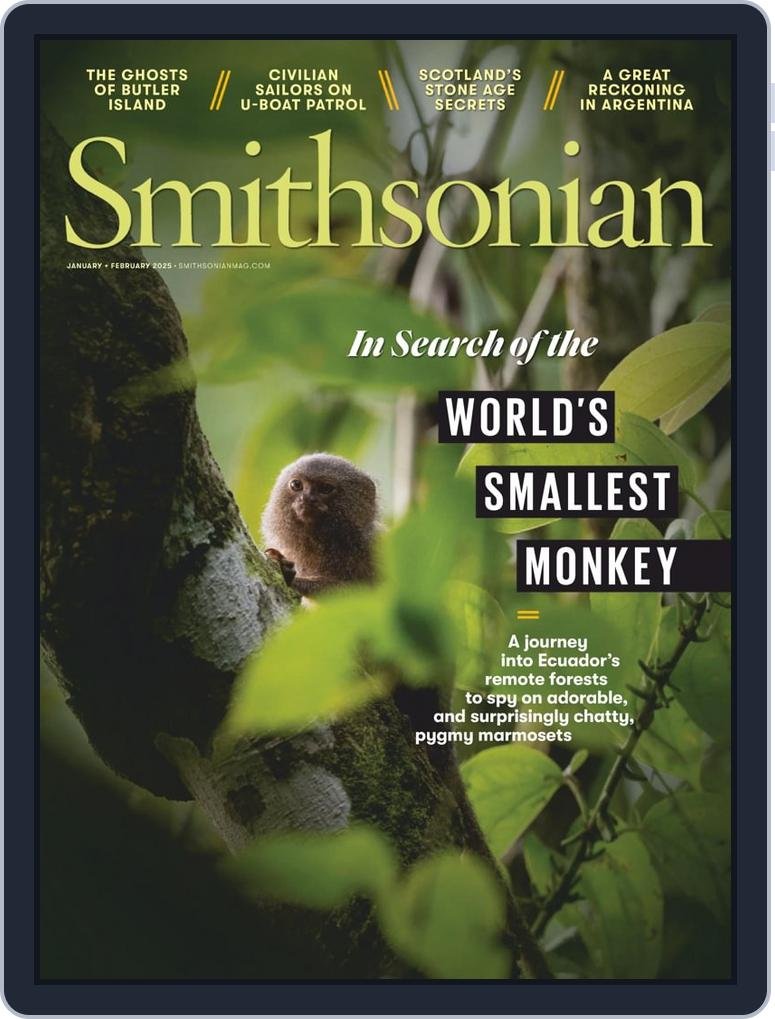

Maggots Are an Incredibly Efficient Source of Protein, Which May Make Them the Next Superfood for Humans

Inexpensive to raise and insatiably hungry for trash, black soldier fly larvae are already on the menu for livestock, pets and, maybe soon, people

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/79/64/7964e23e-abcf-409b-af0d-df56a2216c06/julaug2024_g10_berenike.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c3/b8/c3b8af90-5ec2-4793-8f88-d577c27f9d18/julaug2024_k18_ikedikegalveston.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c4/a2/c4a27834-0cf0-4f9b-821b-28314beed28d/julaug2024_c02_prologue.jpg)