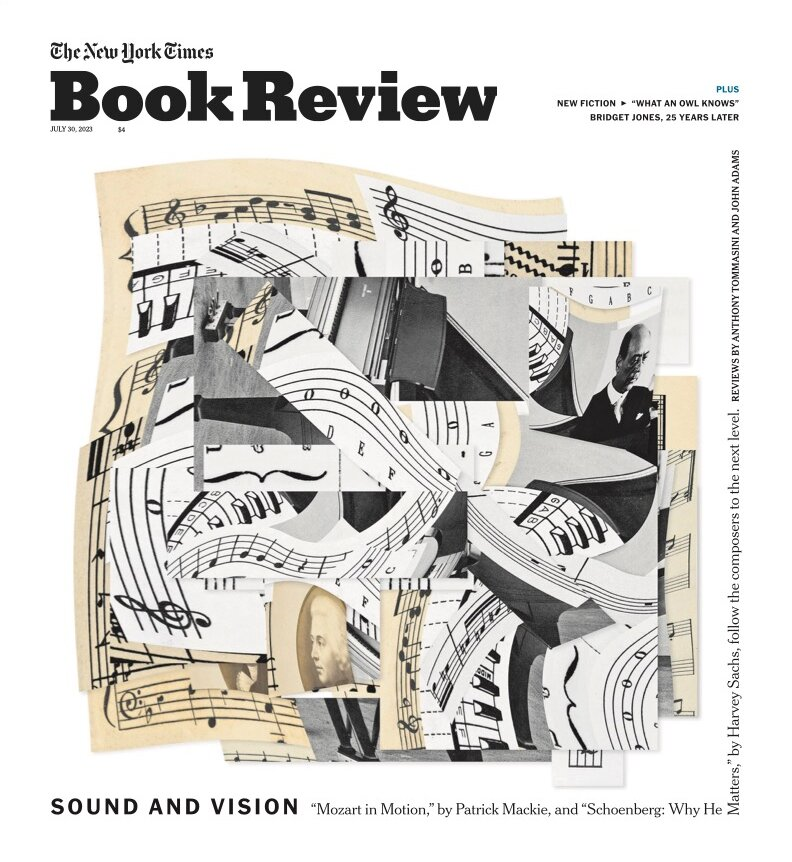

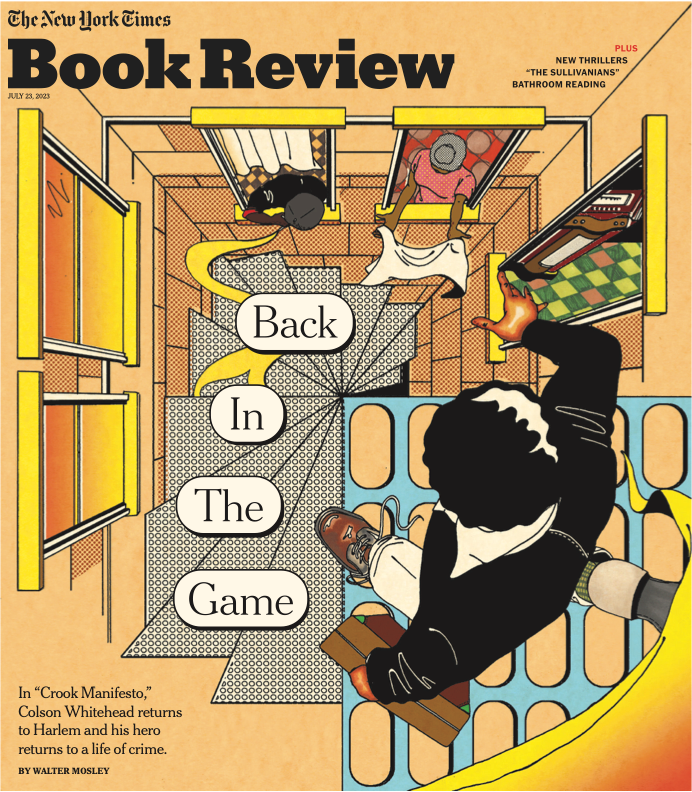

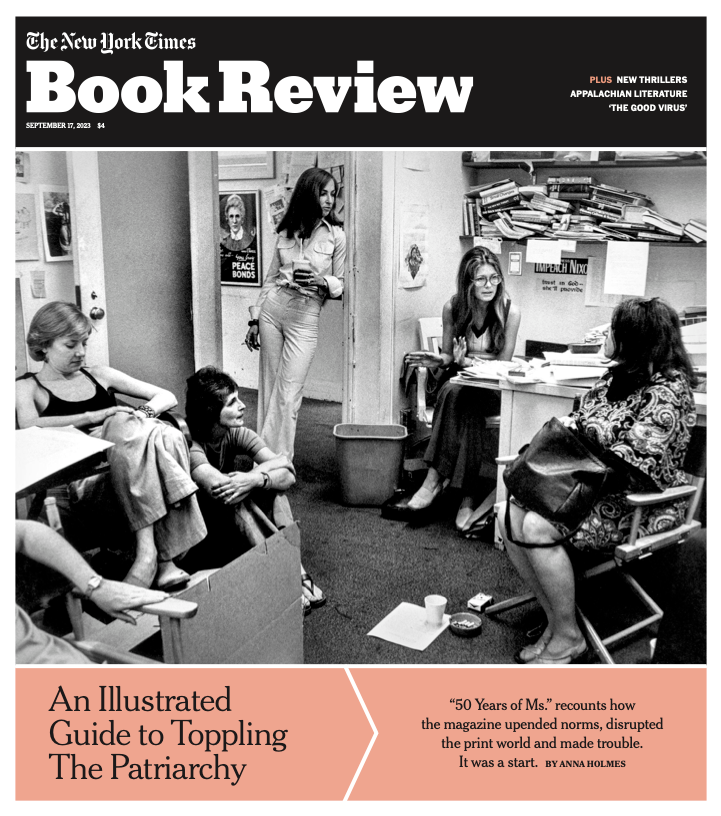

THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW (September 17, 2023): The new issue features An Illustrated Guide to Toppling the Patriarchy, New Thrillers, Appalachian Literature, The Good Virus, and more…

An Illustrated Guide to Toppling the Patriarchy

In its first half-century, Ms. magazine upended norms, disrupted the print world and made trouble. It was a start.

By Anna Holmes

50 YEARS OF MS.: The Best of the Pathfinding Magazine That Ignited a Revolution, edited by Katherine Spillar and the editors of Ms.

I had my first conscious interaction with Ms. magazine as a small child when I read — or rather, had read to me — a story-poem called “Black Is Brown Is Tan.”

Part of the magazine’s delightful kids’ section, “Black Is Brown Is Tan” is about a mixed-race family not unlike my own who go about their daily routines like any other Americans. Though I was young, I remember the illustrations, by Emily Arnold McCully, with acute clarity: the rosy cheeks of the white dad, the short Afro and hoop earrings of the Black mom, and, perhaps most important, the sense of safety and warmth that permeated every page. In our house, where my mother was careful about the messaging of the media and toys we consumed, the “Stories for Free Children” section was always welcome. As for the magazine they appeared in? Well, it was canon.

A Rich, Capacious Family Saga, Bookended by Tragedy

In Diana Evans’s new novel, “A House for Alice,” a woman who immigrated to Britain for marriage must decide whether or not to return to her country of origin after her husband dies.

By Tiphanie Yanique

A HOUSE FOR ALICE, by Diana Evans

Houses in Diana Evans’s new novel, “A House for Alice,” are a metaphor for family. They’re filled with rooms for sleeping, lovemaking, fighting; contain corridors that lead to areas of welcome and comfort; shelter spaces that hold secrets. And like a house, a family can be burned to nothing and rebuilt anew.